Robotics is shaping up to be the next transformative technology of our time, says legal expert Ryan Calo, who argues in a new paper that we need laws to deal with the rise of robotics and artificial intelligence.

“Technology has not stood still. The same private institutions that developed the Internet, from the armed forces to search engines, have initiated a significant shift toward robotics and artificial intelligence,” writes Calo, assistant professor in the School of Law at University of Washington.

“Courts that struggled for the proper metaphor to apply to the internet will struggle anew with robotics.”

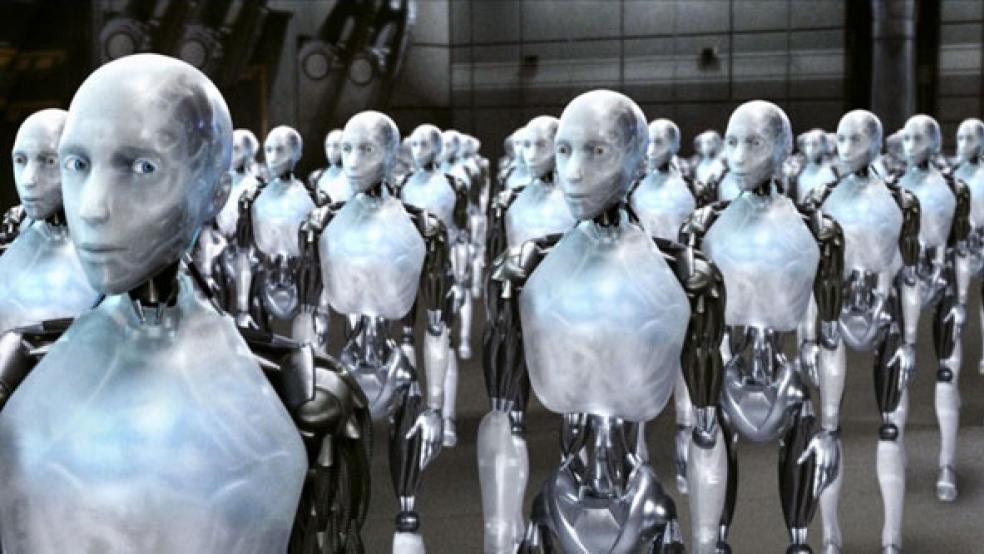

Terminators and Hal

Though mention of robotics and artificial intelligence can prompt images of unstoppable Terminators and mutinous HAL 9000 computers, Calo dismisses such drama early on.

“And yet,” he says, “the widespread distribution of robotics in society will, like the internet, create deep social, cultural, economic, and of course legal tensions” long before any such sci-fi-style future.

Robotics is essentially different than the Internet and so will raise different legal issues, Calo says.

“Robotics combines, for the first time, the promiscuity of data with the capacity to do physical harm. Robotic systems accomplish tasks in ways that cannot be anticipated in advance, and robots increasingly blur the line between person and instrument.”

Easterbrook and Doctorow

But does that mean robotics and artificial intelligence need different treatment under the law, or different laws entirely, than the technologies of which they are made, such as computers?

In the paper, published in the California Law Review, Calo relates an anecdote about Chicago judge and law professor Frank Easterbrook, who in 1996 famously likened research in Internet law to studying “the law of the horse.” Easterbrook felt any single approach is doomed to “be shallow and to miss unifying principles.”

Calo also quotes science fiction writer Cory Doctorow, who wrote that he could not think of a legal principle applicable to robots that would not also be usefully applied to the computer, and vice versa.

“I disagreed with Easterbrook then and I disagree with Doctorow now,” Calo writes. “Robotics has a different set of essential qualities than the Internet, which animate a new set of legal puzzles.”

‘An Idea Whose Time Has Come’

Calo’s conclusion is, in a sense, a follow-up to his 2014 call for the creation of a federal robotics commission: Robotics and artificial intelligence have essentially different qualities than the law has yet faced, he says.

“So I join a chorus of voices, from Bill Gates to the White House, to assume that robotics represents an idea whose time has come.

“The qualities, and the experiences they generate, occasion a distinct catalog of legal and policy issues that sometimes do, and sometimes do not, echo the central questions of contemporary cyberlaw.

“Cyberlaw will have to engage, to a far greater degree, with the prospect of data causing physical harm, and to the line between speech and action. Rather than think of how code controls people; cyberlaw will think of what people can do to control code.”

This article was published originally in Futurity by Peter Kelley of the University of Washington