The fiscal impact of the Republican plan to repeal the Affordable Care Act may not be clear at the federal level until the Congressional Budget Office completes its review of the proposed legislation, but an analysis of the plan by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities finds that one thing is pretty clear: State budgets are going to get pummeled if the proposal as written becomes law.

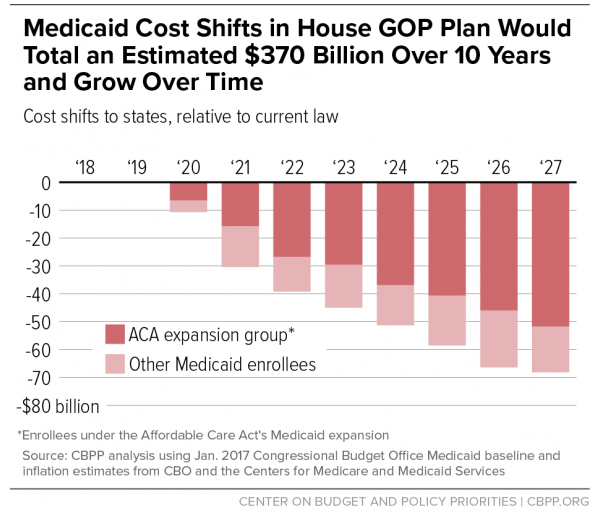

Edwin Park, CBPP’s vice president for health policy, issued an updated analysis of the plan’s proposed changes to the Medicaid program and determined that the American Health Care Act would cost states $370 billion in federal aid over ten years -- a number that would begin increasing even more sharply as time went on.

Related: Conservatives Don’t Like What They See in the Obamacare Replacement Plan

“The new House Republican health plan would shift an estimated $370 billion in Medicaid costs to states over the next ten years,” Park claims, “effectively ending the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) Medicaid expansion for 11 million people while also harming tens of millions of additional seniors, people with disabilities, and children and parents who rely on Medicaid today.”

The long-awaited replacement plan, released late Monday, would turn Medicaid into a block grant program, meaning that states would receive a fixed amount of money based on the number of people on the Medicaid rolls in a given year. The existing program is an entitlement and per-state spending is not capped.

The proposal would also effectively eliminate the Medicaid expansion under which the ACA allowed certain eligible working-age adults access to the program. The federal government previously bore 90 percent of the costs of that expansion.

However, according to Park, “Starting in 2020, states would receive only the regular federal Medicaid matching rate — on average, 57 percent of Medicaid costs, with states covering the other 43 percent — for any new enrollees under the expansion instead of the ACA’s matching rate of 90 percent. This means that expansion states would have to pay 2.8 to 5 times more in terms of their own costs.”

Related: House GOP Obamacare Replacement Plan Has Major Gaps in Cost and Coverage

People who were on the plan as of the end of 2019 would be allowed to remain, with the ACA’s original matching rate still applying, but new recipients would not. But because most people on Medicaid tend to fall off the rolls within a few years, the end result would be an ever-dwindling share of recipients were still eligible for the 90 percent match.

States would still technically be allowed to offer expanded coverage, but Park notes that “within just a few years, the overwhelming share of Medicaid expansion spending would eventually be subject to the regular matching rate. To maintain the expansion as it’s now operating in the expansion states, we estimate that these states would have to increase their share of costs by about $253 billion over ten years.”

The cap on per-patient spending would also rise more slowly than the cost of care is expected to in coming years, meaning that the block grants to states will, in effect, buy less and les coverage as time goes on.

“In response,” writes Park, “states would have to contribute much more of their own funding or, far likelier, substantially cut eligibility, benefits, and provider payments, with those cuts growing more severe each year.”