How will the block grant system proposed by Republicans affect Medicaid? A new study finds the impact would vary wildly from state to state, with some being forced to increase their annual spending on Medicaid by very large margins if they offer the same level of services that they did before the cut.

A key element of the Republican plan to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act is the devolution of responsibility for Medicaid to the states by turning the program into a per capita block grant, which limits the federal contribution to the entitlement program, which provides health insurance to the poor, elderly, and children.

Related: Medicaid Expansion Is Working for Low-Income Adults, but Can It Last?

While it’s impossible to know exactly how such a program would play out, three health care scholars at the Brookings Institution tried to simulate what a similar program would have looked like if it had been implemented in years past, for which full sets of data on Medicaid expenditures are available. The AHCA version of the plan would take effect in Fiscal 2020 and would cap spending based on each state’s per capita Medicaid patient costs in 2016. In the years after 2020, the cap would be raised in line with the Consumer Price Index for Medical Care and would take into consideration the number of people that the program covers in each state who have conditions that require unusual levels of care.

Authors Loren Adler, Matthew Fiedler, and Tim Gronniger analyzed a program in which the AHCA program was launched in 2004 with caps based on spending levels set in 2000, and modeled the impact through 2011.

What they found is a program with no winners, but a whole lot of losers.

Related: Republicans Eye Medicaid Cuts to Help Finance Their New Health Plan

That’s because the way the system is set up: If a state’s per capita spending in a given year is lower than projected, its benefits are reduced by the same amount.

In a way, the authors note, this means the program doesn’t operate as a true block grant, which is good news for the federal budget, but bad news for states that might want to try to make federal dollars go further through innovation or cost savings.

They found that by 2011, states would be spending an average 11 percent more to maintain the same level of Medicaid services that they had provided prior to the implementation of the per capita funding cap. The move would have saved the federal government $17.8 billion that year alone.

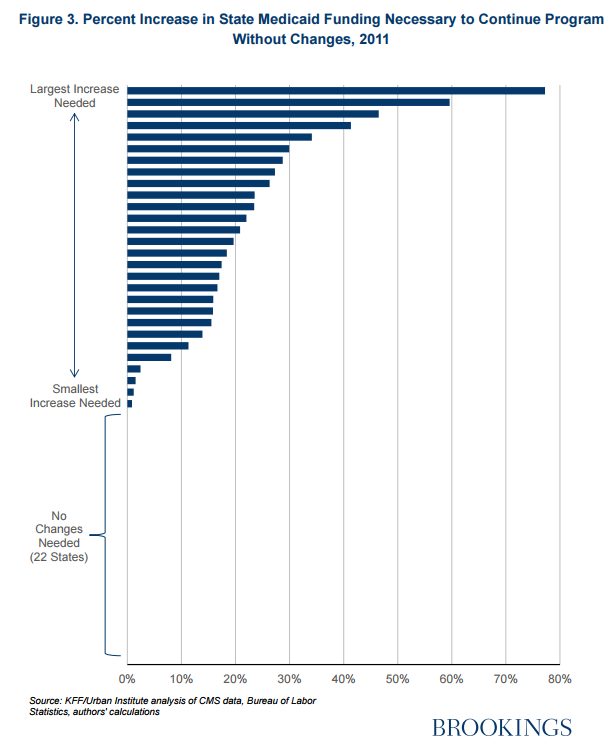

The impact varies dramatically across states. In all, 22 states would not need to contribute more than they already do to provide the same level of coverage. The other 28 would face cost increases that vary from less than 5 percent to more than 70 percent.

Related: GOP Struggles to Explain AHCA’s $880 Billion Medicaid Cuts

The increased financial burden on states, they found, could also turn out to be much greater, even with relatively small changes in the growth rate of their spending. Part of the problem, they argue, is that the Consumer Price Index for Medical Care “fails to capture many of the factors that affect overall health care spending trends.”

If the amount of money it takes to maintain services at their original level rises at a rate just one percentage point higher than in the authors’ baseline scenario, for example, the additional cost to the states in 2011 would have been $33.9 billion instead of $17.8 billion.

“The reduction in federal funding would have been smaller if spending had grown more slowly, but the magnitude of the risk to states is asymmetric due to the one-sided nature of the cap; since states can never receive more funding than under current law, they bear the full risk of higher spending growth, but capture only part of the benefit of lower spending growth,” the authors write.

Again, that’s great news for federal deficit hawks, but a huge budgetary challenge for the individual states. It’s one that many, if not most, would have to meet by reducing the services they provide through Medicaid, resulting in a system that saves money not by innovation or efficiency, but by forcing states to make painful choices.