How long will it take for oil inventories to drop to normal levels? That's the question OPEC and oil markets are grappling with before Thursday’s meeting of producer countries in Vienna.

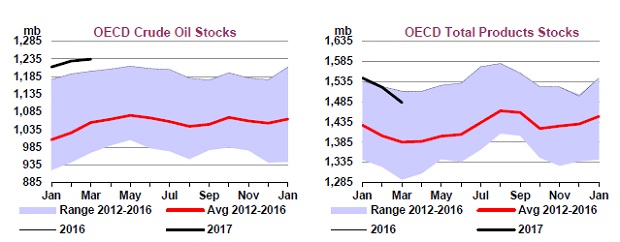

At just over 3 billion barrels, stockpiles in consumer nations are about 300 million barrels above their five-year average, little changed from levels in December when the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries and its allies agreed to cut output by about 1.8 million barrels per day (bpd).

Related: 5 Reasons Oil Prices Could Fall in 2017

The cuts were initially agreed to run during the first half of 2017. OPEC and other producers, including Russia, are now expected to agree to extend the deal on Thursday, possibly for nine more months until March.

OPEC expects inventories to return to the five-year average of 2.7 billion barrels by the end of 2017. Other experts see a longer overhang, with one institution seeing it lasting into 2019.

OPEC has repeatedly said eliminating excess stockpiles was one of its main goals but inventories remain stubbornly high. OPEC states have cut output at the wellhead, but kept exports to consumer countries high by draining their own stockpiles.

The Paris-based International Energy Agency and most other experts say global oil demand is outstripping production, so at some point stocks held in consumer states will start to drop.

But making forecasts is fraught with uncertainty because it depends on assumptions about supply and demand, the rate of exports from storage from producer nations and guesswork about storage in nations such as China, which does not disclose data.

Related: Why Oil Prices Are Tanking — and Where They’re Headed Next

The IEA releases monthly data for inventories held by the OECD group of industrialized nations, saying stockpiles of crude, oil products and other liquids at the end of March stood at 3.025 billion barrels. [EIA/M]

But IEA inventory analyst Olivier Lejeune said this only covered 50 to 60 percent of the global picture, including inventories in Western Europe, North America, Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand.

It does not track stockpiles in China and India, the world's No. 2 and No. 3 oil consumers.

The United States, an OECD member whose Energy Department releases weekly U.S. inventory data USOILC=ECI [EIA/S], is the world's biggest crude consumer.

BULLS VS BEARS

Jeffrey Currie, head of commodities research at Goldman Sachs, is among the most bullish on the rebalancing timetable.

"Do I want to be long oil? The answer is absolutely yes, because you're going into a deficit market," Currie said this month, adding the global supply deficit could be 2 million bpd by July. He did not say when inventories would return to normal.

Asset management firm AB Bernstein said in a May 16 report that OPEC cuts would "lead to accelerated inventory drawdowns in the second half of 2017, but the return to normalized inventories will ... drag into 2018."

Assuming a 1 million bpd deficit based on EIA supply and demand data, it would take 11 months to eliminate the glut, it said. "The agreement by OPEC to extend cuts into 2018 is critical," the AB Bernstein report said.

Related: Oil Prices Have Doubled Over the Past Year. Here’s Why That Won’t Last

Financial firm Natixis sees rebalancing extending into 2019. "Based on our current levels of withdrawals, expected at 280,000 bpd, that means at least two and half years, unless withdrawals increase rapidly," chief energy analyst Abhishek Deshpande said.

OPEC sees the market rebalancing by the end of 2017. "With the current rate of compliance we arrive at the five-year average by year-end, not 2018," an OPEC source told Reuters.

Algerian Energy Minister Noureddine Boutarfa echoed that timeline. He also told Reuters that extending cuts to March 2018 aimed to take into account traditionally weak demand at the start of each year.

IEA inventory data have offered little clear guidance. OECD inventories in March of 3.025 billion barrels were 32.9 million barrels lower month-on-month but were a rise of 24.1 million barrels over the quarter after a big build in January. [IEA/M]

The first quarter rise is partly seasonal, as demand falls in the period when European and U.S. refineries usually conduct maintenance. Stockpiles also grew after record OPEC export volumes to the OECD in the fourth quarter of 2016, the IEA said.

Exports from Saudi Arabia, OPEC's biggest producer, were some 600,000 bpd higher in the fourth quarter 2016 compared with the average for January and February, according to official data data the kingdom submitted to the Joint Organizations Data Initiative (JODI) www.jodidata.org/.

OPEC's cuts came into effect on Jan. 1.

The IEA has said it did not expect the inventory glut to be eliminated by the end of 2017, basing its assumption on OPEC output staying at April's levels of 31.8 million bpd with an implied drawdown of more than 700,000 bpd for the second half of the year.

OPEC and other producers must now decide how much longer they need to extend cuts to rebalance the market. OPEC ministers suggest consensus is building around the nine-month extension.

But Vienna-based JBC said nine months would not be enough. "In our current base case, we see 2018 as being strongly oversupplied, to the tune of close to 1.5 million bpd in the broader oil complex on average for the year," it said this week.

Only with an extension for the whole of 2018 and 100 percent compliance with cuts "can we envisage a market which is more or less balanced," the JBC analysts wrote.

The table lists differing views on the timetable for returning OECD inventories to the five-year average of 2.7 billion barrels: