Time after time in recent years, Republican budget writers have tried harder than Olympic gymnasts to achieve balance. In a sometimes quixotic-seeming quest to wipe out the federal deficit within 10 years, they’ve resorted to using overly optimistic economic assumptions, questionable math, “magic asterisks” and a variety of other gimmicks.

President Trump’s budget proposal for fiscal 2020, released Monday, uses a number of those tricks. It forecasts GDP growth much stronger than most independent projections, with no recession in sight even as the current economic expansion is already poised to become the longest in U.S. history. It proposes to cut some $2.7 trillion from non-defense discretionary spending, with drastic reductions to education, health care and other areas that have no chance of being adopted by Congress.

It’s notable then that, even with all that, Trump’s budget doesn’t propose to balance in the typical 10 years. Instead, the White House says it would reach balance in 15 years, by 2034.

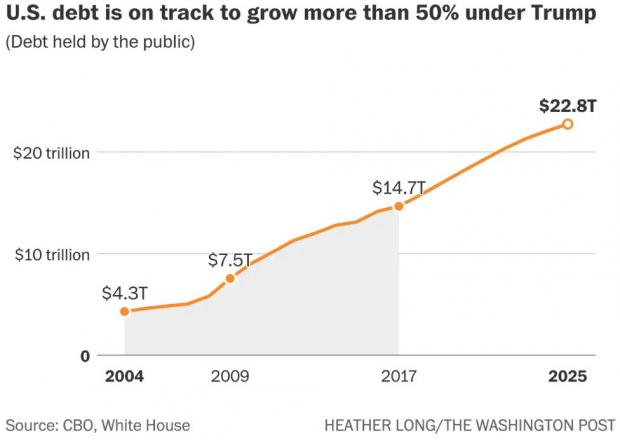

Trump’s budget claims to substantially reduce the deficit. The shortfall would go from $1.1 trillion, or 5.1 percent of GDP, in 2019 to $202 billion, or 0.6 percent of GDP, in 2029. In the interim, though, the budget projects three more years of deficits over $1 trillion. In all, the budget would borrow $7.8 trillion over the next 10 years — and using more reasonable economic assumptions, the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget finds that it would add closer to $10.5 trillion to the national debt — a far cry from Trump’s wild 2016 campaign assertion that he could eliminate the debt within eight years.

The new projections underscore just how much the debt is growing under his administration, and how hard that will be to change. “The president makes heroic assumptions about economic growth and deep cuts to domestic discretionary spending and health care, and yet he still can’t balance the budget,” Brian Riedl, a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute and former chief economist for Sen. Rob Portman (R-OH), told The Washington Post.

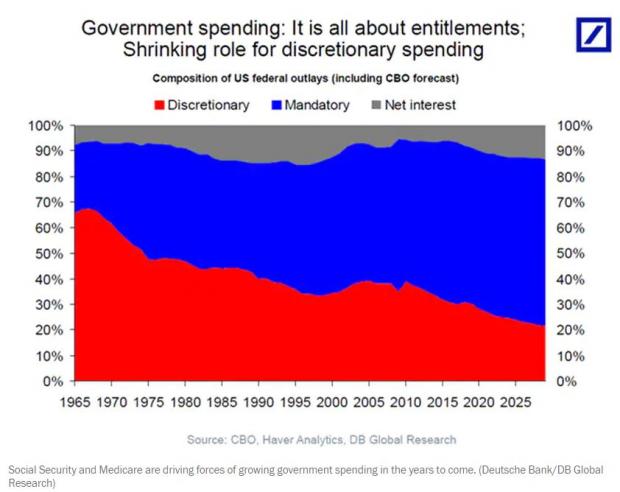

Trump’s tax cuts, and the spending deal he grudgingly signed last year, are big reasons the debt is surging. At the same time, Trump’s budget does relatively little to address the long-term drivers of the debt, namely mandatory spending on programs like Medicare and Social Security (see chart below). It does propose some cost-saving Medicare reforms, mostly through reductions in payments to providers, and it seeks an overhaul of Medicaid that could convert the program to a system of block grants to the states. The White House, meanwhile, still argues that the tax cuts will pay for themselves. “Economic policies in this budget will generate more than enough revenue to pay for the costs of the tax cut," Acting Office of Management and Budget Director Russ Vought said Monday.

There’s little evidence to support that claim, and the numbers in Trump’s budget highlight the challenges in cutting taxes and slashing spending as a path to deficit reduction. “Trump’s own budget calculations show that reducing taxes and making heavy cuts to domestic programs do not balance the budget (at least not for 15 years and not without some big assumptions),” The Washington Post’s Heather Long says.

Not that the 15-year timeframe is itself problematic. In fact, Maya MacGuineas of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget says she applauds the longer timeframe as a more achievable goal — except that the rest of Trump’s budget is littered with gimmicks and problematic assumptions. “Yes to a realistic goal, but it doesn’t amount to anything unless it coupled with realistic policies,” she said.

But there’s little appetite in Washington for deficit reduction these days. “Concern about the deficit is so woefully out of fashion that it’s hard to even imagine it coming back into fashion,” Rep. Jim Cooper (D-TN) told the Associated Press the other day. “This is as out of fashion as bell bottoms.”