Tax proposals put forth by Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders won’t generate as much revenue as their campaigns project, and in some cases would fall significantly short of estimates, according to new analyses by the Penn Wharton Budget Model, a non-partisan policy research initiative at the University of Pennsylvania.

The Biden plan: Biden calls for higher taxes on the wealthy and corporations, along with other reforms. His campaign says the proposals would raise $3.2 trillion over 10 years to fund investments in health care, climate, infrastructure and education. The Penn Wharton analysis projects that his plan would raise $600 million to $900 million less that that, or between $2.3 trillion (after economic feedback effects are factored in) and $2.6 trillion (without those macroeconomic effects). Most of the tax increases under the Biden plan would fall on the top 0.1% of income earners, raising their annual taxes by more than $1 million each and lowering their after-tax income by 14%.

Biden’s plan would have little impact on GDP, Penn Wharton finds. “The Biden proposal has two opposing effects on the macroeconomy,” the new study explains. “On one hand, reducing federal deficits increases investment, leading to greater capital accumulation and, therefore, increasing GDP. On the other hand, the increase in marginal tax rates discourage labor and savings. We project that these two effects are largely offsetting over time.”

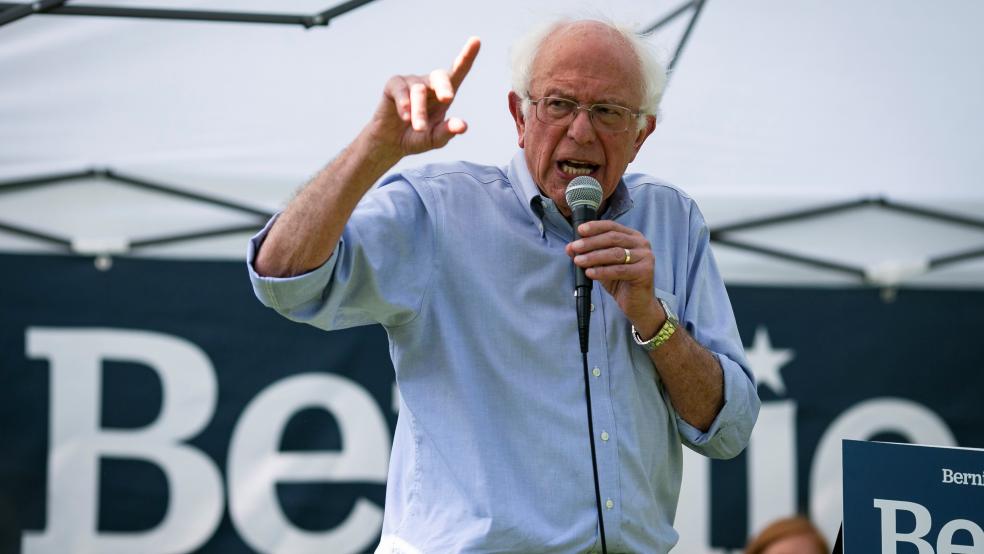

The Sanders plan: Sanders has proposed a 1% tax on net worth above $32 million for a married couple, with the tax rising until it reaches 8% on wealth over $10 billion. He also calls for higher estate taxes and the introduction of a financial transactions tax. The Sanders campaign estimates that his wealth tax would raise $4.35 trillion over a decade, but Penn Wharton projects it would fall more than $1 trillion short of that mark, raising between $2.8 trillion and $3.3 trillion over 10 years.

Projecting out to 2050, Penn Wharton says the Sanders wealth tax would reduce GDP by 1.1% and average hourly wages would fall by 1% “due to the reduction in private capital formation.”

Penn Wharton also estimates that Sanders’ plan to expand the estate tax, which would raise rates and reduce the federal exemption from its current level of about $11 million ($22 million for married couples) to $3.5 million for singles (and $7 million for couples). Sanders’ staff reportedly estimated that the tax would raise $315 billion over a decade.

Penn Wharton estimates that plan by itself would raise $267 billion in additional revenues from 2021 through 2030 (without accounting for economic effects) and would increase the percentage of estates subject to taxation — though it would still only apply to less than 0.5% of people who died in any given year.

What it all means: The results aren’t necessarily surprising. The Penn Wharton Budget Model’s earlier analysis of Sen. Elizabeth Warren’s wealth tax found that it would raise as much as $2.7 trillion in revenue over 10 years — well shy of the $3.8 trillion Warren’s camp estimated. And as we noted then, critics of the Penn Wharton model question some of its assumptions about how higher taxes affect the economy.

There are other issues with the model, as well: The latest analyses follow the Congressional Budget Office’s standard in applying revenues raised by higher taxes toward deficit reduction — even in cases where a candidate has laid out other uses for the money. Penn Wharton reportedly plans to follow up with additional analysis considering the effects of the tax plans if the revenue raised were used to fund investments that boost productivity.

More questions ahead: Still, Sanders and Elizabeth Warren have faced repeated questions about how they would pay for policy proposals such as Medicare for All and the new analyses may revive those questions, for Sanders in particular.

Biden may face some challenges, too. “Economists, including the ones who would do official analyses of any tax legislation, assume that workers ultimately pay part of the corporate income tax in the form of lower wages,” The Wall Street Journal’s Richard Rubin explains. “That means studies of proposals to raise corporate taxes do show some higher taxes—under $200 for many households in Mr. Biden’s case—for the middle class.”

In addition, the gap between the campaigns’ estimates and Penn Wharton’s nonpartisan analysis demonstrates the challenges candidates face in generating new tax revenue to fund ambitious proposals, writes Bloomberg News reporter Laura Davison:

“Overly rosy figures are fine for the campaign trail, but they wouldn’t pass muster in Congress, where any plan would be subject to an estimate from the non-partisan congressional Joint Committee on Taxation. That tally would determine how much money Democrats have to work with to implement one of their priorities, such as expanding health care coverage or infrastructure investment. … [T]o fill the gaps between their estimates and what congressional scorekeepers project, lawmakers may have to look to other, potentially less popular, sources of revenue.”