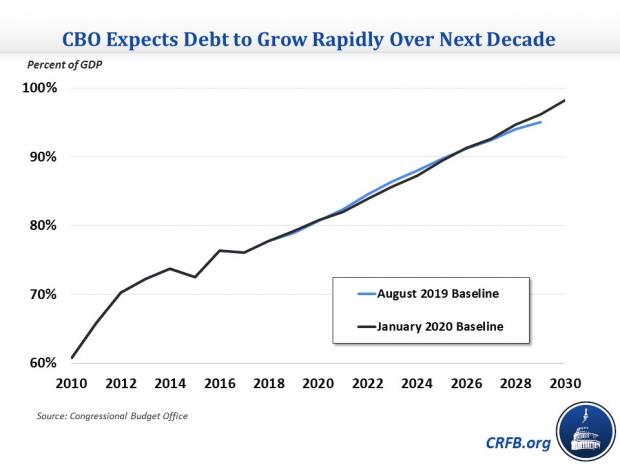

The U.S. budget deficit is expected to top $1 trillion in fiscal year 2020 and remain above that level indefinitely, lifting the national debt over the next decade to its highest level since World War II, the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office said Tuesday in its annual report on the nation’s fiscal and economic outlook.

CBO expects the deficit will rise from just over $1 trillion this year to more than $1.7 trillion in 10 years, averaging $1.3 trillion from 2021 through 2030.

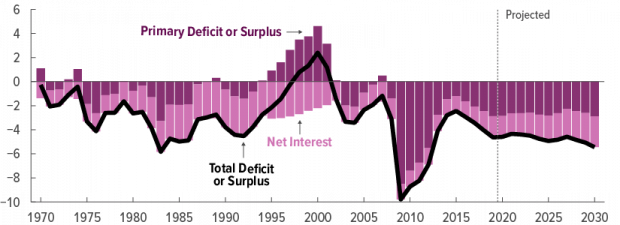

As a share of gross domestic product, the deficit is projected to rise from 4.3% next year to 5.4% in 2030.

“Not since World War II has the country seen deficits during times of low unemployment that are as large as those that we project—nor, in the past century, has it experienced large deficits for as long as we project,” CBO Director Phillip L. Swagel said in a statement accompanying the report. Swagel called the budget outlook “challenging” and “worrisome.”

As a result of the continuing deficits, the debt held by the public will rise from $17.2 trillion today, or 80% of GDP, to $31.4 trillion, or 98% of GDP, by 2030. “The long-term projections for the debt are higher than they were last year because the federal government's revenues are expected to decrease and spending is expected to increase due to legislation enacted by Congress in 2019,” the Washington Examiner’s Nihal Krishan explains.

The deficit is rising despite healthy economic growth: The economy is in its 11th year of expansion, and CBO expects gross domestic product to grow by 2.2% this year, up 0.1 percentage point from its August estimate (but shy of the Trump administration’s 3% annual target). While deficits typically shrink during periods of prolonged economic growth, the budget shortfall has surged as the result of the 2017 Republican tax law and a series of spending increases passed by Congress and signed by President Trump. And CBO expects economic growth to slow to an average annual rate of 1.7% from 2021 through 2030.

What’s widening the budget gap: More than half the current deficit is due to recent tax cuts and spending increases. Revenues are weaker than they would be without the 2017 tax overhaul, and federal spending is projected to grow faster than tax receipts, driven by increased spending for mandatory programs and interest payments on the debt, which CBO expects to rise as the government continues to borrow and interest rates eventually move higher.

Spending for Medicare is expected to rise from $835 billion this year to more than $1.7 trillion by 2030, while outlays for Social Security are forecast to climb from just under $1.1 trillion to more than $1.9 trillion. Brian Riedl, a senior fellow at the conservative Manhattan Institute, points out that the annual shortfall for Social Security and Medicare benefits payments will rise from $440 billion to nearly $1.9 trillion. “That's the ballgame,” he tweeted.

And deficits could be higher than CBO forecasts: The projections assume Congress will allow some of the 2017 tax cuts to expire as scheduled after 2025. If Congress extends the individual tax cuts, as it may be likely to do, the deficits and debt would be larger than CBO projects.

Low interest rates buy the government some time: Lower-than-expected rates have thus far served to provide some fiscal breathing room, as interest cost come in lower than projected. “Since CBO’s last budget forecast in August 2019, projected interest costs have declined by $441 billion over a decade, reflecting rates that are 0.3 percentage point below the previous estimate,” The Wall Street Journal’s Richard Rubin writes. But lawmakers have more than offset those gains, he explains: “loss of revenue from tax cuts enacted in December 2019 exceeded those savings, and CBO now projects budget deficits to be 1.3% larger than it did in August.”

Still, low rates may make addressing the short-term deficit picture less urgent. “To be sure, interest rates remain low today, suggesting that there is time to address our fiscal challenges and that fiscal policy could be used as a tool to address other challenges facing the nation, if the Congress chose to do so,” Swagel says in his statement. “But our projections also suggest that over the long term, changes in fiscal policy must be made to address the budget situation, because our debt is growing on an unsustainable path.”

But the deficits aren’t being used to invest in the future: “Trump is wasting these deficits,” Robert C. Hockett, a Cornell University professor who has advised Sens. Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren on economic policy, told The Washington Post. “It’s fine to engage in deficit spending, but Trump has used them to give tax cuts to billionaires, which does nothing to increase the well-being of the vast majority of Americans or improve the nation’s productivity.”