It's well known that the spoils of this economic recovery have benefited those at the very top. Corporate profits are at record highs. The stock market is racing toward the moon. Household net worth is moving higher by leaps and bounds.

The anecdotal evidence is all around. London and Manhattan real estate values are soaring. Ferrari dealerships are humming. Red hot IPOs for questionable business models like GoPro (NASDAQ:GPRO) and its camera-on-a-stick or inexplicable surges in shadow companies like Cynk Technology (NASDAQ:CYNK) are minting fresh fast millionaires on Wall Street.

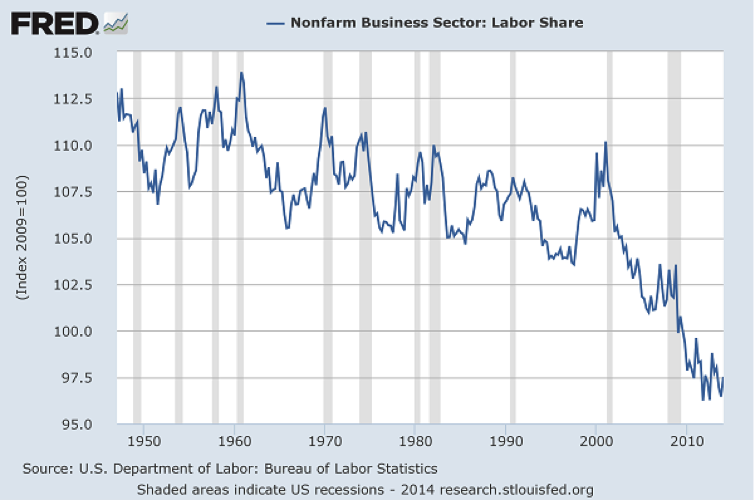

Yet regular wage-earning Americans with little or no exposure to the financial markets have been left far behind. You can see this in the way labor's share of income is plummeting in the chart below — a consequence of a long erosion of the ability of workers to demand higher wages and benefits.

Related: 10 Cities with Booming Job Growth

But this could be set to change as the job market, now six years into the recovery, finally starts to tighten.

Last week, we learned that the unemployment rate has fallen to 6.1 percent — just three-tenths of a percent away from the Congressional Budget Office’s estimate of full unemployment. Surveys by the National Federation of Independent Businesses shows a growing number of smaller firms are finding it more and more difficult to find qualified workers.

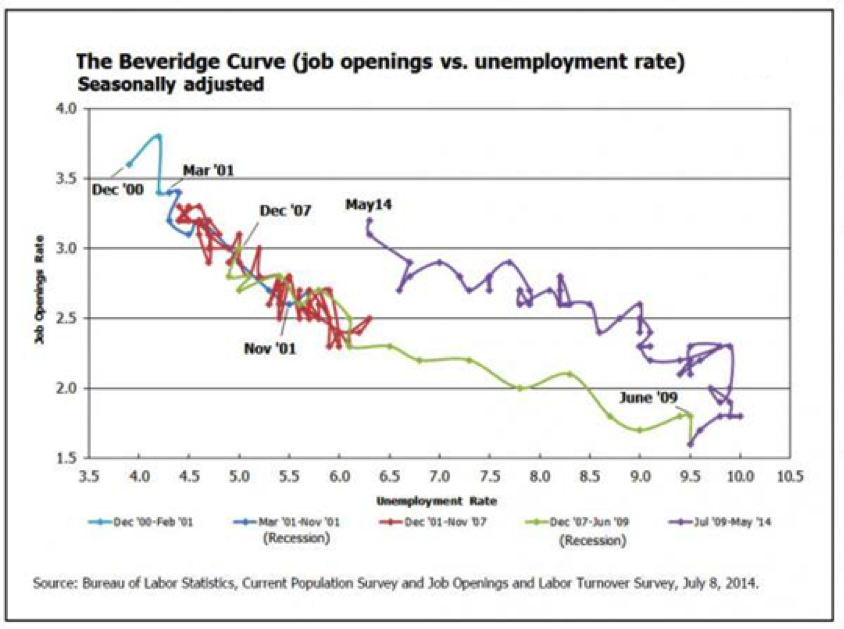

Earlier this week, the government's Job Openings and Labor Turnover survey showed that the job openings rate increased to its highest level since September 2007. The number of jobs available increased nearly 20 percent over last year and now totals 4.6 million. Private-sector job openings jumped to its highest level since June 2007 with professional and business services job openings returning to January 2006 levels.

In fact, the job market is tightening to such an extent, and apparently having difficulty matching new workers with available openings, that it’s showing signs of inefficiency. More simply, it's sort of broken.

You can see that in the chart above of the Beveridge Curve, a metric that measures how well the job market is matching the unemployed with open positions. The latest rate shows that if the job market were functioning as it had from 2000 to 2007, the unemployment rate would be near 4.5 percent, not still above 6 percent.

One translation here is that while there are still many Americans looking for work, fewer of them are qualified candidates for the nearly five million positions that are open. That means that businesses will either have to pay existing workers overtime, hire and train another worker, pay a higher wage as the competition heats up for top talent, or simply forgo potential revenue growth.

Related: No Job Loss in Most States That Raised Minimum Wage

While that's bad news for the corporate sector, which may have to suffer the indignity of seeing business profits fall to more normal levels, it could be great news for the middle class as competition for the best workers boosts wages and shifts the balance from capital to labor in a way that hasn't been seen since the Clinton administration.

You've already heard the reasons for all this. The rise of globalization. The march of technology and automation. Outsourcing. Sweatshops. The decline of the unions. A loss of American manufacturing.

There are few others that might be new, like the drop in the number of self-employed workers as regulation and patent warfare prevent moms and pops from participating in the digital/mobile revolution that's driven this business cycle.

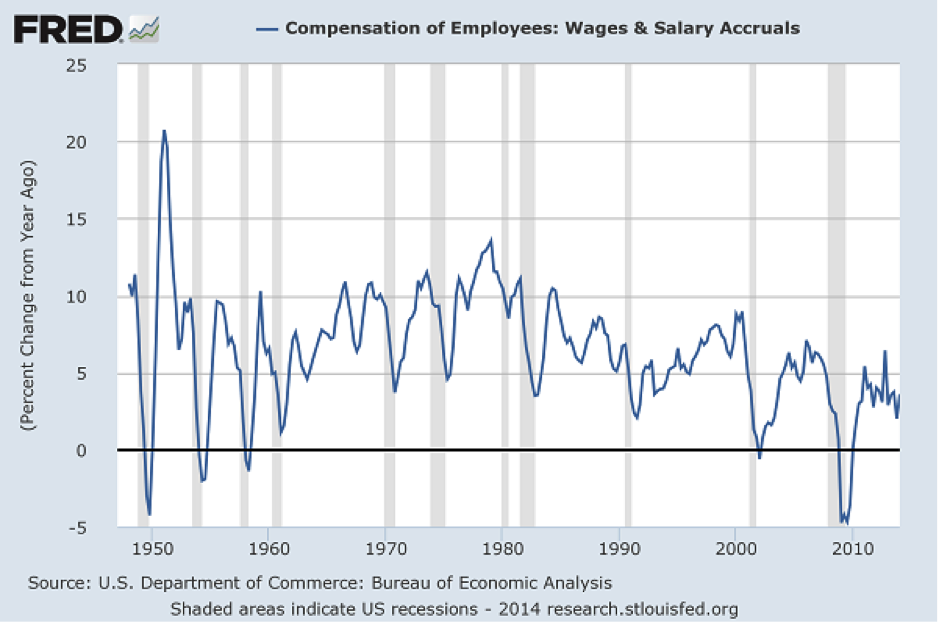

The longer that this tight and broken job market prevails, the more wage growth we'll see and the faster the mismatch between corporate profits and labor share will normalize. According to J.P. Morgan analysts, we are already seeing evidence of this in action. Between 2007 and 2011, middle-wage jobs — the backbone of the middle class — were bombed out as the growth rate of these positions stalled.

But since early 2013, a reversal has occurred, with job gains concentrated in high- and medium-wage positions. This could be a sign business are ramping up hiring plans as they realize that the available pool of good non-professional office and manufacturing workers is drying up for the first time in years.

Wage gains should follow. That's the final piece of the puzzle to fully heal this economy. It hasn't happened yet, as the chart above shows wage growth remains moribund and below the levels that prevailed in each and every economic recovery since the end of World War II.

The takeaway? In order to heal Middle America and address problems like still high household debt levels and rising inequality, we need higher wages. And in order for that to happen, the job market might need to stay broken just a little while longer.

Anthony Mirhaydari is founder of the Edge and Edge Pro investment advisory newsletters, as well as Mirhaydari Capital Management, a registered investment advisory firm.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times:

- The Costs of Obama’s Housing Mistakes Keep Piling Up

- Are Calls for Income Redistribution Based on Envy or Justice?

- The Next Financial Crisis Is Brewing Right Now, and Regulators Are Missing It