Hillary Clinton’s recent rollout of her economic policy was as close as could be expected to a summer blockbuster. She deserves high praise for the searing insight that corporate obsession with current share prices — which she terms “quarterly capitalism” — leads to misallocation of resources. That misallocation shortchanges long-term investment in critical undertakings like well-paying employment for the vast majority of households and conversion to an economy that resists and reverses climate change. Quarterly capitalism is an element of the much maligned “short-termism” of the business sector, in which today’s profits and share prices are valued, but long-term growth and stability are increasingly ignored.

But praise for Clinton fades to disappointment because her solution to quarterly capitalism, an adjustment to capital gains tax rates, holds little promise of getting the job done. What’s needed are new restrictions on Wall Street and changes to how corporations do business, territory occupied so far by Sens. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) and Elizabeth Warren (D-MA). The fact is that we have all knuckled under to Wall Street so that we have an economy that increasingly is based on finance without even asking whether Wall Street is investing in us. We can only hope that Clinton’s forthcoming policy agenda will recognize that ending income equality is only possible with real remedies to short-termism.

Related: Why Hillary Clinton’s Tax Plan to Soak Investors Won’t Work

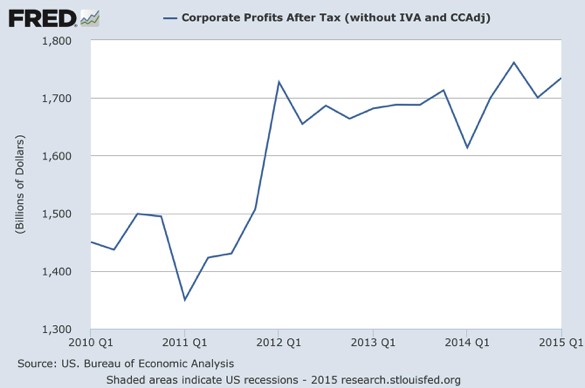

Big companies have done very well in recent years, with corporate profits increasing by almost 29 per cent since 2011. In prior times, corporate management would plow these earnings back into the business, funding growth activities like the expansion of capacity and markets or research and development. Instead, companies now distribute about 90 percent of these whopping profits to shareholders (more than $1.6 trillion in 2013 compared with about $600 billion in 2000) by paying dividends to shareholders and purchasing their own shares on the market. Such payouts support share prices even as the asset base of a company shrinks when cash is depleted by payments to shareholders rather than invested in growth.

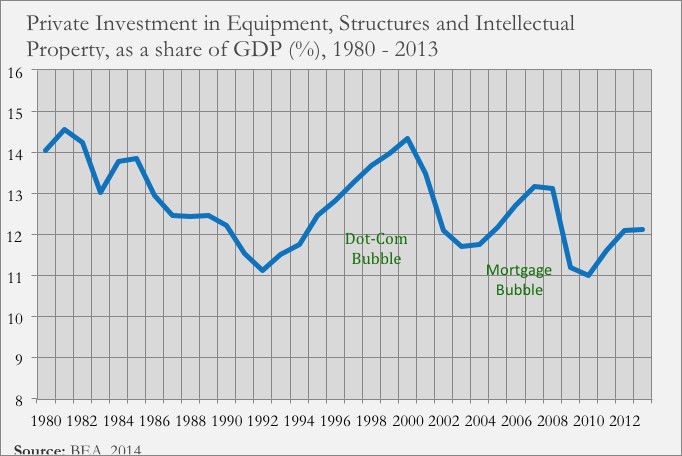

In today’s corporate culture, management eschews future prospects and simply distributes the cash. When asked in surveys, CEOs tell us that if a new investment hurts this quarter’s share price, they will forego it even if it promised a more profitable company in the future. As shown below, productivity-enhancing investment decline has been the norm for decades, except in times of price bubbles when irrational exuberance grips the markets.

Meanwhile, incomes from wages have stalled and businesses’ cost of labor to produce products and services has flat-lined, increasing less than 0.49 percent per year since the financial crisis. Having opted for profits without investment, companies have been able to keep employment to a minimum and wages stagnant as job opportunities shrink. Nowadays, it takes years for employment and salaries to claw their way back from recession, a phenomenon that began to surface in the 1990 recession and has been a millstone around the neck of the American worker in the six years since the Great Recession ended.

Related: 10 CEOs Who Make Way, Way, WAY More Than Their Workers

At the same time, governmental investment in the future has dwindled to a trickle as austerity and legislative gridlock define what government can do. Because of backend-loaded budget cuts, non-defense public investment is projected to diminish to less than 1.25 percent of GDP by 2022, levels not seen since Eisenhower’s administration.

America’s dreadful infrastructure, the income and wealth inequality crisis and the massive shortfall in investment to address climate change are outgrowths of this public/private shortfall. Given the scale of unmet investment requirements, it is difficult to see how a sustainable future will be funded.

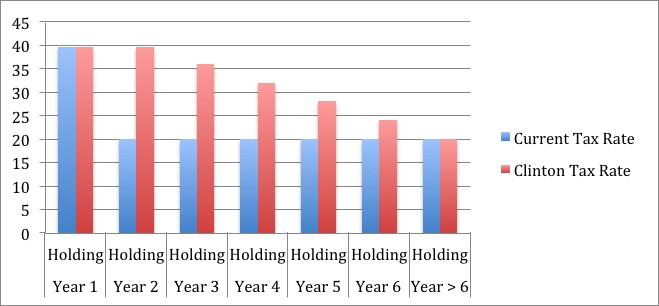

To encourage companies to pursue long-term goals, Clinton’s capital gains policy lengthens the time assets must be held before profits from their sale qualify for the lower capital gains tax rate. Currently, profit on the sale of a capital asset, such as a share of stock or a bond, is taxed at just below 40 percent if the sale is a year or less after acquisition. If the asset is held any longer than one year, a lower capital gains rate of 20 percent applies. Under the Clinton proposal, the higher rate applies for another year after acquisition, then declines to 20 percent over the next four years. The capital gains policy approach is based on the idea that this additional dis-incentive for investors to sell in the second through the fifth holding years will cause companies to pursue longer-term value in order to please their shareholders.

Clinton’s solution will affect corporate short-termism only minimally because, on its own, it fails to address the real issues at hand. The tax angle affects only investors who pay taxes (non-payers do not care what the rate is), leaving out around $17 trillion of pension funds, 401(k)s and IRAs that are not subject to current taxes. Moreover, many taxpayers invest through vehicles like Exchange Traded Funds that buffer corporate managers from the incentive of the higher tax rate, as investors own shares of the fund, not of the corporations. Even rich individuals who may own securities directly have an array of methods of avoiding the tax, developed through years of clever legal advice and generous campaign contributions.

The Clinton capital gains proposal improves on conventional thought and touches on the core problem, which is the matrix of shareholder incentives that drive management behavior. However, it is simply not powerful enough to make a difference.

Related: Here’s an Economic Agenda for Hillary Clinton

The solution to quarterly capitalism must address its real causes, and these are found in the core workings of Wall Street, whose traders dominate the trading markets, promoting single-minded focus by investors, and, therefore, corporate management, on transient short-term stock prices. Because of the massive increase in Wall Street trading, shareholders can readily trade out of a stock at will, diminishing the relevance of future growth. They do not need to wait around for growth when they can easily move on to a new investment that is benefiting from current profits. The ability to buy or sell at reliably discernable prices provides liquidity that has value. But sacrificing the future for current results pushes liquidity to an unhealthy extreme.

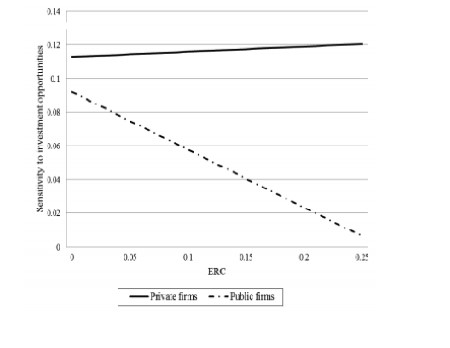

Of course, not all businesses have publicly traded stock. Recent research compares companies having publicly traded shares of stock with those whose stock is not traded. The publicly traded companies are far less likely to invest in long-term opportunities.

The above chart, reproduced from that study, shows that public firms are less likely than privately held firms to invest in opportunities to expand for profit (reflected in the Y axis as “sensitivity to investment opportunities”), and this resistance is even greater among those public corporations whose share prices react most to short–term changes in earnings (the X axis, which represents “earnings response coefficients” or “ERC”). The dashed line, representing publicly traded companies, is always below the solid one, representing privately owned companies, demonstrating that publicly traded firms are less inclined to invest in good projects. And the gap increases for public companies whose share value is more sensitive to short-term earnings changes.

Related: What Elizabeth Warren Has That Hillary Clinton Needs

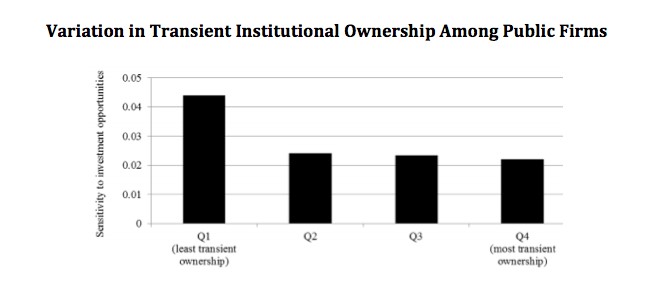

Price sensitivity to earnings is a consequence of heavy trading through which earnings variances can be transformed into price changes immediately. If a company’s shares trade constantly, current earnings are reflected in real time — the trading screen shows prices that are always up to date. It is clear from the following chart (also from that study) that the number of times the shares of stock are turned over in the markets, which is an indication of price sensitivity to current earnings changes, is critical to the company’s propensity to invest.

The solution to quarterly capitalism must address its real causes, and these are found in the core workings of Wall Street, whose traders dominate the trading markets, promoting single-minded focus by investors, and, therefore, corporate management, on transient short-term stock prices. We’ll address a few ways to do that more effectively tomorrow.

Wallace Turbeville is a senior fellow at Demos and a former vice president of Goldman Sachs.