The stock market's historic post-election uptrend has taken quite a breather lately as the Republican health care reform bill stalled out, raising concerns over the rest of the Trump administration’s agenda. Yet the major averages remain with a hair of record territory.

Investors have been spoiled lately by easy gains, lack of volatility and relatively calm newsflow. Before last Tuesday's decline, stocks hadn't suffered a 1 percent pullback since October. Even the Federal Reserve’s interest rate hike, coming just three months after the last rate increase, was greeted by a big market rally. The optimism over global economic growth and reflation, and eager anticipation of a Trump stimulus, overwhelmed any concerns.

Related: 4 Political Minefields Waiting for Trump Following His Health Care Failure

But the mesmerizing recent gains mask a very scary fact: Corporate profits remain at levels first hit three years ago. As equity prices have risen since then, shrugging off everything from renewed weakness in crude oil to the quickening of the Fed's policy normalization, cyclically adjusted equity valuations are now at levels that have only been exceeded heading into the 2000 dot-com and 1929 stock market peaks.

As of March 16, the trailing 12-month "adjusted" earnings per share for the S&P 500 — which is actually an easier measure of profitability since it allows companies to add back or remove things they consider "one-time" events or otherwise unimportant — was $106, according to FactSet. That's just a hair above the level seen on Jan. 31, 2014.

Since then, the S&P 500 has gained roughly 31 percent as investors are now willing to pay much more for the same level of earnings.

It gets worse when one removes the effect of aggressive share buybacks. This method of financial engineering has been popular during this market cycle in part because it masks tepid growth of revenues and earnings by reducing the number of shares outstanding. Without it, based on FactSet data, total S&P 500 net income has fallen to levels first seen at the end of 2011.

Since then, the S&P 500 has gained nearly 90 percent.

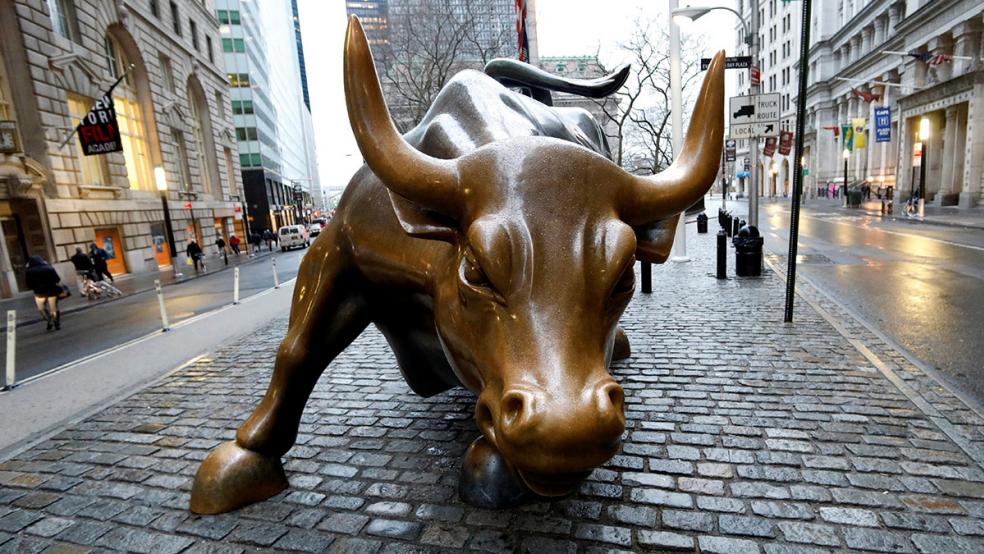

Related: How the Trump Trade Could Turn Into a Trump Tantrum on Wall Street

Focusing on revenue growth alone makes valuations look even worse. For the 30 companies in the Dow Jones Industrial Average — excluding Apple (AAPL) and AT&T (T) since the former replaced the latter in the index two years ago — total revenues now are barely ahead of the total take for 2010, according to data compiled by Wolf Street. That's right. Aggregate sales for America's largest industrial conglomerates are pretty much where they were seven years ago, when the Dow bottomed at 9,614. It's trading just below 21,000 now.

Yet hope springs eternal on Wall Street, as analysts have penciled in S&P 500 earnings growth of 9.0 percent for 1Q17 compared to last year. If this comes to fruition, it will represent the fastest pace of profit growth since the end of 2011, led by a big revenue rebound in the energy sector.

As we’re finding out, that’s a big “if.”

Societe Generale strategist Albert Edwards, well-known for his rare bearish streak among brokerage oracles, warns that it's at this point in the business cycle when "adjusted" earnings measures "become increasingly manipulated" as CEOs and CFOs try to mask margin pressure from factors like a tightening labor market and higher interest rates.

Related: How to See Through Corporate Earnings Smoke and Mirrors

Another factor is the recent upswing in inflation pressure, which the team at Gavekal Research warns played a big role in the "recovery" seen in the second half of 2016 that ended a two-year recession in reported S&P 500 earnings. In "real terms," they believe, there "has been no recovery in profits."