A temporary bump in Medicaid fees paid to primary care doctors, an Affordable Care Act provision intended to get more physicians to accept Medicaid patients, will expire at the end of this month. Congress did not extend the higher rates, so unless states take action themselves or the new Congress revisits the issue, primary care doctors in Medicaid will see their fees fall by an average of nearly 43 percent starting in January, according to a new report from the Urban Institute.

Whether the expiration of the fee increase will make a difference in physician participation in Medicaid is unknown. That is because there hasn’t been enough time to analyze whether the hike actually convinced primary care doctors to take Medicaid patients.

Related: How the Obesity Epidemic Drains Medicare and Medicaid

“It’s expiring before it’s been evaluated,” said Sandra Decker, a researcher at the National Center for Health Statistics, an arm of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Decker, who has published widely on the Medicaid physician workforce, said she will analyze the impact of the fee increase, but doubts her results will be complete before the end of next year.

Still, she noted, past evidence indicates that Medicaid pay increases spur participation by physicians. She predicted that the lower fees will make it harder for Medicaid patients to find doctors willing to see them or that they will have to endure long waits to see doctors who accept Medicaid patients.

A recent report by the Office of the Inspector General in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services underlined the difficulty Medicaid patients already face in getting care. Federal inspectors found that more than half of the doctors identified by states as participating in Medicaid managed care plans could not schedule appointments because they weren’t at the listed address, were not participating in Medicaid or were not taking new patients.

Among providers who did offer appointments, more than a quarter of them had wait times of a month or longer. Daniel Levinson, inspector general for the Department of Health and Human Services, noted that one beneficiary who was eight-weeks pregnant had to wait longer than two months to see a Medicaid obstetrician.

Related: Midterm Election Results Deliver Setbacks to Medicaid Expansion

“Such lengthy wait times,” Levinson said in the report, “could result in a pregnant enrollee receiving no prenatal care in the first trimester of pregnancy.”

Part of the Affordable Care Act

Anticipating a shortage of primary care doctors in Medicaid, the ACA included a provision raising primary care physician rates to the same levels paid to primary care doctors in Medicare for two years. Although states and the federal government jointly pay Medicaid costs, the law required that the federal government pay for the raises. According to the Urban Institute report, as of last June, the fee increase had cost the federal government $5.6 billion.

Even as the provision went into effect, however, many heath economists doubted that it would have long-term impact on participation because the raise was temporary.

Matt Salo, executive director of the National Association of Medicaid Directors, said the fee bump also proved complicated for states to implement. The law was geared toward the traditional Medicaid fee-for-service model, but most of Medicaid now operates in a managed care system, in which doctors are paid a salary. States had to figure out how to translate the raises into managed care models, which, Salo said, took a number of months.

Related: The Family Docs' $20 Million Push to Earn More Money

In addition, Salo said, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services spent a number of months working out other wrinkles caused by the provision, such as coming up with a clear definition of “primary care doctor.”

So, while the raise was welcome, it also caused bureaucratic headaches, Salo said. “Ultimately, it was such a flawed piece of law and execution, you didn’t have a lot of people jumping up and down and saying it needed to be kept.”

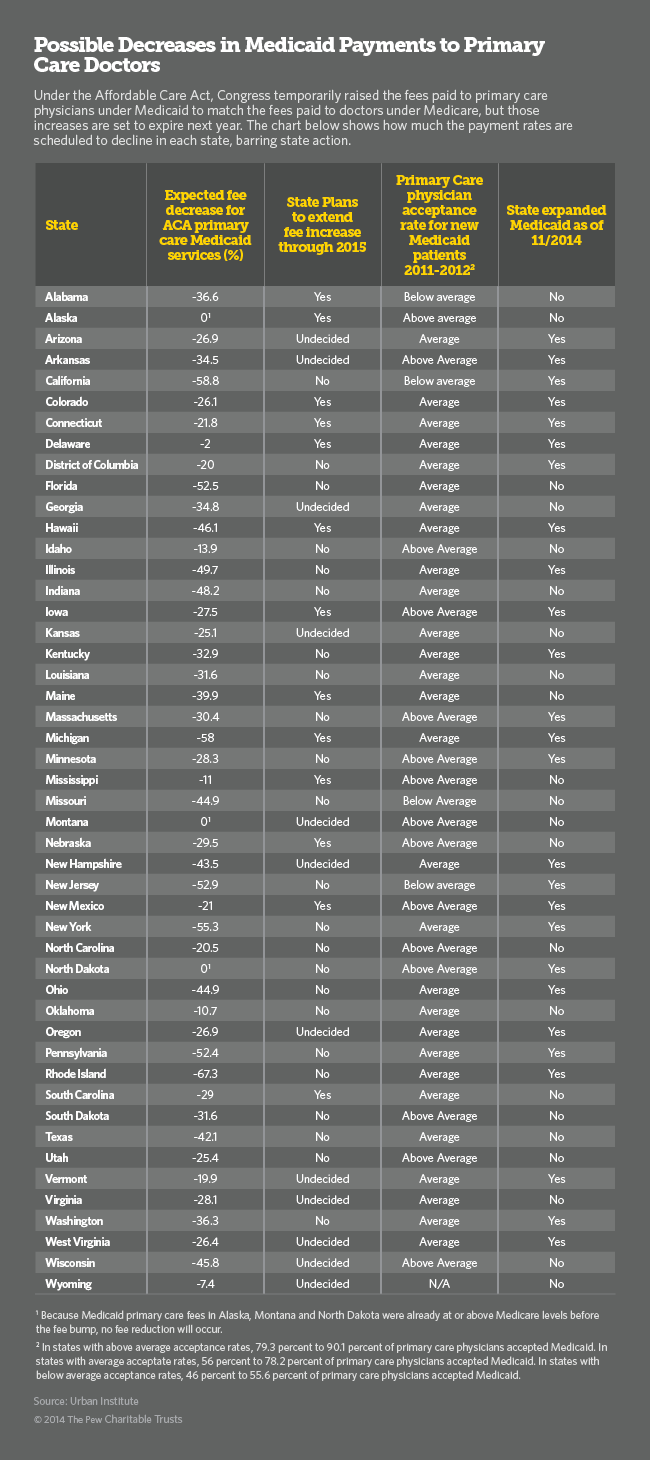

Even so, the Urban Institute report says that 15 states have decided to keep the raises in effect, or at least some portion of the raises. In those cases, the states will share the costs with the federal government based on the formula that applies to that state’s overall Medicaid program. (Under the ACA, the federal government is paying 100 percent of the costs for the states the increased Medicaid eligibility. In expansion states that decide to continue paying higher Medicaid physician rates, the federal government would continue to bear the costs for the expansion populations.)

For some of those states, extending the raises will forestall steep reductions in primary care fees for doctors in Medicaid. For instance, Michigan spared its Medicaid primary care doctors a 58 percent cut in fees. Indiana doctors would have faced a 48 percent cut.

Steep Declines

But Medicaid primary care doctors in other states that have not extended the raise will experience steep declines in their incomes starting in a couple of weeks. Rhode Island Medicaid doctors in primary care will lose 67 percent of their fees. In California, the drop will be 58 percent.

Related: Doc Shortage Could Rise Under Medicaid Expansion

According to the Urban Institute report, the 23 states that do not plan to extend the fee increases cover 71 percent of Medicaid enrollees in the United States.

“No medical practice can sustain such steep drops in payment and keep their doors open to serve patients,” Robert Wergin, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, warned in a statement last week in response to the failure of Congress to extend the raises. “This destabilizing environment cannot continue. The cost to Americans’ well being and to the nation’s coffers is too high.”