Super Bowl Sunday is nothing if not a celebration of excess. Consider:

- 184 million Americans age 18+ plan to watch—that’s three-quarters of the adult population.

- Average ticket prices have surpassed $7,500.

- Advertisers are spending as much as $4.5 million for 30 seconds of airtime.

- More than $100 million will be wagered at Nevada sports books, and perhaps 40 times that will be gambled informally.

- Fans will devour 1.25 billion chicken wings and 27 million slices of pizza—the latter from Pizza Hut and Domino’s alone.

That’s before we even get to the game itself, a contest for athletic immortality waged by impossible-sized men, their girth somehow matched only by their grace as they ricochet around a 360-by-160-foot plot of grass with the chaotic harmony of a New York City rush hour.

Related: Super Bowl XLIX Is Already Setting Records

Like a family driving their SUV to get double bacon cheeseburger combos, everything about the day is wholesale, venti, XXXL. According to the National Retail Federation (NRF), Americans are expected to spend $14.3 billion as they watch the Seahawks battle the Patriots in the big game’s 49th iteration. It’s the nation’s second biggest eating day, a huge weekend for big-screen sales and routinely the record-setter for all-time TV ratings.

Of course, the premise of these gaudy statistics, delivered dutifully by industry trade groups, is that Super Bowl is a powerful economic stimulus; the hope in hyping them is to create an irresistible, almost patriotic, momentum to spend, spend, spend.

But don’t buy it. The numbers are as staged as the halftime show.

That’s because Economics—the science, not the marketplace—gives us three concepts that will deflate those figures faster than a New England football.

If you’re not the details type, here’s the quick summary. You should doubt the much-hyped Super Bowl spending spree because:

1. It’s trivial in the context of the U.S. economy

2. It reduces other types of spending, and

3. It’ll even out soon enough.

Concept No. 1 is marginal value. In many situations, what matters is not the total amount of a certain thing, but how that thing is changing. Suppose it’s late in the fourth quarter and the Patriots are losing by four points with the ball at the Seahawks’ 15-yard-line. Bill Belichick calls a passing play. At that moment, he doesn’t care whether Tom Brady has thrown for 50 yards or 500 for the game; the only thing that matters is those next 15 — Brady’s marginal gain.

Concept No. 1 is marginal value. Suppose it’s late in the fourth quarter and the Patriots are losing by four points with the ball at the Seahawks’ 15-yard-line. Bill Belichick calls a passing play. At that moment, he doesn’t care whether Tom Brady has thrown for 50 yards or 500 for the game; the only thing that matters is those next 15 — Brady’s marginal gain.

Put slightly differently, we’re making the distinction between the base (total yards) and the increment (yards on that play). Sometimes, our interpretation of the outcome depends on an additional step: Evaluating the increment relative to the base. If Brady’s pass results in a touchdown, the Patriots gain six marginal points. Since they were down by four, that’s a big deal—it’s the difference between victory and defeat. If they had been winning by 30, one extra touchdown wouldn’t matter so much.

It’s the same with Super Bowl spending. In the abstract, $14.3 billion sounds like a lot. But U.S. consumers will spend about $12 trillion this year. In that context, $14.3 billion is a rounding error.

Related: The Super Disappointing Economics of the Super Bowl

If we want to be a bit more charitable to the NRF, we can step down to the daily level, where the impact is more noticeable—but still surprisingly small. On an average day, American consumers spend about $32 billion. Let’s say Super Bowl spending is spread out over five days (it takes time stock up on nachos and beer). During that time, fans’ $14.3 billion will be subsumed by the $161 billion in spending that regularly takes place. Even if we (unrealistically) assume Super Bowl spending is pure gravy — not interfering with regularly scheduled spending by, say, keeping a family from going out to dinner that same evening — it’s a boost of only 9 percent. Not nothing, but not exactly huge.

And the fact is that the Super Bowl does displace other activities. Which brings us to our second concept: opportunity costs. Time and money are finite. For every choice you make, there is an alternative. The most valuable of these alternatives is what economists call an opportunity cost.

Think of the Seahawks facing 4th-and-1 at the goal line. If Pete Carroll elects to kick a field goal, Seattle will almost certainly gain three points. But they are giving up the chance of going for a seven-point touchdown (assuming a successful extra point). Even if the probability of success is only 50 percent, that implies the Seahawks are missing out on an expected 3.5 points—the opportunity cost of the field goal. Bad decision. (And, actually, NFL teams are successful more than half the time on 4th-and-1’s, even from the goal line.)

Related: Deflategate Follows Patriots to the Super Bowl

Watching the Super Bowl also has opportunity costs—and they have an economic effect as well. Restaurants are one business that are particularly hard hit. According to the NRF, just 5.5 percent of Americans plan to watch the game at a bar or restaurant. How does this compare to a typical Sunday?

As it turns out, restaurant industry data is fairly hard to come by. But using data from the American Time Use Survey, I estimate that 29 percent of Americans eat out on a typical Sunday (this includes snacks as well as meals, and places like food courts as well as sit-down restaurants). But on Super Bowl Sunday, the number drops to just 15 percent.

A loss of this many patrons is a big deal to restaurateurs. Using data from the Economic Research Service and the Agricultural Research Service at the Department of Agriculture, I estimated that the average cost of a meal out per adult is about $11, which, when multiplied across the 33 million adults who would have eaten out if not for the Super Bowl, comes out to about $367 million.

Restaurants are not the only losers, either. For example, on a typical Sunday during the last three years, Americans spent $35 million on tickets to that week’s top 10 movies. But on Super Bowl Sundays, box office sales plummeted 66 percent, to just $12 million. When you scale up to all movies (the top 10 represent about 88 percent of ticket sales) and include concessions (which constitute about a third of movie revenues), the total hit to theater operators is about $35 million. Given that movies represent about a seventh of household entertainment spending, this implies a $238 million loss across the industry.

It’s a great day to be a pizza delivery guy or a Best Buy investor. But it’s a bad day to be in pretty much any business that doesn’t involve watching football from your couch.

Then again, it’s only one day. And that’s concept three: intertemporal substitution. It sounds fancy, but really all it means is that people can swap things between time periods. Think of it as a law of gravity applied to consumer spending. Given fixed incomes, what goes up must eventually go down. If you buy a new big-screen TV today, as many people do for the big game, chances are that you aren’t going to buy one tomorrow—or for quite a few days after that. (This also goes for chicken wings: If you stuff your face with 25 during the game, it’s a good bet that you’ll probably avoid spicy-sauce-slathered flying appendages for a while.)

Related: The Very Real Cost of Fantasy Football: $6.5 Billion

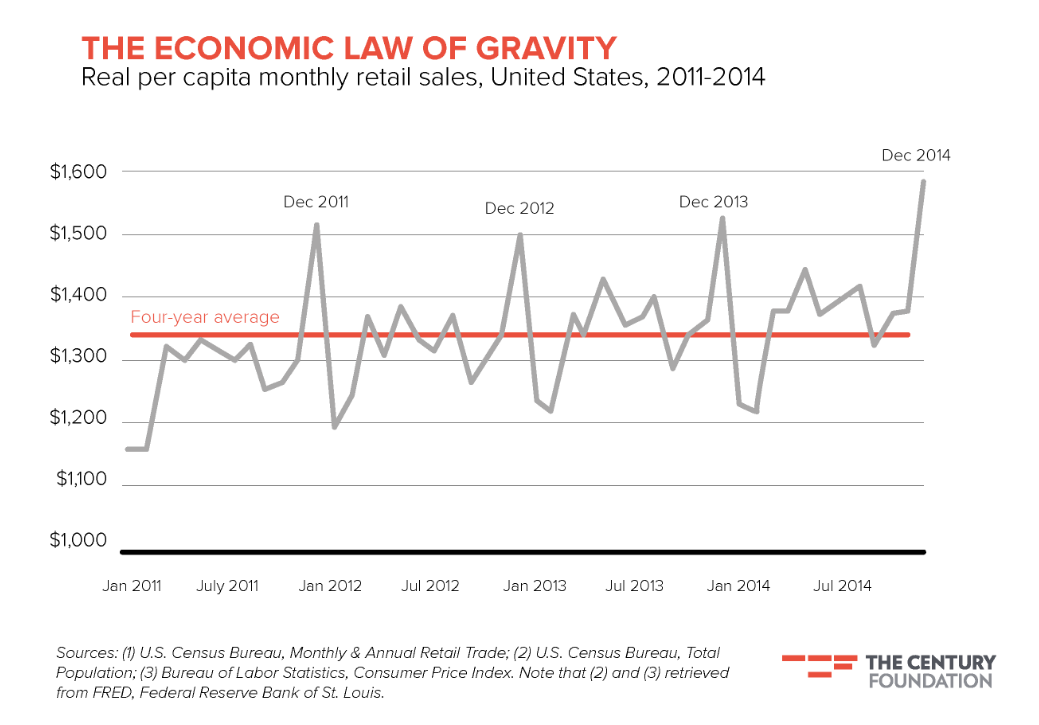

Like other big occasions, the Super Bowl influences the composition and timing of our spending, but it does not much alter its overall volume. To see this in action, take a look at the figure below, which charts monthly retail sales, from 2011 to 2014, adjusting for inflation, population size, and the number of days in the month. Compared to the average month, December averages 13 percent greater sales, a gain of $54 billion. But January is its mirror opposite, with sales 12 percent less than normal. Take the two months together and everything evens out. Gifts given in December are not given in January. The holidays don’t create economic growth; they alter spending patterns. What goes up must come down.

What’s more, for all the attention consumption gets, it actually has quite little to do with economic growth. While demand for products is crucial in recoveries from recessions, spending is often as much a reflection of a healthy economy as it is a cause of it. As economists have long demonstrated, the true determinant of long-run growth in productivity is saving, not spending — that is, investment. Eating pizzas will make us happy today; delaying gratification and saving for better roads, faster Internet networks, and more accessible college educations will ensure we can eat more pizzas for years to come.

Or, to put it more simply, when the stimulus in question involves large numbers of people sitting on the couch eating junk food and watching TV, chances are its economic value is anything but super.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: