Satiric comedy almost never ages well, dependent as it is on timing, flaunting social norms and clever references to culture. Viewers need to be on the same page as the artist and the passage of time makes that difficult. It takes a talented cast to pull off a Shakespeare or Moliere comedy--even wildly successful sitcoms from as little as a decade or two ago can seem stilted or offensive.

It is the rare work of satire that can stay evergreen and topical, and it usually helps if the comedy has bite. Jonathan Swift’s call to eat Irish babies, for instance, still has teeth because we still feel the sting of demanding employers that can seem heartless and indifferent. And despite its 1976 release date, there are few works more appropriate to our fever dream, politically obsessed times than “Network,” which makes it all the bigger shame that it is mentioned so little.

*Spoilers ahead for a four-decade old movie, if you care about such things*

“Network” is set in a period when the media was undergoing a real transition. Early televised news was more staid and direct, a descendant of the newspaper and radio style that had preceded it. By 1976, it was clear that television was a business, and the business was driven by ratings. Straight news may be responsible, but it doesn’t get eyeballs on the screen. Sound familiar?

Related: Here's Why Donald Trump's Lies May Be Good for U.S. Politics

Crucially, “Network” chooses as its main character a former newsman, now television executive, already feeling lost and irrelevant in this new landscape. Matinee idol handsome in his youth, William Holden’s life of hard drinking had left him a very weathered looking 55 — a trait he used here (and famously in “The Wild Bunch”) to betray an immense weariness, and his sad eyes are the focal point for the audience.

But the wild characters around him stick in one’s memory and make the film’s point. Faye Dunaway, who had just finished “Chinatown” and was nearing the end of a long winning streak that had started with Bonnie and Clyde (1967), plays one of the early iterations of a character that would become more common in the ‘80s: the professional ice queen who even talks ratings during sex. It is her ambitious nihilism that drives the plot of the film, and she is clearly meant to represent the evil corporate overlords that control the media.

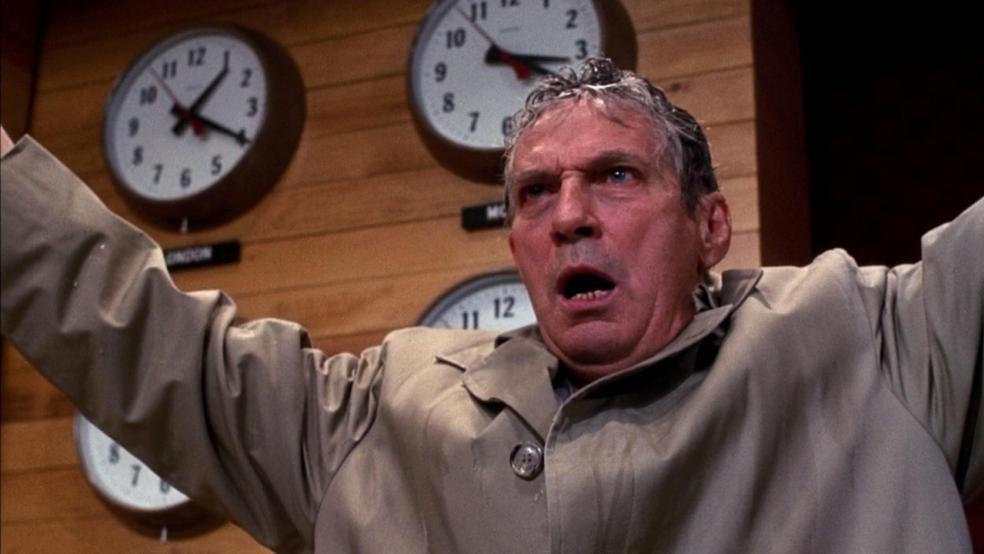

The character who has best stood the test of time, and holds special relevance for us, is Peter Finch’s Howard Beale. Informed that he will be laid off in two weeks, the old news anchor goes on a bender only to show up at work the next day still drunk. He announces during the broadcast that he’ll commit suicide on air.

The suits upstairs talk him down, but he’s back on the air the next day (why they let him back on is beyond me). Rather than issue the agreed upon apology, he launches into a rant against society that many people quote to this day without necessarily knowing the source. Beale’s rant ends in a wild, fire-and-brimstone call for the people of New York City to open their windows and scream out, “I’m mad as hell, and I’m not gonna take it anymore.”

This is where things get really crazy.

As the screams grow louder across the city, Dunaway’s Diana Christensen realizes she has a ratings bonanza on her hands and immediately gives Beale his own talk show that’s equal parts Jerry Springer, Glenn Beck and WWE a decade before any of this existed. The crazier the things that Beale says, the more his ratings go up. Finally he goes too far by attacking the Saudi ownership of the station. The corporate overlords, in a chilling monologue by actor Ned Beatty, tell him to back off, but the defanged Beale starts losing ratings. So the two for one solution? Assassinate him on air and produce the show’s biggest ratings stunt.

The film was itself released in a period of transition. Jaws (1975), Rocky (1976) and Star Wars (1977) would shift Hollywood’s focus from the kind of thoughtful New York-centric films director Sidney Lumet was known for (“Dog Day Afternoon,” “Serpico”) to giant feel-good films that raked in the big bucks. “Network” was still one of the biggest films of the year and did well at awards time (though it lost Best Picture at the Oscars to “Rocky”).

Related: The 17 Best Political Films of Our Times

At the time, the film seemed wildly over the top. Revered film critic Pauline Kael hated the film for its wild-eyed performances and didactic speeches, but seen now in an age of Donald Trump, Real Housewives and the Kardashians, it seems positively prescient and (until the end) restrained.

And while it’s easy to see Trump in Howard Beale’s rants and to see Internet news, so dependent upon outrage to drive revenue (while an older generation of journalists looks on in horror), in Diana Christensen, it is also worth focusing on the people who screamed out the window.

We don’t open the window anymore, we post in comment threads or on Facebook or Twitter.

Whether you’re worried about climate change, ISIS or the second coming of the Big J.C., we all think the world is ending and “those fools” on the other side just won’t listen. Even our most popular fairy tale (well, aside from “Star Wars”) has its heroes beheaded and its princesses violated.

We live in dark days, but films like “Network” remind us that we’ve been here before, and that maybe we can learn from that.