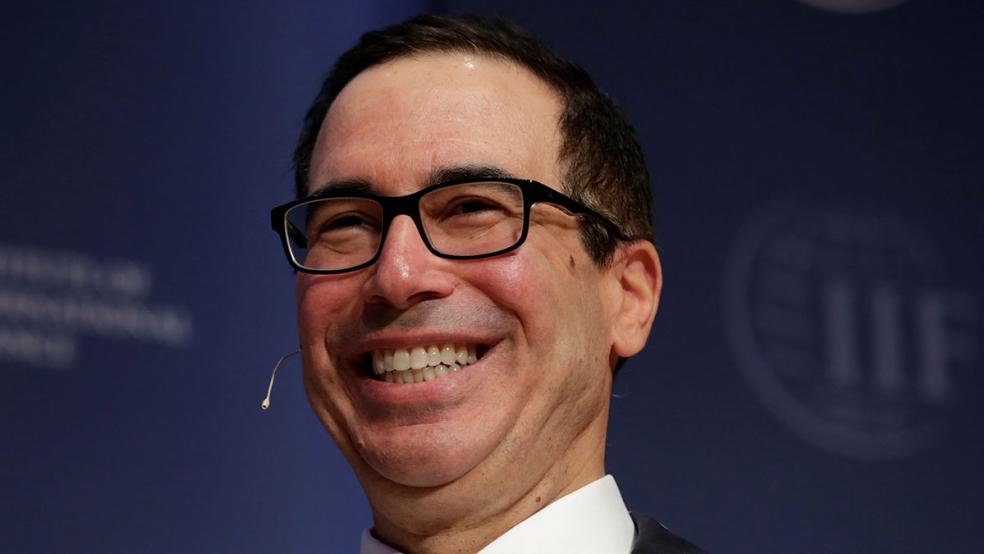

Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin on Thursday said that the Trump administration is prepared to move forward with a plan to overhaul the tax code, regardless of the fate of Republican efforts to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act.

As President Trump approaches the arbitrary but much-discussed “100 Day” mark in his term, Mnuchin said that the legislative slowdown caused by the attempts to pass the American Health Care Plan had given Treasury needed time to develop a tax plan that they are designing “from scratch.”

Related: Why Trump May Eliminate a Tax Deduction Claimed by Millions

“We would not have been ready to go a month ago on tax reform, and now we are,” he said in an appearance before the Institute for International Finance. Describing a tax overhaul as “a big priority for the president,” Mnuchin said, “Whether health care gets done or health care doesn't get done, we're going to get tax reform done.”

However, Mnuchin also made some comments likely to make deficit hawks nervous. Specifically, when he was asked if the tax plan presented by the administration would be “revenue neutral” -- meaning that it would not reduce the overall income to the Treasury, he replied that the plan would “pay for itself.”

What this reveals, as Mnuchin later clarified, is that the White House will be depending heavily on a process called dynamic scoring to demonstrate that the plan it proposes won’t drive the country further into debt. Unlike traditional scoring, dynamic scoring attempts to predict the effect policies will have on economic growth and to factor that into the proposal’s overall impact. Economists are divided on how accurate dynamic scoring models are, but there is wide agreement that they are at best a broad estimate and not a precise measure.

Related: Behind the Campaign to Kill the Trillion-Dollar Border-Adjustment Tax

During his campaign and since, Trump promised to slash business taxes by more than half and to cut taxes on individuals as well. The proposals, usually expressed in fairly general terms, would cost the country trillions of dollars in revenue over a 10-year budget window, and the administration has yet to identify spending cuts or other revenue sources that would make up the difference.

That leaves economic growth to do the heavy lifting, and it’s no small job. Different analyses of a tax plan Trump released during the campaign all showed his proposals costing the Treasury between $2.6 trillion and $9 trillion over the space of a decade. One of the most sympathetic analyses, from the conservative-leaning Tax Foundation, scored Trump’s proposal dynamically and still found it cut revenue by nearly $2.6 trillion over ten years.

That’s a real problem for the administration if, as Mnuchin warned on Thursday, the tax reform package has to be passed as part of a budget reconciliation package in the Senate.

Related: The Tax Credit Both Parties Support – Except It’s Rife With Fraud

The reconciliation process, which Republicans are currently trying to use to repeal the Affordable Care Act, has the benefit of avoiding the filibuster in the Senate. But it also comes with a major restriction in the form of the Byrd Rule, which prevents it from being used to pass legislation that would add to the federal deficit beyond the 10-year budget window.

Effectively, that means that unless the administration can convince the Congressional Budget Office and the Joint Committee on Taxation that its reform proposal is at least budget neutral in the long term, it won’t be able to pass the Senate without legislative tinkering similar to the “sunset” provision that caused tax cuts passed in the early years of the Bush administration to expire early in President Obama’s first term.