“The spending deal reached by congressional leaders Wednesday marks an end to the budget austerity congressional Republicans sought to advance in Washington in 2011,” Nick Timiraos writes in The Wall Street Journal.

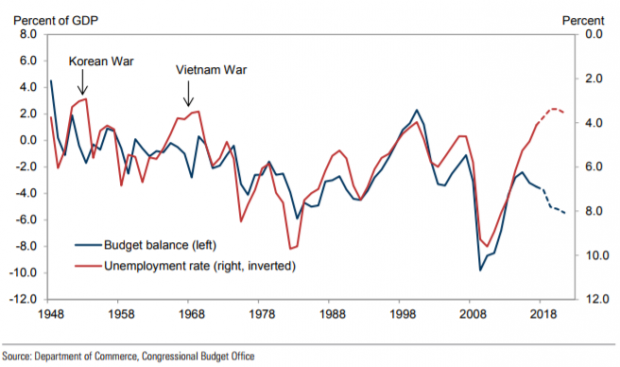

The agreement helps speed a rapid return to $1 trillion budget shortfalls, and it represents a sharp departure from the more typical fiscal cycle in which deficits rise during economic downturns and then get reduced once the economy recovers and expands (see the Goldman Sachs chart below, via economist Jared Bernstein, whose post here is worth a read). “Hard to overstate how backwards we’ve been on fiscal policy, banging on with austerity/debt ceiling fights following a deep recession and spending like sailors as economy heats up. Quite insane,” Politico’s Ben White tweeted Thursday morning.

It’s also a momentous departure from other budget deals of recent years in that it not only sets aside the automatic “sequestration” cuts that were first triggered in 2013, as past deals have done, but also pushes past the spending caps set by the 2011 Budget Control Act. “This is important because once lawmakers raise spending above the cap for just one or two years, it is very hard to return below them,” Timiraos writes.

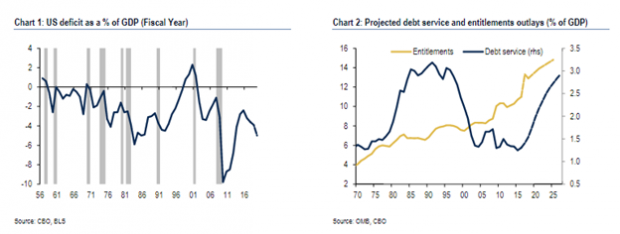

The deficit has been rising and was already projected to continue climbing in the coming years as a result of demographic trends, tax cuts and higher interest rates. Bank of America Merrill Lynch economists noted in a research note this week that the deficit has become the fastest growing part of the economy. After falling sharply from its high in 2009, the deficit has climbed from 2.4 percent of GDP in 2015 to 3.4 percent last year. It’s projected to hit 5 percent of GDP in 2019, according to the economists. “That would be double the historical average and by far the biggest deficit for the economy when at full employment since World War II,” they wrote.

The projected deficits beyond that may escalate quickly if the tax cuts set to expire in 2025 are extended. “Meanwhile, both entitlements and the cost of servicing the debt are rising steadily as a share of GDP,” the Bank of America team wrote.

Fiscal hawks and many economists warn that the large and rising deficit poses a real risk to the economy, potentially "crowding out" private investment, leading to higher inflation and interest rates that stifle the economic gains from tax cuts and other stimulus.

We should note, though, that some other economists say this kind of added boost may be just what we need to bring the last of the discouraged workers off the sidelines and finally create robust wage growth. The benefits, they posit, might outweigh the risks, especially if the money is spent wisely. Bernstein, for example, says the unemployment rate could fall as low as the mid-3 percent range, driving wages higher after decades of stagnation.

“If majorities of policymakers are unwilling to pay for necessary, progressive initiatives, we will have to accept larger deficits,” he writes in The Washington Post. “That means accepting the risk that higher deficits could lead to higher inflation and interest rates, expensive increases in debt service, or restrictive fiscal space, while building support for a more balanced fiscal policy should those problems surface.”