A deteriorating job market is complicating bi-partisan negotiations to raise the federal debt ceiling, as Republicans continue to demand sharp reductions in federal spending despite warnings from the Federal Reserve Board and the Treasury that doing so could under-cut the recovery.

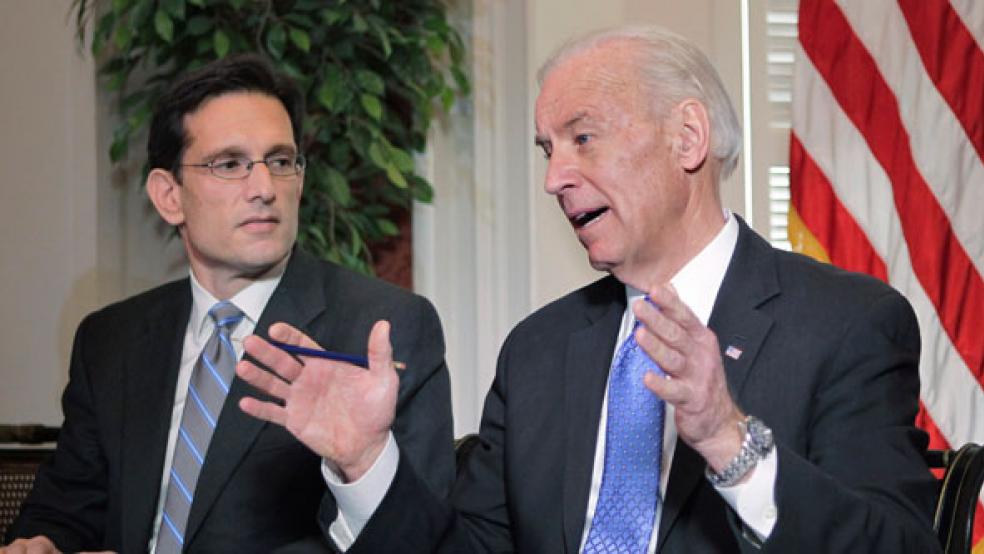

After a two-and-a-half-hour, closed-door session at the Capitol Thursday, lawmakers emerged from talks without a deal to raise the debt ceiling, and confirmed that economic conditions are weighing heavily on the negotiations. The talks are being chaired by Vice President Joe Biden, and include Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner.

“It’s a concern,” said Rep. Chris Van Hollen, D-Md., the ranking member of the House Budget Committee, when asked if last week’s jobs numbers, which showed unemployment ticking up to 9.1 percent, had come up in the meeting. He brushed past reporters without offering a formal statement.

Rep. Eric Cantor, R-Va., the House Republican majority leader, also pointed to a grim jobs report, saying it "has to do with the fact that there isn't a credible plan to manage down the debt and deficit in this country, and that's what we're trying to do," he said. Cantor added the negotiators had agreed to resume the talks next week.

Republicans engaged in the talks want one dollar in deficit reduction for every dollar increase in the debt ceiling, which now stands at $14.3 trillion. The administration is seeking to increase the ceiling by about $2.5 trillion, which would be sufficient to carry the government beyond next year’s election.

Administration officials say the government will have to stop making some payments, which could include interest on the debt – a technical default – if the debt ceiling isn’t raised by August 2nd. Both Geithner and Federal Reserve Board chairman Ben Bernanke have warned failure to raise the debt ceiling in a timely manner would have catastrophic consequences for the economy.

Many House Republicans, including freshman backed by the Tea Party, dismiss those claims. They accuse the administration of “scare-mongering.”

In recent days, many economic prognosticators have begun ratcheting down their economic forecasts for the year. The Labor Department last week reported the economy added just 54,000 new jobs in May, far below previous months. Slower job growth in the private sector was made worse by government job shrinkage, primarily at the state and local level.

Analysts say sharp cuts in federal spending this year, which many Republicans in the House are demanding as part of any debt ceiling deal, would serve as a further drag on the economy. Some economists even argue the economy has become so weak that immediate spending cuts now would actually increase the deficit, since it would reduce tax collections as people lost jobs.

Federal Reserve Board chairman Ben Bernanke in a speech in Atlanta earlier this week expressed similar concerns when he spoke out against immediate large cuts in the federal budget. “A sharp fiscal consolidation focused on the very near term could be self-defeating if it were to undercut the still-fragile recovery,” he said.

This summer’s slowdown is reminiscent of economic conditions last December, when the economic recovery that had shown some momentum throughout 2010 appeared to be stalling. Even though the Republicans seized control of the House in November, in part by running against out-of-control government spending, the lame duck Congress just a month later with Republican support passed new tax breaks for individuals and businesses, and increased aid for the unemployed.

The new spending gave a one-time jolt to the economy that appeared to put the recovery back on track. But in the past two months, massive supply disruptions caused by the earthquake and tsunami in Japan, rising oil and food prices, and a still moribund housing sector have dragged the economy back into the doldrums.

Related Links

Biden’s Gang of 7: Last Best Hope for a Budget Deal (The Fiscal Times)

Debt Talks Break Two Taboos – Taxes and Medicare (The Fiscal Times)

5 Ugly Truths About the Debt-Ceiling Battle (The Fiscal Times)