Kurt Gilbert of Buffalo, New York, hoped to lower his family’s electric bill two years ago when he left his local utility for a competitive supplier, Energy Plus. The company promised an annual savings of seven percent, or about $100 a year, and other incentives. But by last March, Gilbert’s electric rates were nearly triple what he’d been paying. “My takeaway is that the state-energy-industry deregulated energy market is a buyer-beware industry,” says Gilbert, whose outraged complaints yielded a refund of about $1,000. He’s also back with his local utility, National Grid. (Energy Plus declined to be interviewed for this article.)

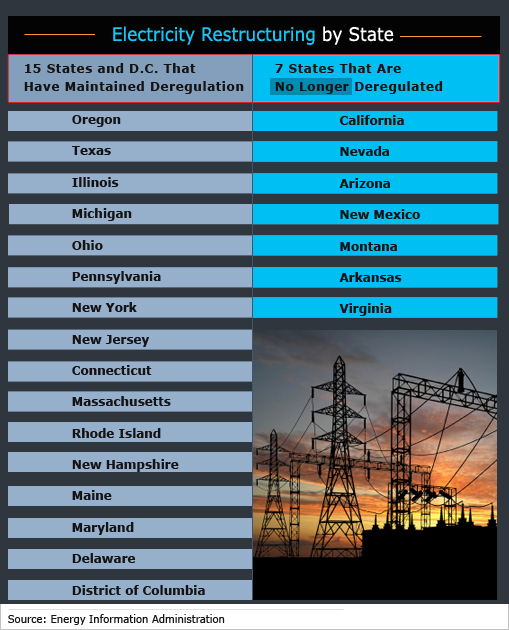

Energy deregulation, or restructuring, was supposed to bring financial relief to electricity and natural gas consumers through choice and competition. But not only have expected savings not materialized – seven of the 22 states that embarked on the program have dropped it after seeing little in the way of rate reduction. Just 15 states and the District of Columbia retain the plan.

“Deregulation has not lived up to its promise,” says Charles A. Acquard, executive director of the National Association of State Utility Consumer Advocates in Silver Springs, Maryland, which represents public advocates and others in 40 states. “We had promises of lower prices and more choice but that hasn’t occurred.”

The states that have halted deregulation include Virginia, where regulators found that “there haven’t been any new competitive offers to provide electricity supply,” according to the Virginia State Corporation Commission. Consumers in states that have kept the program are often flooded with phone, mail and online pitches from energy suppliers promising big savings. Many marketers even dangle enticements like frequent-flier miles and prepaid credit cards – anything to grab business away from local utilities.

Why Results May Vary

But studies of energy deregulation show conflicting results. In May, the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas found that electric rates were lower under restructuring in Texas, Connecticut, Maine and Pennsylvania, where consumer participation was generally strong. But rates were higher in California, Delaware, Illinois, Maryland, Michigan, New Jersey and the District of Columbia, where fewer people signed up. (New York and Massachusetts showed no appreciable price differences.) “If many households are actively switching, suppliers must compete to attract customers,” says Adam Swadley, co-author of the study.

Texas showed the greatest benefit: Residential electric prices decreased at an annual rate of 4 percent; half of all eligible homes were using competitive suppliers as of May 2010. (A state-sponsored website compares competing offers.) But on average, residential electric rates have risen faster in restructured states than in those that never restructured at all, according to Ken Rose, an energy consultant with the Institute of Public Utilities at Michigan State University. From 2002 to 2010, rates climbed 47 percent in the restructured states as a group, compared to 36 percent in states that maintained regulation.

The restructured electric markets pit competitive power suppliers against the regulated local utilities, whose rates per kilowatt hour serve as “prices to beat.” Competitors can dip into the wholesale market when prices are low and pass along the savings to consumers, while local utilities typically buy their electricity on a more rigid schedule. “As a competitive supplier, we’re free to purchase our energy whenever we wish and sell it at retail,” says David Fein, vice president of energy policy at Baltimore-based Constellation Energy Group, a Fortune 500 power company that is being acquired by Chicago’s Exelon Corp. in a $7.9 billion deal.

Competitors like Constellation typically offer consumers one- and two-year contracts at rates below the local utility’s current price. “We sell a fixed-price product,” says Fein. “The customer is going to enjoy that fixed price regardless of what happens in the marketplace.”

Early Bargains – Followed by Rate Changes

While households that lock in deals receive an initial bargain, they can end up paying more than the local utility charges when its own rate changes. “The benefit of [competitive] contracts is a guaranteed fixed cost per kilowatt hour for your electricity,” says Joan Coughlin of the Central Ohio Better Business Bureau. But “if the [local utility’s] rates go down during the life of the contract, costs can be significantly higher than if you had stayed with your old company.”

The same caveat goes for restructured natural gas markets, which 21 states and the District of Columbia have adopted. In Illinois, the Citizens Utility Board, a state-sponsored watchdog group, found that 9 out of 10 plans from competitive gas suppliers were money losers for households since 2003.

Renee Green of Antioch, Illinois, saw her natural gas rates rise after she switched to a competitive supplier named Just Energy two years ago. She says her rate actually tripled.

“I was floored,” Green recalls. The Illinois Commerce Commission last year fined Toronto-based Just Energy a total of $90,000 for deceptive sales and marketing practices and ordered an audit of the company’s sales and marketing practices.

To protect themselves, consumers can pose a series of questions about the potential benefits and risks of switching to competitive power suppliers. Among the points to consider:

• How does the competitor’s rate compare with the local utility’s rate?

• When and how often does the local utility change its rate?

• Is the competitor’s rate variable – or is it guaranteed for the length of the contract?

• Are there fees, charges or deposits not included in the competitor’s rate?

• Is there a penalty for cancelling out of a competitor’s contract? If so, what is the opt-out period for cancelling without a penalty?

• What happens when the contract expires?

Given the mixed results so far, what does the future of energy deregulation look like? Says William Hogan, research director at Harvard Electric Policy Group, “I don’t think there’s huge pressure to change the rules on the retail side.” So consumers in states offering a choice must continue to exercise due diligence.

From a policy standpoint, restructuring has failed to deliver on the hope of “lowering the price in states that already had very high rates relative to other states,” says energy consultant Ken Rose, who adds, “The restructuring issues that everyone was so passionate about 10 years ago are now just part of the overall landscape. Not a good thing.”