Atlanta Mayor Kassim Reed was reelected on Tuesday after touting his efforts to hire more cops and reform his city’s underfunded pension program. In Massachusetts, State representative Marty Walsh won election as Boston’s new mayor, vowing to keep his eye on the city’s pocketbook and “make sure [I] keep our bond rating high.”

Bill de Blasio emerged as the first Democrat to be elected mayor of New York in 20 years by promising a “progressive path” in the city’s priorities for social spending and affordable housing that could strain Gotham City’s finances.

RELATED: UNFUNDED PENSIONS PUT STATES AND CITIES ON HIGH ALERT

As the U.S. economy gradually recovers from the worst recession of modern times, many city officials are projecting the first year-over-year increase in their cities’ general revenue funds since 2006. Nearly three quarters of city financial officers say their municipalities were better able to meet their financial needs in 2013 than in the previous year, according to a recent survey by the National League of Cities.

There’s still a lot of red ink on city balance sheets to test the management skills of the scores of newly elected mayors who face major fiscal and budgetary headaches. While nothing can match the challenges awaiting Detroit’s mayor-elect, Mike Duggan, whose city is under a receivership and is in the midst of an historic $18 billion bankruptcy proceeding, many other mayors will be grappling with similar unfunded pension liabilities and other retirement benefits, runaway deficits and flagging municipal bond ratings.

Jim Brooks, a program director and researcher with the NLC, said in an interview, “[Cities] retrenched dramatically from 2010 forward . . . even to the point of laying off public safety workers, which had been unheard of for decades. In many cases, cities have a long way to come back to deliver the level of services that are essential to the citizens.”

"To me it looks like cities have weathered the worst part of the [economic] storm quite well, and if we stay on the current track, they should be okay,” added Daniel Mullins, director of the Center for Public Finance at American University. “The problem is that there are still significant disparities in levels of prosperity. There are a number of jurisdictions that are doing quite well and there are a number of jurisdictions that are doing relatively poorly.”

Moreover, across-the-board cuts in federal aid to cities under sequestration and a drying up of federal stimulus funds dating back to 2009 have added to cities’ fiscal woes.

This helps to explain why municipal bankruptcy is a growing problems that goes well beyond the current fiscal crisis in Detroit. Seven other cities, including San Bernardino, Mammoth Lakes and Stockton, CA and Harrisburg, the capital of Pennsylvania, have declared bankruptcy since January 2010. An additional 38 municipal jurisdiction have filed for bankruptcy in that same period.

Jim Powell, a senior fellow at the libertarian Cato Institute, wrote recently in Forbes, “There are sure to be some epic showdowns between (1) interest groups determined to collect everything politicians promised them and (2) taxpayers determined not to pay for other people’s problems – especially since many of the problems involve other people’s pension and health care benefits plans that are much richer than their own.”

Among the possible outcomes of that conflict, according to Powell: More public employee strikes disrupting services, including schools. More creative efforts by municipalities to raise revenue, such as by hiking property transfer taxes or imposing commuter taxes on suburbanites. And potentially more securities fraud as municipalities try to hide their dirty laundry while floating bonds.

A lot of that dirty laundry relates to cities’ troubled pension programs.

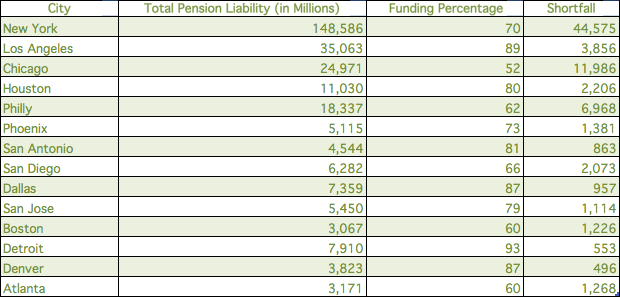

Last March, an issue brief by the Pew Charitable Trust found that 30 cities in the nation’s most populous metropolitan areas faced more than $192 billion in unpaid commitments for pensions and other retiree benefits, mostly health care, as of fiscal 2009. These cities had a long-term shortfall of $88 billion for pensions and $104 billion for retiree health care and other non-pension benefits.

Source: Pew City Pensions Report

“New York, the nation’s largest city, accounted for more than half of the total retirement shortfall,” the study states. “But retirement underfunding looms as a long-term budget stress across a wider array of the cities when looked at on a per-household basis.”

New York, which employs about 75,000 teachers, had unfunded pension liabilities of $14,302 per household in the city, the study noted. Pension shortfalls per household were next highest in Philadelphia at $12,170, Portland, Ore., at $11,389, and Chicago at $11,110.

For retiree health care, the most serious underfunding per household was in New York at $22,857, followed by Boston at $18,962, Detroit at $15,682, San Francisco at $13,487, and Baltimore at $10,208.

Atlanta is also in trouble. It’s $1.2 billion short on pension obligations of $3.2 billion. Their retirement health care fund is in even worse shape. According to Pew, the city has none of the $1.1 billion it needs to pay for retiree healthcare.

Overall, the 30 large cities studied by Pew had 74 percent of the money needed to fully fund their pension plans over the long haul but only 7.4 percent of what was necessary to cover their retiree health care liabilities as of fiscal 2009, the latest year with data available, according to the report.

It’s s not just big cities that are in trouble; smaller cities have similar funding problems. Pew found that few of them had 80 percent or more of its pension liabilities funded. Many of the cities with the lowest funding rates were smaller towns like Charlestown, WV (24 percent funded), Providence, RI (42 percent funded) and Omaha, NB (43 percent funded).

Pew also warned that some cities have been able to hide additional shortfalls with accounting tricks. But changes in reporting regulations will soon reveal the full extent of their troubles.

“Cities for the most part have yet to tackle the looming bill for retiree health care, and the strains will be even greater as baby boomers retire in record numbers,” Pew found. “Cities also are likely to face greater public scrutiny of retirement costs because of financial reporting changes that soon could make their funding levels look far worse than they do today.”

The chart initially suggested the Total Pension Liability was in billions and not millions. This chart has since been amended.

More from The Fiscal Times: