A new report documenting that ten times as many mentally ill people are being incarcerated in jails and prisons as are being treated in psychiatric hospitals and community facilities highlights a massive breakdown in the nation’s mental health system that began a half century ago.

The Obama Administration and Congress have pressed in recent years for greater parity in spending on mental health programs that traditionally have been treated as a stepchild of the $2.6 trillion annual U.S. health care system. The passage of the Affordable Care Act will make coverage of mental health and drug treatment one of the “10 essential health benefits” that all insurers must offer.

An historic shift in mental health care treatment from the states to federal government and local facilities beginning in the 1950s resulted in huge dislocation of the mentally ill, untold suffering by the most vulnerable in society, and a massive increase in the government’s overall cost.

Related: A New Push to Boost Spending on Mental Health

Nationwide, an estimated 356,268 people with mental illnesses including bipolar disorder and schizophrenia are in prisons and jails, compared to just 35,000 who are being treated in state hospitals, according to the study by Treatment Advocacy Center and the National Sheriffs’ Association.

At their peak census in 1955, state mental hospitals held 558,922 patients. Today, they hold a tiny fraction of that number, and states are continuing to close beds.

The tenfold difference today between jailing and hospitalizing mentally ill people is similar to the Dickensian mental health system in the 1830s, before Dorothea Dix and other reformists agitated for legislation to move people with mental illness out of prisons and into hospital care, according to E. Fuller Torey, a psychiatrist and lead author of the new report. .

“There’s been a fairly dramatic continuing increase in the number of severely mentally ill in jails and prisons,” Torrey said in an interview on Tuesday. “It’s gone up progressively since the 1970s. The fact is that in most states the largest de facto mental institution is a jail or prison.”

Many of these mentally ill people end up in jail on relatively minor charges, such as trespassing, stealing food, or urinating in public. Others are arrested for more serious offenses, such as robbery or attacking someone in the street or even murder. And once they are arrested and incarcerated, their lives get swept up in a downward spiral, according to experts.

Related: The Mental Anguish of the Long-term Unemployed

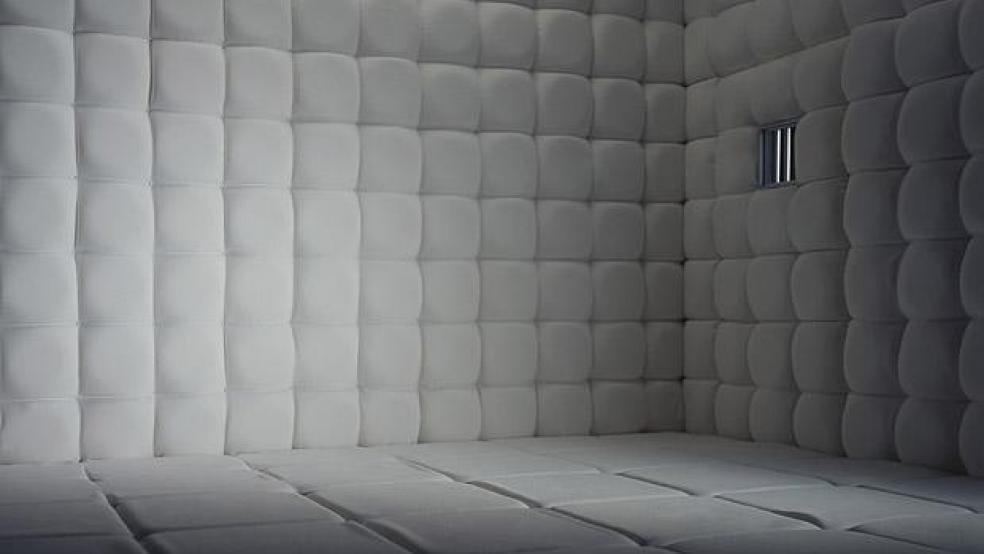

Prisoners with mental illnesses often are put in seclusion for long periods of time, remain incarcerated longer than other prisoners, and are disproportionally abused, beaten and raped by other inmates, the study found. In addition, prisoners with mental illness who are not treated often become sicker.

“The conditions for people who are severely mentally ill living in jails and prisons are in many cases a living hell – and it’s very difficult to treat these people because of the way state laws are written,” Torrey explained.

The study confirms what many mental health care advocates and watchdog groups have been warning for years: that the grand experiment of deinstitutionalization is a massive failure – and a costly one at that.

The federal government spends an estimated $111.7 billion a year on public mental health efforts, including $45.7 billion in Supplemental Security Income (SSI) and Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) payments, $60 billion in Medicare and Medicaid coverage, $5.7 billion for mental health programs under the Departments of Defense and Veterans Affairs, and $386 million for mental health block grants to the states.

Related: 6 Ways Obamacare Is Changing Mental Health Coverage

Spending on incarcerating the mentally ill adds another $10 billion to the annual cost, according to computations by Torrey for his recent book, “American Psychosis: How the Federal Government Destroyed the Mental Illness Treatment System.”

Add to that the costs of law enforcement, courts and public shelters used by mentally ill and the government’s overall annual cost tops $140 billion.

The shift from treatment in state hospitals to community-based facilities initially began in response to complaints about inadequate care, overcrowding and horrible living conditions in the state hospitals. But the states’ primary motive was to offload their financial burden to the federal government.

The shift gained momentum in 1963, after President John F. Kennedy signed the Community Mental Health Center Act calling for widespread deinstitutionalization of patient care. The new law accelerated the emptying of state mental hospitals, with the mentally ill and disabled moved to community health centers, group homes and other residences.

Related: America’s Vets: More Jobs, More Help, More Suicides

But the problems with this new approach became manifest: there weren’t enough community based mental health facilities to handle the deluge; many of the facilities and group homes were poorly managed or ripped off, families often neglected or lost touch with their mentally handicapped members, and mental patients often simply refused to get treatment.

“These people don’t think there’s anything wrong with them and these are disproportionately the ones who end up committing felonies or misdemeanors, ending up in jail or prison or ending up homeless,” Torrey said.

The survey found that in 44 of the 50 states and the District of Columbia, at least one prison or jail is holding more individuals with serious mental illness than is the largest remaining psychiatric hospital operated by the State. The exceptions are Kansas, New Jersey, North Dakota, South Dakota, Washington State, and Wyoming.

Related: 6 Things You Don't Know about Mental Health Care Costs

Indeed, the Polk County Jail in Iowa, the Cook County Jail in Illinois, and the Shelby County Jail in Tennessee each have more seriously mentally ill inmates than all the remaining state psychiatric hospitals in that state combined. In Ohio, 10 state prisons and two county jails each hold as many inmates with serious mental illness as does the largest remaining state hospital.

The report’s authors, among other things, recommend reforming jail and prison treatment laws to allow more easily staff members to administer involuntary medication for inmates with mental illnesses who are gravely disabled, deteriorating or pose a likelihood of serious harm to themselves or others.

The issue of court-ordered outpatient treatment divides the mental health community with organizations like The Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law and Mental Health America opposing it on the grounds that it violates the civil liberties of people with serious mental illnesses, according to Kaiser Health News.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: