If the consensus forecast for the U.S. economy is right, here’s what we have to look forward to in the next few years:

• Tax rates will have to go up. Tax revenue are already scheduled to jump from 14 percent of GDP to more than 19 percent in a few years, as the Bush tax cuts expire—and there will still be a massive deficit encouraging still more tax increases. So when you enter your total tax on line 61 of your 1040 in the next few weeks, take a long look. That’s as good as it’s going to get for a while.

• Continued tight credit, high unemployment—and higher taxes down the road—will keep the economy growing slowly. Recoveries from financial crises tend to be drawn out affairs, and this will be no different

• We’ll become just another superpower. As we struggle to get up off the mat, the world’s economic center of gravity will pass to emerging countries.

Considering that this is a recovery, it’s a pretty dismal scenario. It means it will take a long, long time to get back to the wealth we had before the crash. But enough about money: How is it going to feel? Will our lives be as miserable as the economy’s growth rate?

As it happens, a booming field in economics has opened up to examine such questions, and the research suggests, surprisingly, that we might actually feel just fine. Here’s the evidence:

1) Surprise! The World's Happiest Countries Have High Taxes and Slow Growth

The countries with what economists call high subjective well being (or SWB, a measure of day-to-day happiness) cluster in northern Europe, where high taxes and sluggish GDP growth are standard fare: Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands and that New World outpost, Canada. Those four leaders in national cheerfulness collect total taxes of 49 percent, 49 percent, 38 percent and 36 percent of GDP, respectively. The U.S. has significantly lower taxes (28 percent of GDP) and a history of higher growth, but its reported happiness is actually slightly lower than the Europeans.

The conclusion, known as the Easterlin paradox, after the economist who discovered the phenomenon: After a certain point, high and rising incomes don’t make people feel better off.

Daniel Kahneman, the Nobel laureate who now focuses on the economics of happiness, says that your social life, far more than GDP growth, determines your subjective well being. “You want to make people happier?” he says. “Get them to spend more time with family and friends and less time commuting, especially commuting alone.” To the extent that a sluggish recovery keeps Americans working fewer hours and spending less time in rush hour traffic, it might paradoxically be a net happiness gain.

2) People Adapt to Almost Anything

Carol Graham, a Brookings Institution fellow and author of Happiness Around the World: The Paradox of Happy Peasants and Miserable Millionaires says that one universal truth about happiness and economics is that people adapt. Citizens of Afghanistan are as happy as people in Latin America—that is, above the world average—simply because they’ve learned to live with privation. The adaptive power of the human spirit is so powerful that people who have lost both legs in auto accidents typically return to their former level of reported well being within a few months.

Over time, your economic environment becomes your base assumption and you reset your expectations accordingly. Graham cites a personal experience as an example. “When the tires were recently stolen from my car in Washington, DC, I was unhappy,” she says. “But had it happened when I lived in Lima, Peru, I’d just have wondered why I left the car outside. It wouldn’t have been as big an event, even for the same person.” To put it in the context of our anemic recovery: You may not like higher taxes and slower growth. But as long as you grow to see it as simply the way things are, you’ll adapt.

3) Higher Taxes Might Actually Make Us Happier

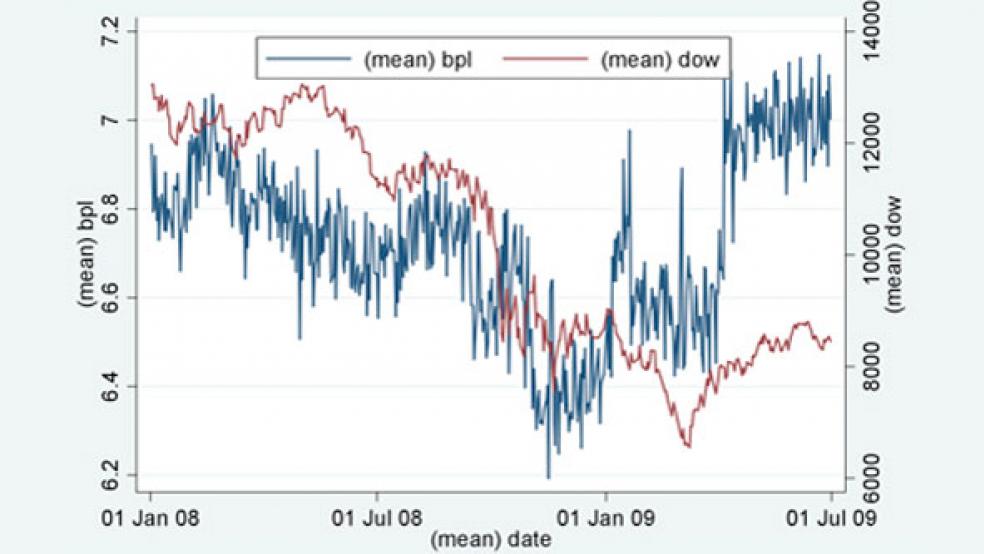

There is one economic factor, however, that people don’t adjust well to: uncertainty. In the Great Recession, Graham notes, reported levels of happiness dropped precipitously through early 2009, tracking the stock market’s plunge. When the Dow started to rebound last March, happiness bounced even faster—even though people described their personal economic situation as actually getting worse. What changed? The period of deep uncertainty about the future had largely passed. “People are much better at adapting to unpleasant certainty than uncertainty,” explains Graham.

Among the most unpleasant uncertainties in the U.S. economy right now are the budget deficit and the entitlement explosion. Neither can be addressed without tax hikes as well as cost cuts. Yes, Washington is still a long way from any serious plan to address these shortfalls, but eventually it will. And the happiness research suggests that people will adapt even if the solution requires some fairly draconian measures. Common sense, meanwhile, suggests that if we take the steps to get our fiscal house in order we’ll be happier in the long run. And we’ll actually have reason to be.

Reporter: Temma Ehrenfeld

Eric Schurenberg is Editor-in-Chief of BNET, the CBS Business Network.