Banks have been on a tear of late, generating by far the biggest gains in earnings from amongst the S&P 500 sectors and generating healthy returns for investors as well. To the extent that they haven’t returned to their pre-crisis dominance of financial markets, that’s just fine. Banks, as a whole, are better-capitalized and more reasonably valued. While some, like Bank of America Merrill Lynch (NYSE: BAC), do command high valuations, Citigroup (NYSE: C) trades at 16 times trailing earnings, JPMorgan Chase (NYSE: JPM) at less than 9 and Wells Fargo (NYSE: WFC) at about 11.4. Why not be optimistic?

The question confronting investors before the Fed’s decision to hold off on the Great Taper was whether or not to take some gains. That question still holds in light of last week’s surprise from Bernanke & Co. and the resulting prospect that interest rates may not rise as quickly.

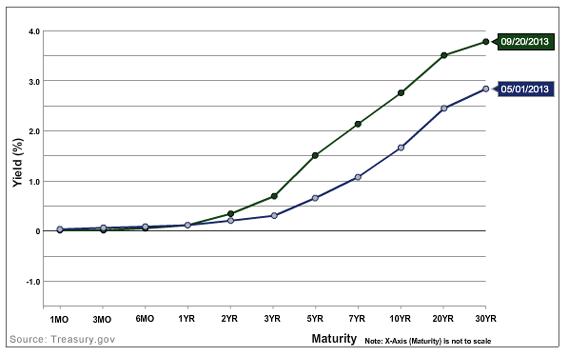

Rising rates are often thought to benefit bank stocks, but the relationship isn’t always so simple. A typical financial institution has different kinds of income-producing assets sitting on its books; as interest rates rise, the value of those income streams will fall. (It’s the classic relationship between yields and interest rates: When rates rise, yields fall and vice versa. That’s because the yield is a measure of what investors are willing to pay to capture whatever the fixed payout is on that security. When rates rise from 3 percent to 4 percent, a bond that pays 3 percent becomes less valuable to an investor, who can now find newly issued instruments with higher coupons; ergo, prices are likely to decline.)

RELATED: 5 YEARS AFTER THE CRISIS: WHAT BANKS HAVEN'T LEARNED

What matters to banks is the shape of the yield curve. Banks borrow in short-term markets and lend out on a longer-term basis, seeking to capture the spread between them as their profit. The steeper the yield curve, the higher the potential return. As Keefe, Bruyette & Woods’ equity strategy team noted in a report published last weekend, the yield curve had been approaching “record levels of steepness.” It’s no coincidence then that banks stocks have been so hot.

Even if we don’t see a meaningful flattening of the interest rate curve that would eat into banks’ net interest margins, other factors could still weigh on earnings. At this point, the most immediate concern for banks isn’t likely to be the yield curve or even the increase in long-term rates, but the impact of the prospect of rising rates on the mortgage market.

Already, banks have been reporting a very significant decline in applications to refinance mortgages, and refinancing has made up a very large chunk of the overall mortgage market in the low-rate environment. The Fed’s monthly buying will continue to support the demand for mortgage-backed securities; mortgage rates are likely to drift lower in the next few weeks.

But even before Bernanke started warning about a taper in late May, some pundits were already wary of the outlook for the mortgage market. After all, unless rates move lower (highly unlikely), where is the extra refi volume going to come from? How many times can a homeowner refinance profitably?

The more a bank is reliant on mortgage lending, the more its earnings are likely to come under pressure in the coming quarters. Some of this already is being priced into the market. Over the last year, Wells Fargo – the single biggest mortgage lender in the U.S. – has seen its stock soar 56 percent, outpacing other giant U.S. banks. In the last month, however, it has gained only 0.4 percent, while Citigroup is ahead 1.62 percent and Bank of America is up 0.73 percent.

One way or another, the odds are high that banking stocks will experience a bumpier ride this fall and winter. The sector will face new or more forceful headwinds from uncertainty regarding any Fed action and the potential impact of higher rates on the mortgage and housing markets.

Regulatory questions still linger as well. Investors, already disgruntled by the inability of banks to generate the same kind of returns on equity that they did in the pre-crisis days, will view any slowdown in the growth in profits as a sign that it’s time to look elsewhere. Restructuring and cost-cutting may not be enough to make up the gap.

This may not be the traditional kind of interest rate cycle we’ve seen in recent decades, but the traditional level of wariness with respect to rate-sensitive stocks may still be the appropriate approach.