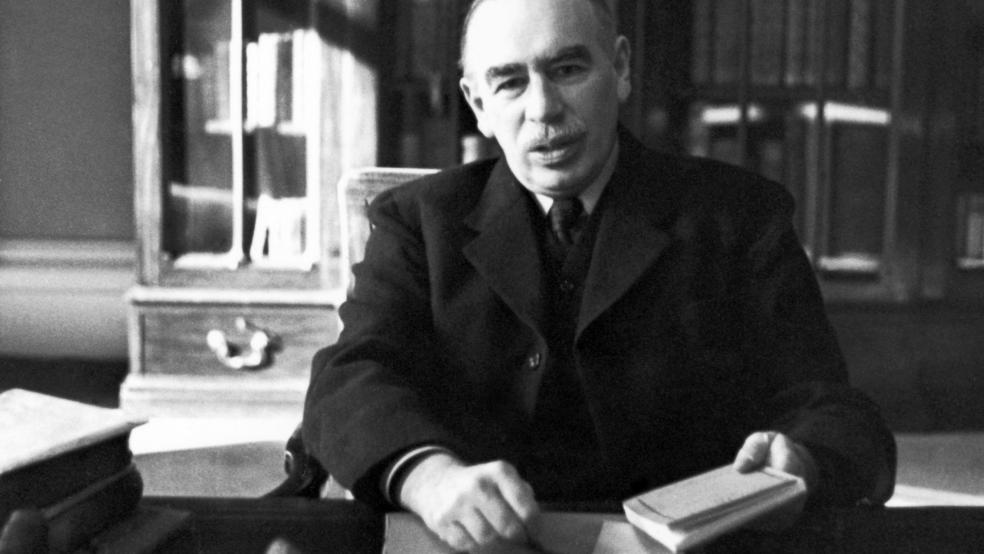

When it comes to the great economist John Maynard Keynes, there are few agnostics. Americans either claim he's a socialist government pest or the savior of our down-trodden economy. Hardly any are on the fence.

Yet Keynes wasn’t just a hugely influential, if divisive, economist — he was an investor, too. When it came to retirement and investing, Keynes was an unlikely champion for doing the right thing to build long-term wealth. Upon exploring Keynes the investor for my book Keynes's Way to Wealth, I discovered a man smitten with the financial markets who was not only a successful personal and institutional investor, but laid the foundation for many established principles in stock investing.

Related: Americans Are Still Idiots When It Comes to Investing

Nearly 70 years after his death, here's why Keynes is still incredibly relevant in helping you invest for retirement:

Keynes Ignored Market Noise. The economist coined the phrase "animal spirits" to describe the irrational herd effect of daily market movements. When he became a long-term investor in stocks in the 1930s at the height of the Depression, he focused on the long-term earnings potential of companies — and not how popular they were. For most investors, ignoring the herd means holding onto a broad-based, total market index fund.

Buy Low and Hold. To any follower of value investors such as Warren Buffett, this is old news. But Keynes started his buy-and-hold bargain strategy after the crash of 1929. He wanted to find companies that would survive, generate earnings and prosper in better times.

Related: Retirement Savings Fears Grip Americans

Dividends Are Divine. Keynes loved to hold onto companies that paid dividends. That meant buying boring companies in shipping, railroads, mining and industrial sectors. Dividends signal that a company is generating cash — and can share their earnings with shareholders. Whether you own single stocks and reinvest dividends in new shares or hold mutual funds or exchange-traded funds that focus on companies growing their dividends, you can gradually build wealth over time.

Today, the best dividend payers are generally not glamorous tech start-ups. They are in staid businesses like consumer staples, financial services and utilities. Cash is king, especially during down times.

Market Timing and Forecasting Is a Mistake. Combining his view that animal spirits contributed to irrational decisions about stock prices with his bargain hunting, Keynes built strong portfolios for two British insurance companies as well as King's College/Cambridge University, his own account and several for friends and families. He essentially stopped employing a "top-down" approach where he tried to predict where the markets were going. He bought on market dips and held on to companies he thought had durable value. While none of this is exciting, it works over time.

Why These Strategies Work

Like all great investors, Keynes stayed in the market when others bailed. He bought when others were selling and ignored forecasts — even during the Great Depression and World War II. As a result, he posted some stellar returns during some of the worst times in history.

If you look at just one of Keynes's portfolios — for King's College/Cambridge — you can see how well he did. From 1924 to 1946, when he died, Keynes achieved an annualized 16 percent return, compared to 10 percent for a British stock index during that period.

Considering that this stretch of time included the crash of 1929, Great Depression and World War II, Keynes's performance is nothing less than extraordinary. But are such returns achievable by non-economists with considerably less education than Keynes?

Adopting a Keynesian investment strategy of buying stocks and holding them through thick and thin still makes sense.

Let's say you held a portfolio of the largest U.S. companies in a plain-vanilla stock-index fund. From 1926 through 2013, you would've returned an annualized 10 percent — and that's if you did nothing, according to Ibbotson Associates. A buy-and-hold strategy with small stocks would've been a better idea, averaging 12 percent a year over that period. Even shorter periods can do fairly well. From 1993 through 2013, stocks only lost money in five years.

Of course, to reap those long-term returns, you have to stay in the market. There's always risk in the short term and no returns are guaranteed. If you just jumped into large-company stocks in 2007, you would've seen only a 3.5 percent return, followed by a 38-percent loss the following year. Yet had you stayed in the market in 2009, nearly every year through last year would've seen a gain, ending with an almost 30-percent return in 2013.

The takeaway from Keynesian investing is elegant yet simple: Doing less will return more.

Forget about investment newsletters, screaming TV pundits and panicky business headlines. If you invested like Keynes did — and can afford the risk of staying in the stock market — you will do well and beat inflation. It's not more complicated than that, although most succumb to the temptation to sell when they should be buying and wait too long to get into the market.

Although the last words Keynes was said to have spoken — "I should've drunk more champagne" — reflected a possible regret over being a workaholic, his investing lessons remain durable reminders on how to build wealth over time.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: