January is not typically a time when people are making summer plans. But thanks to a working paper released this week by the National Bureau of Economic Research, perhaps it should be.

The paper, authored by Alexander Gelber at Berkeley, Judd Kessler at Penn, and Adam Isen at the Treasury Department, found that youth who participate in summer employment programs are better off, at least by some key criteria. But the benefits arrive in ways you might not expect.

Related: How to Teach Kids from Kindergarten to College About Money

Consistent with past studies, the new study finds little evidence that summer job programs increase future employment or earnings among participants. Indeed, for reasons that are not yet clear, their results suggest that participants may actually earn less than nonparticipants in the three years following summer employment. Given that improving young adults’ labor market prospects is often an explicit goal of these programs, this finding is, to put it mildly, disappointing.

But there’s more to the story. Youth who participate in summer work programs are less likely to end up in jail. They’re even less likely to die.

Summer jobs save lives. That’s not a bad tagline.

The Troubles of Youth

To see why youth employment is important, today’s jobs report is a good place to start. With unemployment at 5.6 percent, things are continuing to look good for the workforce as a whole. But those top-level aggregates tell us nothing about how various subgroups are faring.

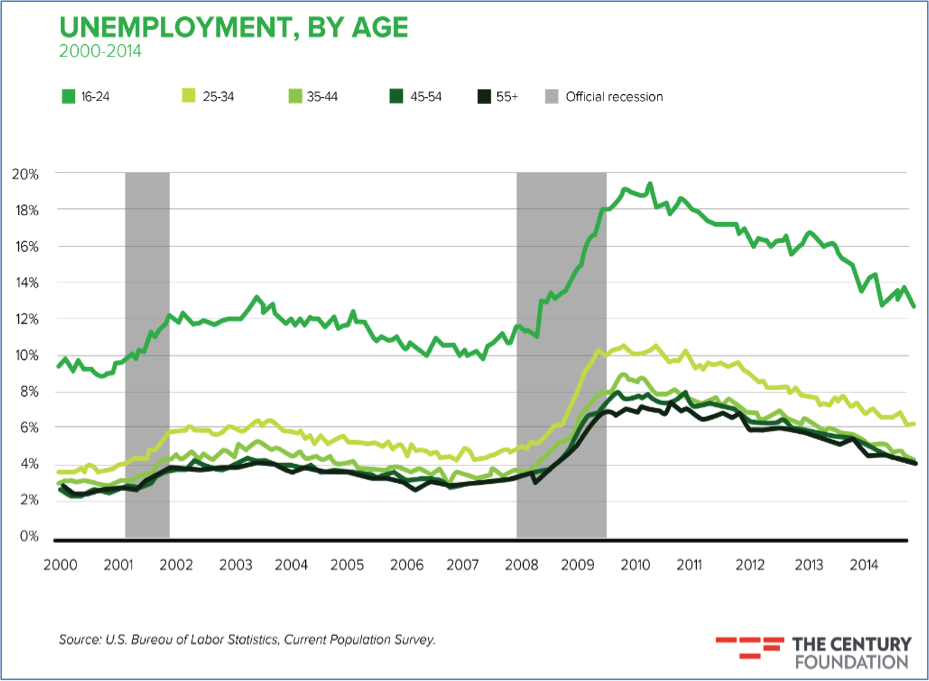

If we parse the data by age group, we see that young people by far are the most likely to be unemployed. At 12.4 percent, the unemployment rate among 16-to-24-year-olds is basically triple the rate faced by 35-to-44-years-olds (4.3 percent) and those 45–54 years of age (4.0 percent).

Let’s acknowledge that youth unemployment isn’t necessarily critical; it’s often a natural part of a learning process. But that’s not to say we shouldn’t be concerned when, as now, youth unemployment is high. That’s because a strong body of research shows that the labor market conditions present when a worker is first employed dictate, to a distressingly high degree, that worker’s career path. If you graduate when unemployment is high, chances are your earnings will be less than they would have been, even decades later.

Related: The Best Paying Jobs for High School Graduates

And the recent difficulties of young people in the labor market are not a new trend; young people have long had the greatest difficulty maintaining stable employment. The figure below, which comes from a recent report I authored for The Century Foundation, tracks the unemployment rates among various age groups from 2000 to 2014, with 16-to-24-year-olds a dramatic outlier. Even today, the youth unemployment rate remains higher than that endured by any other cohort during the depths of the Great Recession.

Why Don’t They Have Jobs?

To dispel a popular misconception: youth unemployment does not necessarily mean they’re in school. By definition, the unemployment rate measures only the fraction of people who are out of work and actively looking for a job.

So what’s up with youth unemployment? Or, more precisely, why is it up?

Well, education does matter—not because school preempts work, but because, quite straightforwardly, many jobs demand levels of education young people have not yet attained. The same goes for experience: older workers have had more time to develop skills, which makes them more productive and more valuable to employers.

There’s another misconception lurking here. As young people have struggled with underemployment in the aftermath of the Great Recession, a conventional explanation is that they’ve been squeezed out by older workers who are delaying retirement longer than previous generations because of declines in their retirement portfolios. In some circles, this is known as the “boxed economy” proposition—the notion that more work by older people means less work for younger ones.

Related: The Surprising Reason College Grads Can’t Get a Job

It sounds plausible, but there’s a serious flaw in the argument: Why assume the economy has a fixed number of jobs? In lots of cases, workers complement each other (think chef and waitress) and, what’s more, one job often leads to others. That is, when one person is working, he or she has more to spend on the stuff others are selling. In fact, research by Jonathan Gruber (yes, the now infamous architect of Obamacare) and others has found that the labor market is precisely the opposite of boxed: older workers delaying retirement is associated with more employed youth.

No, Really, Why Don’t They Have Jobs?

To better understand youth unemployment, we can turn to another NBER paper, this one from October. It turns out the unemployment gap between youth and everyone else can be explained entirely by their propensity to leave jobs, or what is known as their separation rate.

Think of the labor market like an all-you-can-eat buffet. If you’ve been there before, you have a good feel for you favorites, so you’ll probably stick with what you’ve liked in the past. On the other hand, if you’re a first-timer, chances are you’ll take small samples of lots of different dishes as you figure out what you like.

Related: How to Find a Job Without Looking for a Job

This taste-testing is the same with work: People change jobs much more frequently earlier in their careers, when they’re learning what types of positions best match their skills and interests. Because there are usually lulls between leaving one job and starting the next (the technical term is “frictions”), young people spend a greater proportion of their time unemployed.

Even so, a youth unemployment rate of 12.4 percent is still high by historic standards; between 1995 and early 2008, there were only 10 months where youth unemployment was higher than it is now.

It is also not a given that the youth unemployment rate should be three times higher than the rate for prime-age workers — that's a huge gap. It's even higher for minorities and those from disadvantaged backgrounds. Given how important early labor market experiences can be for career trajectories (including future productivity growth), we ought to be concerned when youth struggle to find work. Which brings us back to summer jobs.

The Real Benefits of Youth Employment Programs

Many cities operate summer youth employment programs. Gelber and his colleagues studied New York’s, which, at $66 million and 47,000 participants in 2014, is the nation’s largest. The 14-to-24-year-olds selected for the program work up to 25 hours a week, for six weeks, at the minimum wage, while also receiving workplace education.

Because the program has far more applicants than openings (in 2014, only 36 percent of 130,000 applicants were accepted), slots are allocated via lottery, which creates exactly the sort of randomization researchers live for. Because lottery winners and losers are otherwise identical, it’s much more plausible to attribute differences in outcomes to the program.

Not surprisingly, the program boosts youth earnings (by an average of $876) and employment in the year they participate in the program. But over the next three years, alumni earn about $100/year less than nonparticipants. After four years, employment rates and earnings in the two groups become indistinguishable. And alums are no more likely to enroll in college, either.

To put it bluntly, when all is said and done, the summer youth employment program fails to deliver on what is ostensibly its chief objective: It has, at best, no impact on youth employment outcomes.

The researchers offer several hypotheses to explain this troubling result. For one thing, earnings losses are higher among older participants and those with previous work experience, which suggests that the program may actually interfere with preexisting career development paths. It is also possible that having the program on one’s resume sends a negative signal to employers (“I couldn’t get a job on my own!”) or that it conditions participants to accept low-paying jobs in non-lucrative industries, such as day care.

Related: 10 Astoundingly Weird First Jobs of Famous People

If that were all, the program would seem a popular waste of resources. As it turns out, though, it does offer three pretty important yet somewhat overlooked benefits. First, it is effective as an income transfer. Even factoring in crowding-out of subsequent earnings, participants are still $537 ahead, on average, after four years. Although the program has no income requirement, applicants tend to come from poor families, and these funds can be a boost to household resources.

But the real payoff comes with the second and third benefits—reduced probabilities of incarceration and mortality. While these effects are small in absolute terms (fortunately, such outcomes are rare to begin with), the authors estimate that, as of 2014, the program prevented 112 jailings and 86 deaths among youth who participated in the program from 2005 to 2008.

Incarceration prevention tends to be greatest during the summer in which youth participate in the program, which supports the conventional rationale that such programs “keep youth out of trouble.” The effect also appears to be larger among males, blacks, those without work experience and those 19 and older.

Related: How the U.S. Job Market Has Changed Dramatically in 15 Years

Males, minorities and inexperienced youth also appear to reap the greatest gains in terms of simply staying alive. In particular, the program seems to offer protection against homicide, again underscoring the notion that keeping kids active and engaged can help them avert dangerous behaviors. Valuing outcomes such as these in economic terms is fraught with difficulties, but even under conservative assumptions, it is almost certain such benefits are worth the program costs.

Taken as a whole, these findings suggest publicly funded summer employment programs are marginally effective on the whole, but can be immensely beneficial for specific youth. As with the labor market generally, it’s a question of matching: linking services with the appropriate candidates. Program administrators and policy researches should make it a priority to identify which youth benefit most and why.

Given the scarcity of jobs for youth, and the political appeal programs to help them find employment, limiting eligibility can be unpopular. But it may be best. As localities around the country make plans for next summer (in New York City, enrollment begins in March), they would do well to remember not everyone is right for the job.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: