For weeks now, the New York City subways (and presumably those in other American cities) have been plastered with posters for a coming History Channel event. The posters show modern style portraits of actors portraying a collection of Founding Fathers. It seemed as if History was rolling out an update on 2006’s beloved documentary The Revolution with Hank from Breaking Bad and Elliot from E.T. What actually premiered last night was a different animal, both for better and worse.

The previous documentary is the pinnacle of the style that history/History buffs cry the channel no longer makes, a mixture of largely dialog-less reenactments, talking heads and the stentorian voice of the late, great Edward Herrmann. It’s still an excellent watch, for a very narrow audience. The new miniseries may play faster and looser with the facts and may apply a filter for modern sensibilities, but it ultimately should also reach a wider audience — one in dire need of education about the facts of the founding of our country.

Related: 10 Seismic Shifts That Changed Entertainment in 2014

Sons of Liberty’s title is more literal than you might expect. Rather than being a euphemism for the Revolution as a whole, the show primarily focuses on the exploits of the gang of Boston troublemakers who would eventually form the colonial army in Massachusetts. (Despite the historical accuracy, the callout to Sons of Anarchy is entirely intended).

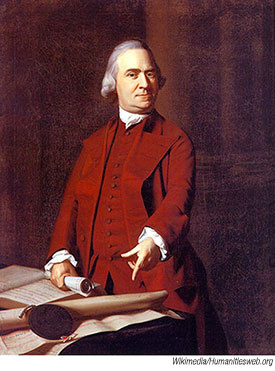

Despite Dean Norris’s top billing as Ben Franklin, the show really belongs to Ben Barnes’s Sam Adams (and the wall-to-wall ads for his namesake brewery during the commercial breaks become a kind of meta-joke). Due to his relative lack of involvement in the post-Revolutionary founding of the country, Adams is often somewhat overlooked as the matchstick that lit the Boston powder keg. This works to the show’s advantage in that the producers do not need to extend the same reverence to him that they would extend to future presidents George Washington and John Adams.

As is the modern tendency for heroes, not much is asked of Barnes other than he brood while having high cheekbones, both of which he does admirably. His character is presented as a sort of halfway point between Robin Hood and Han Solo, without really ever shying away from the fact that he is a smuggler and gang leader.

Related: Hollywood’s Desperate Measures to Save the 2015 Season

Norris only has a few scenes as Franklin, but despite being two decades too young for the part he seems up for the task. Most historians agree that the Revolution turned from unwashed tax rebellion to battle for liberty when Franklin was called before Parliament and treated as a second-class citizen rather than the brightest mind of his generation. The show teases this conflict and hopefully will give Norris the big scene in later episodes.

But the standout of the show (the first part, at least) is Rafe Spall’s John Hancock. Though it is somewhat annoying that they couldn’t find Americans to play Adams and Hancock, Spall’s performance is riveting as a character that’s usually thought of as little more than a giant signature. Spall’s Hancock is an 18th century Gatsby, unable to process that no matter how successful and prosperous he becomes, the Brits will never see him as any more than a backwater colonist rather than one of their own. As Hancock is forced to ally with the unsavory Adams, the man’s façade crumbles further and further. It’s fascinating to watch.

Related: Oscars 2015: All 8 Best Picture Nominees Have One Surprising Thing in Common

In fact, one of the most revolutionary (sorry) aspects of the show is the way war is largely presented as the result of an escalating feud between Hancock and the British governor of Massachusetts. There is an almost Game of Thrones quality to the way that petty grievances and minor slights pile on top of each other toward an inevitable and horrifically violent conclusion. The increasingly draconian measures of the redcoats are (accurately) presented as the attempts of British governors to prevent embarrassment by a group of anarchists.

The American Revolution has been exceptionally difficult to get right on film, at least in part because of the requirement to have lengthy grandstanding speeches about Liberty that in no way resemble human behavior. Stripping out these grandiose moments and focusing on the mercantile origins of the war and the day-to-day cost of the British response in Boston gives the show a human face far more real than a million monologues from animatronic founding fathers that start, “We hold these truths to be self-evident…”

The History Chanel has made The Revolution grungy…and that’s a good thing.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times:

- Playgrounds of the Very Rich and Famous—a 2015 Guide

- 15 Movies to Watch in 2015

- Quantifying the Power of Kim Kardashian’s Butt