Considering how many people in Washington are directly employed in the business of predicting the future, you might think we’d be better at it. But deficit forecasters are always revising their numbers, projects are always going over budget, and the long-term solvency of major U.S. government programs, like Social Security and Medicare, are adjusted – sometimes significantly from year to year.

The truth is, prediction is a very difficult undertaking in complex environments, and the further out a prediction goes, the more likely it is to be not just wrong, but wildly wrong.

Related: How the Obesity Epidemic Drains Medicare and Medicaid

Economists and statisticians know this, of course. But policymakers and the public want hard numbers they can cite on television and argue about in the Capitol. That’s why the Congressional Budget Office is required to deliver precise “scores” of legislative proposals that say how much they will cost over ten years. The professionals at CBO don’t deliver those numbers believing they are dead-on accurate. Their reports explain all the necessary assumptions they had to make about the future, and sometimes provide an indication of how broad the range of likely outcomes really is.

WHY THIS MATTERS

Economic forecasters know that the further into the future they look, the less reliable they are – but that uncertainty is often not factored into policy decisions meant to endure for decades or more. Economists argue that accepting greater levels of uncertainty, and crafting laws responsive to changing circumstances, would lead to better outcomes.

At an event hosted by the Brookings Institution’s Hutchins Center for Fiscal and Monetary Policy Monday morning, a group of distinguished economists and academics addressed the implications of uncertainty for federal budgetary policy, asking the question, “Do we know enough to worry?”

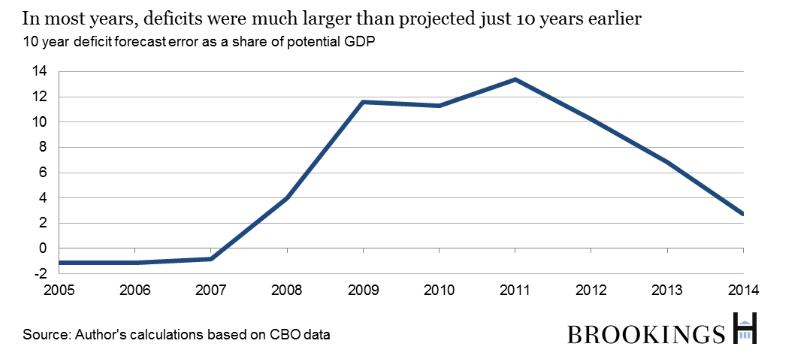

Alan Auerbach, a professor of economics and law at the University of California, Berkeley, presented data calling just how much we know into question. Forecasters, for example, have been particularly bad at predicting the federal deficit.

According to Auerbach, it’s a mistake to match policy to a specific number when we know the number may be off by a significant margin. If we’re concerned about the impact of a large federal deficit and a growing debt, he said, policy ought to recognize that and be adjusted accordingly. Specifically, he said, more weight should be placed on preparing for a reality that is worse than predicted.

Related: CRomnibus Swaps Provision – Some Real Problems, Some Imaginary Ones

“In general, the appropriate response to uncertainty is instead to take more action now, as a precautionary measure against the possibility of worse-than-expected outcomes,” Auerbach’s paper finds. “Hoping for a better future does not constitute an appropriate policy response to uncertainty, and waiting until the size of the problem is known is waiting too long.”

Economist Henry J. Aaron, a senior fellow at Brookings, urged policymakers to “pare back” some of the time frames that government agencies use for projections.

“All projections are based on assumptions around some set of variables and are vulnerable to error, or the variability in predictable factors, as well as uncertainty stemming from unforeseeable circumstances,” he wrote. “Because error and uncertainty grow as the projection horizon is lengthened, in some cases, lengthening the window is not useful and can degrade decision making.”

For instance, advances in medical technology and other factors playing into public health make it very difficult to forecast the health of the Medicare program over the long run, he pointed out. Yet the standard benchmark for solvency is 75 years.

Related: CRomnibus Disaster Signals a Sad New Normal in DC

Uncertainty also has implications for how lawmakers ought to forge legislation, wrote David Kamin, an assistant professor of law at New York University. Congress tends to move slowly, meaning that as circumstances change, laws that were written to deal with them remain on the books even after their effectiveness, a situation he refers to as “policy drift.”

Kamin recommends Congress work to craft laws that are more responsive to changing circumstances, by using tools such as triggers for specific actions, sunset provisions that force lawmakers to revisit legislation, and several other possible methods of compelling change to suit shifting conditions.

The overall theme of the event suggested there should be more tolerance of uncertainty among policymakers in Washington, because it should contribute to better policy outcomes.

However, in remarks to the group, CBO Director Doug Elmendorf, in effect, told them to be careful what they wish for.

Related: IRS Gave $14.5 Billion in Low-Income Tax Credits to the Wrong People

“Providing ranges sometimes muddies, rather than enhances, general understanding of our analysis because people tend to cite the part of a range they prefer,” he said.

And Congress, he pointed out, is a wild card. “It is often unclear how legislators might respond to the quantification of uncertainty, he said. “Further research in this area will be helpful.”

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: