In the Game of Life, the popular, not-so-subtly normative mid-20th century board game, players quickly proceeded to college or on a vocational track, and soon after got jobs, married, bought a house and added the little pink or blue stick figures that represented babies.

With graduation day upon us, 1.8 million bachelor’s degrees will be awarded this year, and many of these young adults will embark successfully on life’s journey. However, for many newly minted college grads and many more non-graduates, especially men, this glide path to adulthood has become the exception to the rule.

Related: Mark Cuban to Millennials—Live Cheap: Clothes, Cars, Don’t Matter

We’ve all heard of or had “boomerang” kids moving home with parents, but it is rarely discussed that young men are considerably more likely than young women to fall off the adult track. Sexism and gender-pay gaps are still real, but the circumstances of a large and growing number of millennial generation men are troubling.

“Millennial men are faring especially poorly,” said David Madland, economic policy director at the Center for American Progress and author of the new book, Hollowed Out: Why the Economy Doesn’t Work Without a Strong Middle Class. “Male unemployment is higher than female unemployment, male labor force participation is lower than in prior generations, their hourly wage is less than it was in the early 1970s, and male educational attainment is increasingly slipping behind women, which doesn’t bode well for the future.”

According to the Pew Research Center and the Population Reference Bureau, 2 in 5 18- to 31-year-old men and 1 in 5 25- to 34-year-old men live in their parents’ basements or their childhood bedrooms, compared with 1 in 3 and 1 in 10 women in each of these age groups. And these numbers have been trending upward, even during the post-2008 “recovery.” One-third of the 30 million men in this age group are not employed, and many who are work only part-time or in low-wage jobs. Two-thirds have never married. By comparison, only 1 in 5 Generation Xers weren’t working and two-fifths of Baby Boomers weren’t married at comparable ages.

For most of these males, the biblical precept no longer holds: “When I was a child, I used to speak like a child, think like a child, reason like a child; when I became a man, I put childish things behind me.”

Related: How Millennials Could Damage the U.S. Economy

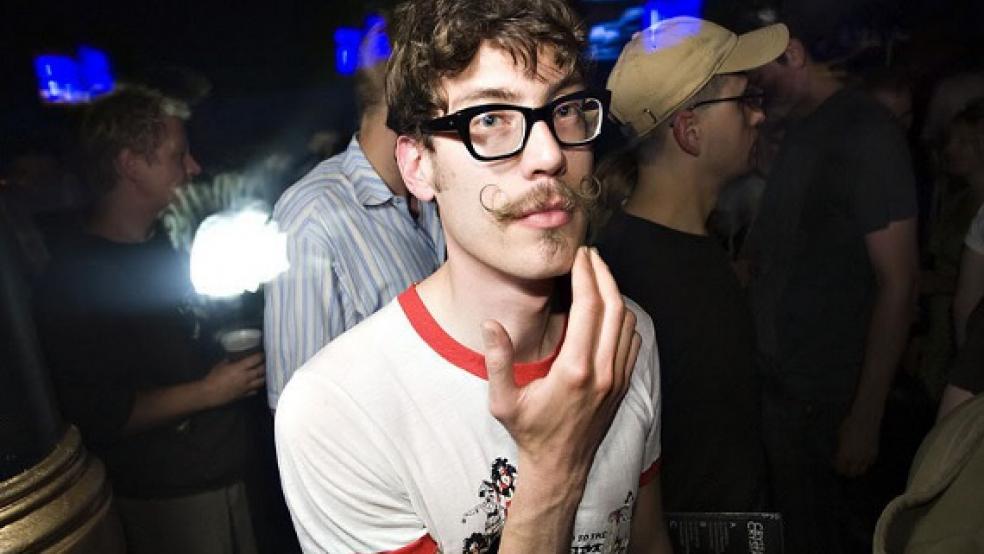

Are these men a 21st century version of Peter Pan’s “lost boys”? Turn back the clock 50 years and American males typically were real “men” by 22 or so — self-supporting, married and ready to start a family. During World War II, millions of 18-year-old men idealistically and courageously volunteered to fight to defeat fascism. Go further back in history, and teenage boys worked in the family business or on the family farm. Such creatures today are extremely rare.

Instead, millions sit home in pajamas, their moms serving breakfast, while spending the day playing computer games, cooking up half-baked business plans, or vegging out with a six-pack in front of the TV. Of course, this loser-like stereotype is not true for all: Many young men work hard in good jobs and are building their lives. Many others try hard to escape the parental basement.

Chalk some of this problem up to a bad economy and burgeoning college debt. Companies are hiring, but many of the jobs are dead-end and low wage, and consumers have become cautious about spending. Yet, does some of this “failure to launch” stem from helicopter parents who have babied their kids into adulthood? Is 25 the new 15?

Related: Why College Professors Are Afraid to Teach Millennials

This disappearance from adulthood of at least 12 million millennial men not only puts a burden on their families, but also spells trouble for their own life trajectories, the U.S. economy, families, and even government finances.

The Census Bureau reports that median incomes for men under 34 have fallen since 1974 (while women’s have increased), and median net worth for those under 35 has fallen by more than one-third in the last decade to a paltry $10,400, according to the Federal Reserve. Many who don’t live at home rely on parents and government benefits to survive.

Although many college grads are in jobs for which they are overqualified, at least college-educated young men have slightly higher median earnings than degree-holders 30 years ago. By contrast, earnings for young men without a four-year degree have plummeted since 1980. Completing this bleak picture, 1 in 5 millennials (both men and women) live in poverty, compared with 1 in 7 in 1980, and, by some measures, income inequality is greater among millennials than among older Americans.

Related: Why American Men Are Falling Fast Behind

The costs are huge. Parents with adult children living at home spend at least eight hours a week caring for them, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics’ time-use data. These men’s lost earnings portend lower lifetime income and savings. The lost manpower reduces America’s potential output. The inability to be providers makes family formation less likely. Adulthood is shortened, as prolonged adolescence marches straight into middle age. The loss of income and property taxes deprives government of much-needed revenue. And the psychic toll for many is incalculable.

What will become of these “boy-men,” as author Gary Cross has called them, and what can turn things around for them?

Certainly, a better job market with decent wages would help. So would expanding vocational and adult training. Over the long term, parents need to hover less and do more to foster independence and responsibility. One way to help these young men — and many women — mature, earn a living, and help their country would be to expand AmeriCorps into a universal, required national-service program for all Americans under 25. In it, young adults could gain experience, responsibility, a modest paycheck and connections, as well as meet key national needs like infrastructure repair, early childhood education and tutoring, reducing environmental hazards, and even providing support for research labs and new businesses.

This piece was published originally in the San Francisco Chronicle on June 5, 2015

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: