The Social Security Administration officially announced on Thursday what economists had expected: There will be no hike in Social Security benefits in 2016. It’s the third time in 40 years that the payout has stayed flat — but those three instances have all been since 2010. The news also means that some people who receive Social Security are going to see their Medicare premiums shoot up.

The size of Social Security checks is adjusted each year to keep pace with inflation, otherwise known as a cost of living adjustment or COLA. Inflation has been flat over the period Social Security measures, so payments will stay the same next year.

Related: Social Security Ruling Drives Up Medicare Costs for Millions

Here’s everything you need to know about how your Social Security checks are adjusted from year to year.

What is the COLA?

It’s not a soft drink. The COLA is an adjustment made to benefits paid under Social Security and Supplemental Security Income, the disability program for low-income people, in order to factor in the effects of inflation. Congress enacted the COLA provision as part of the Social Security Amendments of 1972. Before that, any increases in Social Security had to be approved by Congress.

The adjustment now happens annually and is based on the percentage increase in the Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers (CPI-W). If the CPI-W doesn’t increase during the third quarter of the year compared with the same period the previous year, no adjustment is made to benefits.

How is the CPI-W determined?

The CPI-W is one version of the consumer price index, a measure of inflation tracked by the Bureau of Labor Statistics in the Labor Department. It is based on the prices of “food, clothing, shelter, fuels, transportation fares, charges for doctors’ and dentists’ services, drugs and other goods and services that people buy for day-to-day living.” The prices are gathered across 87 urban areas from 6,000 housing units and roughly 24,000 retailers, from supermarkets and gas stations to department stores and other places where Americans buy goods and services. Those prices are then weighted to reflect the importance of the items in the spending of the population group being considered.

Has the COLA remained flat before? How big is it usually?

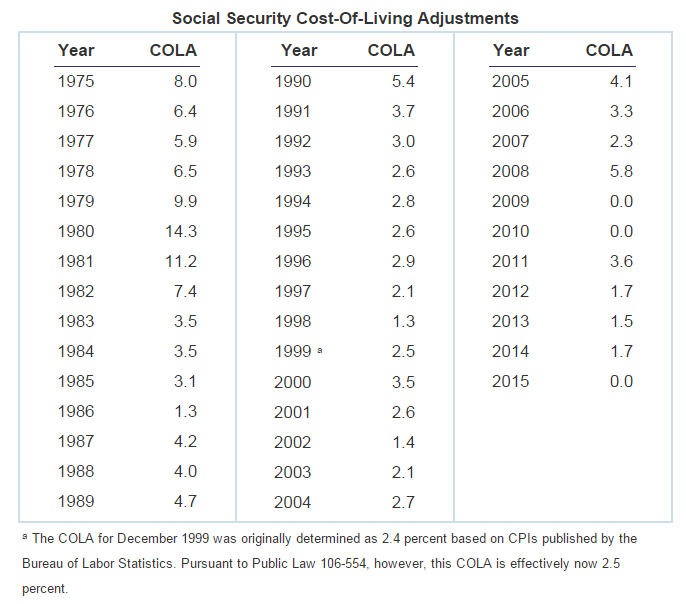

Twice, in 2010 and 2011. From 2010 through 2015, the annual cost-of-living adjustment has averaged 1.4 percent a year, less than half of the 3 percent average during the prior decade, according to the Senior Citizens league. Including 2016, the annual COLA has averaged 2.26 percent a year over the last 20 years.

So the government is saying there’s no inflation this year? How can that be?

The main factor pushing overall inflation down is gasoline prices, which have plummeted 30 percent since last year. Airfares and clothing prices have also fallen by 5.9 percent and 1.3 percent, respectively. Meanwhile, other prices have risen — but not by enough to offset the massive tumble of prices at the pump. Medical care is up by 2.4 percent, housing costs by 3.2 percent and food prices by 1.6 percent.

These price disparities have led some people to say that the government’s measure of inflation doesn’t accurately reflect the prices of the goods and services that the elderly use and that different variations should be used to determine the Social Security COLA.

What are those other ways to measure inflation?

Advocates for the elderly or for expanding Social Security say the government should use a version called the Experimental Price Index for the Elderly, or CPI-E. This calculates the consumer price index for Americans 62 years of age and older, taking into account the difference in spending habits between workers and retirees. Retirees drive less, meaning the low gas prices don’t affect them as much, and they spend more money on health care and long-term care, areas where prices have risen faster than inflation overall.

Others, including those concerned with the long-term cost of Social Security, also think the CPI-W should be replaced — but they argue the current index is too generous and doesn’t reflect how people respond to changing prices in the real world, like switching to buy more chicken if beef prices jump. They favor the COLA being linked to a measure of inflation known as the chained CPI. This measurement would cause the rate at which benefits rise to be slower than if using the CPI-W, because it reflects the substitutions that consumers make in response to rising prices of certain goods.

Related: Is There a Less Painful Way to Fix Social Security?

What if I don’t get Social Security? Why should I care about any of this?

Even if it doesn’t affect you directly, Social Security and its annual adjustments are important to a huge portion of the U.S. population, meaning that they can carry some real economic significance. The COLA will affect benefits for more than 70 million people this year, which is more than one-fifth of the nation’s population. Nearly 60 million retirees, disabled workers, spouses and children collect Social Security benefits. The COLA will also affect benefits for around 4 million disabled veterans, 2.5 million federal retirees and their survivors and more than 8 million people who receive Supplemental Security Income. And a flat COLA actually has some surprising implications for Medicare beneficiaries.

Wait, what does this have to do with Medicare?

Social Security and Medicare are actually linked in a way that could result in a big jump in Medicare Part B premiums for some seniors unless Congress or the Department of Health and Human Services step in to prevent it.

Most Medicare beneficiaries pay their Part B premiums, currently $104.90 a month, out of their Social Security benefits. Those premiums are expected to jump next year, meaning Social Security recipients would see their checks get smaller — except that the so-called “hold harmless” provision in the Social Security law disallows an increase in Medicare premiums for 70 percent of Social Security recipients if their COLA is too small to cover the added cost. The rule prevents most people’s Social Security payments from falling from one year to the next.

It doesn’t apply to the remaining 30 percent of beneficiaries, though, meaning that they don’t have any protection from the rise in premiums. This group is made up of 3.1 million seniors with above-average incomes, the 2.8 million people who will be new to Medicare next year, and 1.6 million Medicare beneficiaries who don’t pay Part B through Social Security because they haven’t started receiving their retirement benefits yet. Troublingly, most of these people are lower-income Medicare beneficiaries who claim both Medicare and Medicaid.