Filibuster rules in the Senate may have changed – but the “hold” remains.

Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid and his Democratic colleagues last Thursday voted to change Senate rules to eliminate filibusters for most nominations by presidents. The historic move will allow federal judicial nominees and executive-office appointments to advance to confirmation votes by a simple majority of senators, instead of the 60-vote supermajority that’s been standard for nearly four decades. “It’s time to get the Senate working again,” said Reid.

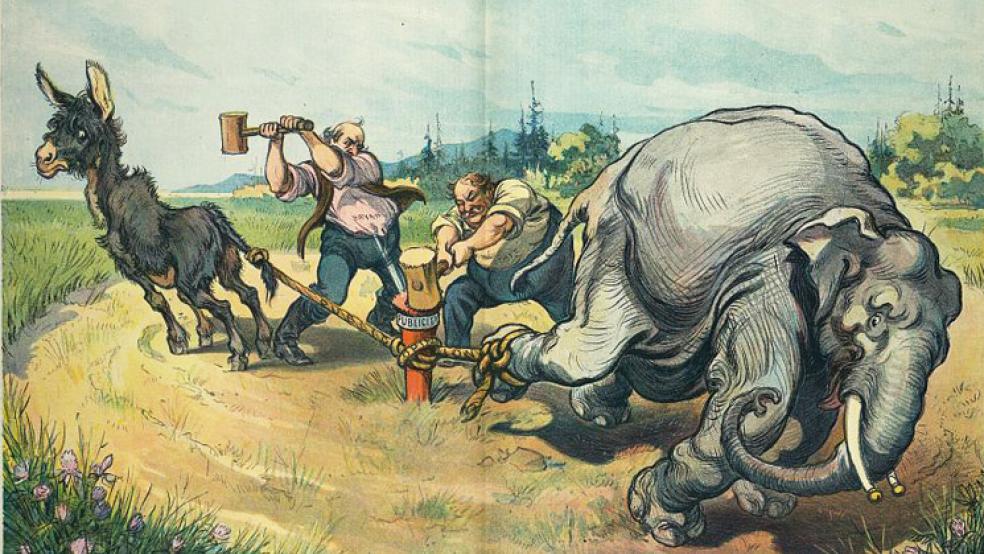

Related: GOP Plots Its Next Move against the Nuclear Option

But a mysterious and hard-to-quantify power still remains an option for individual senators of any party. They’re still able to postpone a judicial or executive branch nomination for any reason by using a “hold” – something Senator Mary Landrieu (D-LA) exploited three years ago.

In the fall of 2010, Landrieu announced she intended to block the confirmation of Jack Lew, President Obama’s choice at the time for new budget director, until the administration lifted a moratorium on deepwater oil drilling in the Gulf of Mexico.

Landrieu put a “hold” on Senate action on Lew’s nomination – a relatively obscure but potent form of filibuster – to block the nomination. Two months later, she lifted that hold but only after extracting the concessions she wanted.

In light of last week’s vote, Harry Reid and future majority leaders may be less inclined to grant hold requests, knowing they could almost always muster a simple majority to overcome any nomination stalling tactics. Because practically every bit of Senate business requires the unanimous consent of the members. A majority leader may be reluctant to make an enemy of any senator seeking to put off a confirmation vote – especially if that member could galvanize other members of his party to help obstruct Senate business.

“Holds are still there,” said Norman Ornstein, a congressional scholar at the conservative American Enterprise Institute. “What they did not do was fundamentally change the Senate. Everything that is done pretty much has to be done by unanimous consent, and if you don’t do it by unanimous consent, it’s still a relatively unwieldy [and time-consuming] process.”

A senior Democratic majority adviser agreed that while the vote late last week to curb the filibuster powers of the minority party may have weakened the efficacy of holds, the little known but frequently exercised privilege is still intact.

“A hold is an implicit filibuster,” explained the aide. “Its viability depends on the ability to back it up with an actual filibuster. The value of a hold continues, but it has been diminished.”

Related: Republicans Threaten to Use Yellen as Political Football

Interestingly enough, the practice of putting holds on legislation and nominations is not mentioned in the Senate rules, but it evolved over time as a cherished custom. For many decades, senators could secretly place holds on nominations, thwarting the president’s will without having to publicly own up to it.

Former Sen. Larry Craig, a Republican from Idaho, secretly put a hold on more than 200 Air Force promotions in June 2003, to pressure the Air Force to make good on what he contended was a commitment to station four new C-130 cargo planes with his home state’s Air National Guard.

The hold became a major controversy after it was disclosed by The Washington Post. Craig subsequently backed down under pressure from President George W. Bush, who was eager for the promotions to go through.

“The Senate has used a variety of tools over the years to get the attention of the executive branch,” Richard Baker, the former Senate historian, said at the time. “It's their prerogative to do it, whether it's a filibuster or a hold.”

In February 2010, Sen. Richard C. Shelby (R-AL) placed a blanket hold on about 70 of Obama’s nominations for senior federal posts in a dispute over whether to build a new Air Force aerial refueling tanker in his state and make Alabama the home of the FBI’s Terrorist Device Analytical Center.

“The purpose of placing numerous holds was to get the White House’s attention on two issues critical to our national security – the Air Force’s aerial refueling tanker acquisition and the FBI’s Terrorist Device Analytical Center,” Jonathan Graffeo, a Shelby spokesman, said at the time. Shelby lifted most of the holds after concluding he had gotten the administration’s attention.

Landrieu, the Louisiana senator, held up Lew’s nomination to head the Office of Management and Budget for two months before reaching a compromise with the Obama administration in November 2010. (Lew is now Obama’s Treasury secretary.)

Landrieu said at the time she was satisfied the Obama administration had sufficiently lifted its moratorium on deepwater oil drilling, which she argued was disastrous for the Gulf Coast economy. The drilling ban had been put in place following the BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill that April.

“I figured it would get their attention and I think it has,” Landrieu said.

Most recently, Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC) invoked this same obscure procedure by threatening to block Obama’s nomination of Janet Yellen as the new chairman of the Federal Reserve, Jeh Johnson to head the Department of Homeland Security and others.

Graham sought the holds in his long-running dispute with the administration over the release of information about the terrorist attack on a U.S. diplomatic mission in Benghazi, Libya, on Sept. 11, 2012.

After last week’s rule change essentially eliminated filibusters for most of the president’s nominations, a crestfallen Graham tweeted: “The hold I placed on many Obama nominees until Congress was able to speak with the #Benghazi survivors has been greatly eroded.”

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: