As policymakers in Washington continue to argue about the costs and benefits of raising the federal hourly minimum wage from the current level of $7.25 to the $10.10 recommended by President Obama, the actual amount of money a minimum wage worker takes home in a year is often, for one reason or another, obscured.

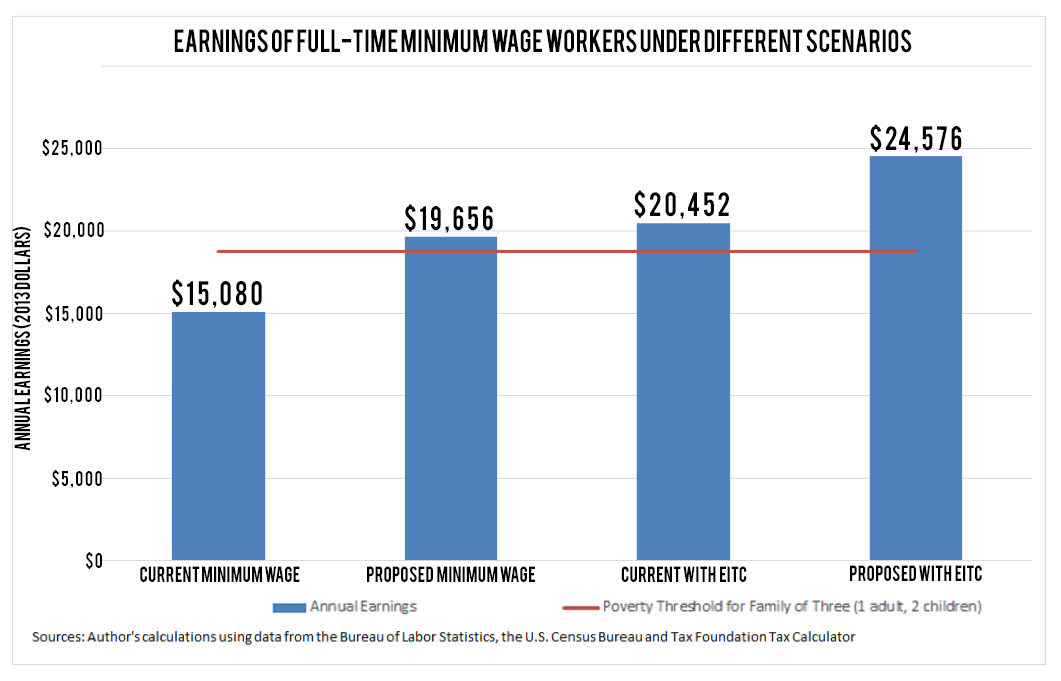

In testimony before the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions yesterday, Dr. Heather Boushey, executive director and chief economist of the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, provided a useful graph outlining just how much workers currently earn and how much of a boost to earnings they receive from the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC).

Today, a worker earning the minimum wage who works 40 hours per week, 52 weeks per year, with no days off, sick days, vacation, or other missed work, would earn $15,080. As the graph below shows, that leaves a family of three considerably below the federal poverty line. However, the EITC, which is designed to encourage work among low-wage employees, provides an additional 36 percent boost in overall income, pushing that family just above the poverty level.

Should Congress raise the minimum wage as the president has suggested — an increase of nearly 40 percent — the annual take-home pay of a minimum wage worker would jump to $19,656, leaving a family of three just above the poverty line even without the EITC. Because the EITC phases out as income increases, the boost to take-home income from a minimum wage worker making $10.10 per hour is more modest, at 25 percent.

Some who oppose the increase of the minimum wage on the grounds that it would reduce job creation argue that expanding the EITC is actually a better idea. Writing in The Washington Post earlier this year, economist Glenn Hubbard, former chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers in the George W. Bush administration, said that increasing the benefits to certain low-wage workers would "help counter poverty among the working poor." There is also some debate among economists over whether the EITC would be more effective if it were delivered as a regular paycheck supplement, rather than a lump sum at tax time.

Still, Boushey’s chart is a strong visual reminder of just what minimum wage workers earn, and how much of a federal benefit is needed to bring their income to a level that keeps them out of poverty.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times:

- Obama’s Overtime ‘Order’ Gets An Overreaction

- Why Dems Are More Worried Than Ever About November

- Employment Levels Normal, Except for Long-Term Jobless