The good news out of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York on Monday is that political polarization in Washington, D.C., appears to have little effect on the country’s economic growth. The bad news is that it correlates strongly with income inequality.

The study, by senior economist Rajashri Chakrabarti and research analyst Matt Mazewski tracked political polarization in Congress going back to the mid-1800s. To be clear, they were not tracking the distribution of seats in either house of Congress, but the ideological distance between the average Democrat and the average Republican, regardless of which party held the majority at any given time.

Related: The Biggest Policy Mistake of the Great Recession

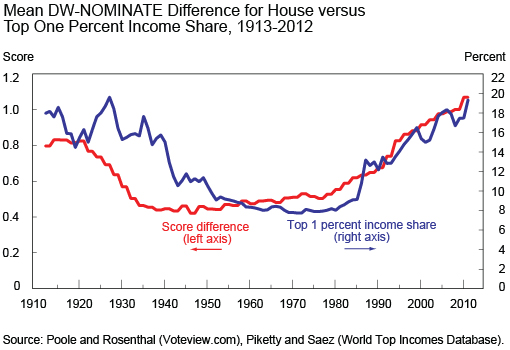

It will shock nobody to learn that polarization in Washington is at an all-time high. But what might be surprising is that it is not all that much higher than it was in the years leading up to the Great Depression. Polarization hit its lowest ebb in middle decades of the 20th century, and has been steadily increasing since the mid-1980s.

They also determined that the majority of the increase in polarization in recent decades has been due to the Republican Party shifting to the right.

“We can confirm that polarization has increased over the past thirty-five to forty years, and that it has done so in an asymmetric way, with Republicans moving further from the center than Democrats [on fiscal issues],” they write.

Income inequality, the authors find, tracks political polarization fairly closely, though with a lag of about five years. Interestingly, the correlation appears to be largely driven by the attitudes of Republican members of Congress, meaning that the further the GOP moves from the center, the more likely income inequality is to increase. Democrats have a much weaker impact, regardless of whether they move closer to or further away from the political center.

Related: For Pope Francis, Religious Visit Quickly Turns Political

The authors offer several possible explanations for their findings. One suggestion is that polarization leads to legislative gridlock, and leaves Congress unable to do away with outdated legislation that has begun to benefit the wealthy more than it was originally intended to.

Another possibility, they suggest, is that when the Congress shifts toward the right, the regulation of financial services firms tends to be weakened, which can lead to a surge in income for some of those already at the top of the distribution.

However, both explanations appear to be speculative at best, with no supporting data provided.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: