A disturbing new study from the Urban Institute reveals that one out of every 20 American adults on file with credit reporting agencies has at least one debt that is between 30 and 180 days past due, and that more than one in three has had a debt sent to a collections agency within the past seven years.

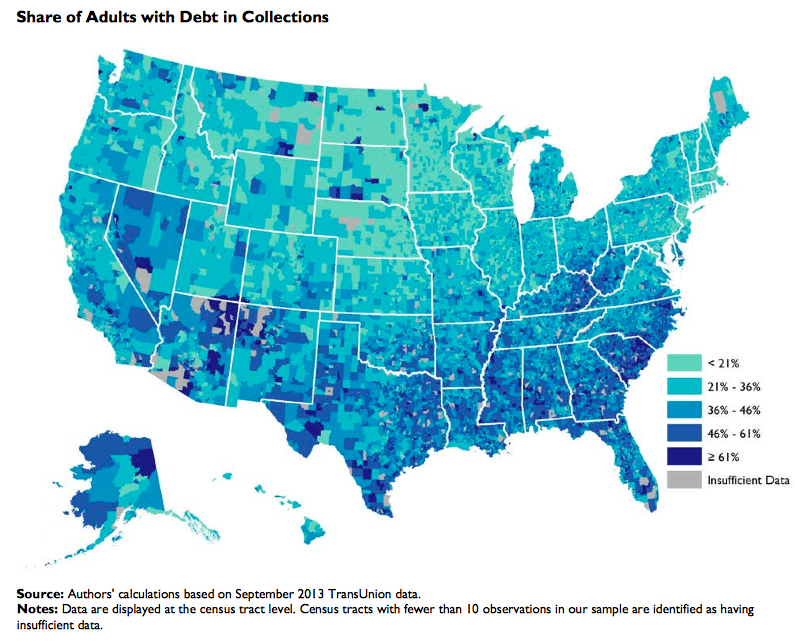

Lead author Caroline Ratcliffe, a senior fellow at the Urban Institute, and her team of co-authors analyzed seven million credit reports from the TransUnion credit bureau and found that while credit troubles are most common in the Deep South and in Southwestern states, delinquency is a problem almost everywhere in the country.

Related: Credit Score Change Could Set up Consumers to Fail

“They are stunning numbers,” Ratcliffe said. “Debt in collections is pervasive, and it threads through nearly all communities.”

The findings suggest one reason why the country’s recovery from the Great Recession has been so slow. Personal debt is a key factor that banks and other lenders take into account both when making decisions about whether to offer credit to a consumer in the first place and when deciding what interest rate to charge.

“The important part of it is that this debt can harm people’s credit score,” said Ratcliffe. “Outstanding debt can decrease access to credit and increase the cost. To the extent that it impacts people’s access to well-priced credit it can affect whether they will be able to buy a home or get that loan to start a business.”

The impact of widespread credit problems can also have an impact that goes beyond the opportunity to purchase a home or start a business.

Related: S&P – Income Inequality Threatens Long-Term Economic Growth

“Businesses base hiring decisions on credit reports,” she said, “It can impact whether people get an apartment.”

The study found that 5.3 percent of adults are currently between 30 and 180 days past due on at least one debt, and that the average amount of money they would need to bring their account back to current status is $2,258.

The reason why the number of people currently past due is so much lower than the number of people with debt in collections is the way the credit reporting system is structured. In general, a debt is classified as past due after it is 30 days late, and until it is 180 days late. Afterward, the creditor typically writes off the debt and sells it to a collections agency. Once this happens, credit bureaus classify the debt as being in collections, and it can remain on an individual’s credit report for seven years.

Related: Why High Debt Could Mean Financial Stability

That means it is possible for a consumer to have no “past due” accounts at any given time, but simultaneously have multiple accounts in collections.

Ratcliffe and her colleagues were able to break down their data to the Census tract level, and what they found is that credit problems are the worst in the “West South Central” states of Texas, Louisiana, Arkansas, and Oklahoma. On average, 7.5 percent of adults in that region are past due on at least one debt, and 43.6 percent have a debt in collections.

Louisiana was, by far, the state with the most individuals with past due accounts. The report found 8.7 percent of Louisianans were between 30 and 180 days past due on a debt. The next worst state, Texas, had only 7.6 percent of consumers past due.

Related: Student Debt Relief Scams on the Rise

However, neither Texas nor Louisiana was the worst when it came to debt in collections. On that score, Nevada led the pack with a remarkable 46.9 percent of consumers who had at least one debt sent to a collections agency. South Carolina ran second in that category at 46.2 percent.

Utah had the smallest percentage of past due debts, at 3.4 percent of the population, and North Dakota had the smallest percentage of adults with debts in collection at 19.1 percent.

Ratcliffe offers one word of advice to consumers considering applying for credit: Check your credit report beforehand.

While most of the delinquent debt reports are accurate, she said, some aren’t. Many consumers don’t even realize they have a debt in collections until they look at their credit file.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times