The Federal Reserve has had its foot on the gas for so long that the conventional wisdom says a tap of the brakes can’t be far away. But just when and how hard the Fed should hit those brakes is still the subject of furious debate. The right answer — what’s really best for the economy — depends in large part on how much “slack” there is in the labor market, and economists readily admit that’s a hard measure to gauge.

Since the Great Recession, the labor force participation rate — the percentage of the population gainfully employed or looking for work — has dropped significantly. Part of the reason is demographic, because the baby boom generation is hitting retirement age. As a result, labor force participation started declining before the recession and is projected to continue that decline for at least another decade. Demographic changes and other similar issues not specifically related to economic conditions are referred to as “structural” effects.

Related: Fed Watching – the Interest Rate Guessing Game Is Back in Style

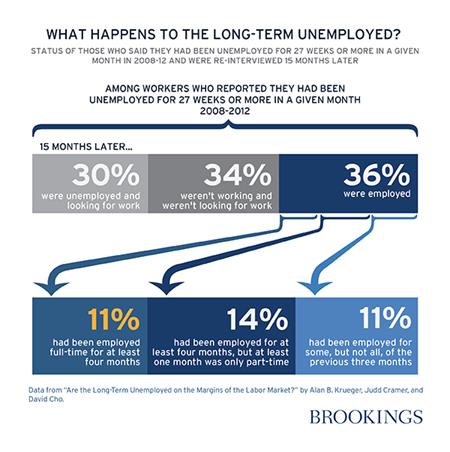

Part of the change clearly has to do with the economic cycle — “cyclical” effects. It hasn’t just been older Americans dropping out of the workforce; the percentage of men between ages 25 and 54 has fallen to multi-decade lows. The aftermath of the Great Recession saw extraordinarily high levels of long-term unemployment. Many of those who were unemployed for more than 27 months (the rough definition of “long-term” joblessness) became “discouraged” and left the labor force, which meant that they were no longer counted among the unemployed for purposes of official recordkeeping.

Economists are struggling to determine just how much of the decline in participation is structural and how much is cyclical — and it’s not a question with a clear answer. There is significant disagreement among economist about whether there is even a clear line to be drawn between cyclical and structural effects.

Now that the economy is creating hundreds of thousands of jobs per month, though, finding an answer is becoming a bit urgent because the Fed needs to try to calibrate its actions in a way that avoids two undesirable outcomes.

One is stimulating the economy past the capacity of the labor force to provide the needed workers, which would result in unacceptably high inflation. The other is hitting the brakes before the economy has reabsorbed all the workers who would like to return to the labor force. If that happens, we face the human cost of an unknown number of people left out of work as well as a hit to Gross Domestic Product, because the labor force is not being used to its full capacity.

Related: Why Employers Are in the Hiring Game Again

The question has created an active debate in the economic community. Fed Chair Janet Yellen has come down on the side of those who believe a substantial number of workers will return to the labor force if the economy creates sufficient demand for their services — meaning she thinks a large part of the problem remains cyclical. Others, including Princeton University economist Alan Krueger, the former head of President Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers, have suggested that a large percentage of discouraged workers won’t be coming back at all, for various reasons including age, the availability of social safety net benefits, and other factors that fall under the heading of structural issues.

A paper presented at the Brookings Institution last week by a group of Fed economists appeared to come down on Krueger’s side, finding that structural effects might account for the great majority of the decline in labor force participation. But even the presenters admitted that their findings were, in effect, one more data point in a very, very complicated discussion.

How the FOMC members weigh the existing evidence as they gather for a two-day meeting this week will be much on the minds of market participants. The Fed is set to wind down its “Quantitative Easing” program, which has involved buying huge amounts of Treasury securities and mortgage–backed securities, next month. By creating artificial demand for those bonds, the Fed kept the return on investment low, and increased the incentive for businesses and individuals to put their money into more productive investments.

Related: How Extended Unemployment Myths Hurt Millions of Americans

But the QE program was not the only way the Fed stepped on the gas. In fact, the QE program was only adopted after interest rates were driven to historically low levels. It was, at first, viewed as extremely aggressive.

While many expect interest rates to start rising as soon as mid-2015, the FOMC members’ conclusions about the levels of slack in the labor market are likely to be the single biggest driver — absent a wholly unexpected jump in the inflation rate — of their decision on interest rates.

At the moment, it seems there is little consensus about just how much slack remains.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times:

- 10 Worst States for Your Tax Dollars

- Businesses Consider Dumping Employee Health Coverage

- How Unemployment Myths Hurt Millions of Jobless Americans