If you've followed the market and the economy over the last few years, you've probably got a rough understanding that the Federal Reserve is propping up stocks. Maybe you're not sure exactly how it works, but the idea is just sort of out there.

Such is the benefit of holding short-term interest rates near 0 percent since 2008 and of growing the monetary base from $850 billion then to more than $4 trillion now.

Related: The Threat That Could Scar the Economy for Decades

Technically, the Fed isn't directly helping the stock market. It's buying long-term government bonds and mortgage securities. But by lowering the cost of credit for corporations, it's helped dump trillions into stocks as CEOs have leveraged up their balance sheet by issuing debt cheaply and using that money to repurchase their own shares.

The thing is, with the Fed's latest bond buying program on track to end next month and with corporations saddled with loads of debt, the dynamic is already slowing down. In other words, stocks are already starting to feel what it's like to lose the Fed's support. And it's set to get worse.

The practice of using debt to repurchase shares has become so widespread and aggressive — no wonder, since executive compensation is often tied to stock price and earnings per share metrics that benefit from reduced share counts — that it is believed to be limiting actual physical investment in plants and equipment.

This could be one of the reasons that both labor productivity and the capital expenditures component of GDP growth have been weak recently (private nonresidential fixed investment is growing at around a 7 percent to 8 percent rate vs. peaks of near 12 percent hit during the last two economic expansion).

So far, this dynamic has continued because of the Fed's ongoing purchases, the bond market's ongoing appetite for risk and the ability of corporate balance sheets to handle growing debt loads. Free cash flow and profitability are the key factors here.

Some of this is starting to change. The high-yield corporate bond market — or junk bonds — has been showing signs of weakness over the past week. The Barclays High Yield Bond SPDR (NYSE: JNK) tested below its 20-day moving average on Thursday for the first time since July.

If the weakness were to continue, it would limit the ability of companies to issue debt at low cost. Right now, there is a stampede to float debt after a summertime lull. Nearly $40 billion of high-grade debt was sold this past week, according to the The Wall Street Journal, the third-highest weekly total so far this year.

Overall, high-grade and junk-rated bond sales have already reached the $1 trillion issuance level for the year to date, the fastest pace on record (going back to the mid-1990s). This follows a strong performance last year. According to Andrew Lapthorne at Societe Generale, all this cheap debt has allowed corporations to be "the major net buyer of U.S. equity in recent years," with purchases totaling $500 billion in 2013.

Related: Commodity Prices, Bond Yields Send Warning Signals

With stock prices at all-time highs and the S&P 500 crossing the 2,000 level for the first time ever, these debt-fueled stock buybacks are growing increasingly expensive. And with the Fed's current bond purchase program expected to taper down to zero next month, given the strength of the economy and the steady pace of job creation, borrowing costs are likely to rise — further raising the total cost of these debt-fueled buybacks.

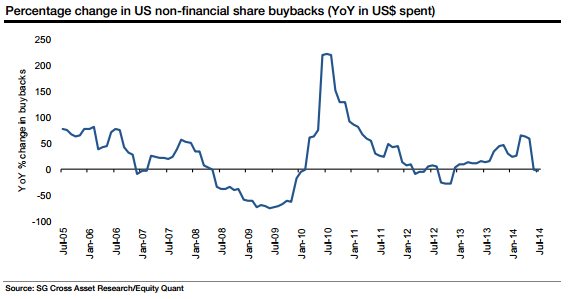

The chart above from Societe Generale shows, the combination of all this has resulted in a slowdown in the pace of share buybacks to levels not seen since late 2012. Further declines are likely, since without the Fed's bond buying "facilitating the extra debt, buybacks will have to be scaled back, undermining a key support to the equity bull market," according to Lapthorne.

At this point, we don't know how much of this drop is because of the Fed's tapering, or increasingly stretched corporate balance sheets, or simply folks realizing that this borrow-for-buybacks dynamic can't last forever. The more debt a company accrues, the more it's leveraged to the business cycle. In other words, any shift in revenue will have a larger and larger impact on net income because of the steady drag of fixed interest expenses.

According to Morgan Stanley, a large chunk of corporate debt will mature in the 2017-2018 timeframe. Should we get a recession between now and then and/or should interest rates rise significantly, corporate profits will get hit hard as free cash flow dries up and existing debt must be reissued at higher rates.

This behavior was also seen at the end of the last bull market, although the gap between buybacks and capital expenditures is more severe now than it was then. More simply, companies are neglecting real investment more than they did back in 2007.

An optimistic take is that when the Fed steps away, the stock market will cool its heels, but not collapse, as companies refocus on hiring, building and expanding. That'll be great news for the overall economy and America's workers. A pessimistic outlook is that, with the loss of a major source of support, stocks could drop in a way that hasn't been seen in years, potentially destabilizing the recovery.

What’s your take? Let us know in the comments section below.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: