If there was a sort of aesthetic justice in this world, certain nations – certain nice ones – should be exempt from the nasty bits of international life. Yes, perhaps America has to do Dad-things like hold irredentist Al-Qaeda members in Guantanamo Bay in a messy indeterminate status; but there’s no reason Canada has to watch. Canadians should be free to be semi-British and half-French and much more polite than their neighbors. But they’re not exempt.

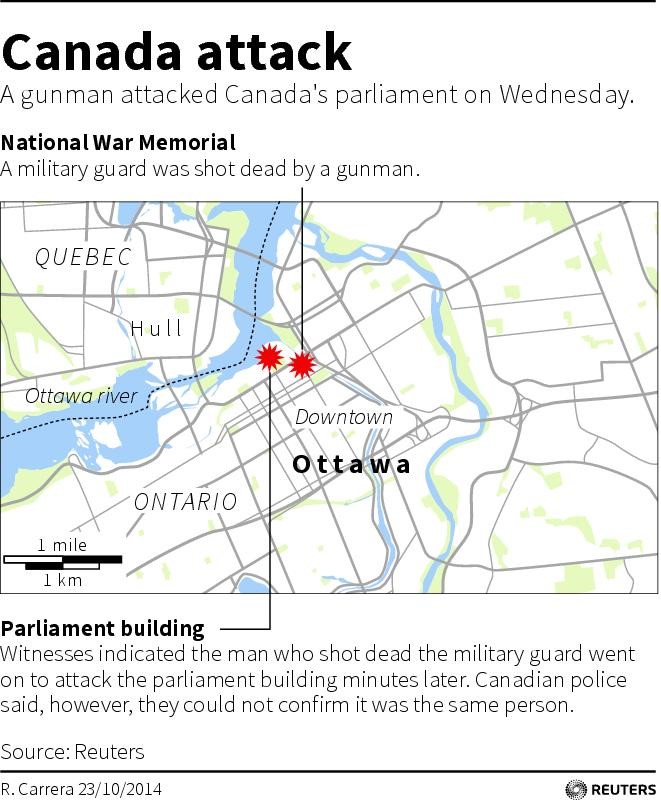

Michael Zehaf-Bibeau, an Islamic convert and radical, attacked multiple targets yesterday in Canada’s capital of Ottawa. He killed a soldier guarding the National War Memorial and then opened fire in the parliament buildings, before being killed by the legislature’s sergeant-at-arms. This attack came just days after two soldiers were run down by another Islamic convert in the parking lot of a shopping mall, and two weeks after Canada voted to join the war against ISIS.

Related: Canada’s Harper Pledges Tougher Security Laws After Attack

It’s almost unfair that this happened to Canada. Among the Anglophone offspring of mother Britain, Canada always seemed like the conciliatory middle child, pouring diligently over its homework en route to a stable, upper-middle-class professional life. Perhaps as a pharmacist. America was the heir to the family empire, playing a little rough by dreaming big. And Australia was the youngest, the gray sheep, stone-drunk and scrapping in bars with Prince Harry until both were given ultimatums to join the forces or else.

Pharmacists should never, ever experience terrorism. But we forget that Canadian troops have been at war alongside American troops since the Afghan war started in 2001. I knew several of them when I was stationed there with the U.S. Army, and they struck me as highly professional. And cheerful – second only perhaps to the Danes, the Canadians were the cheeriest troops I’ve ever met. But they were quite clearly allies who fought, like the other Anglosphere nations.

They fought in Kandahar, where the war was especially bloody, as well as elsewhere in the country. Canada’s Globe and Mail newspaper estimates that 40,000 Canadians served in Afghanistan: 158 died and over 2,000 were wounded.

They are thus no strangers to war and conflict. But they were strangers – mercifully – to the sort of large-scale terrorism that has hit Britain, Spain, Russia, Israel, India, and the United States. Not any more. And now like those nations, they face a choice: if the Ottawa attacks do turn out to be the work of ISIS or Islamic militants: what now? What do we do, and what do we change?

Related: Canada Police Talked to Militant Suspect, Couldn’t Stop Attack

Every attacked nation has had to answer that question for itself. After September 11th, the United States filled with can-do Gunga Din valor and vowed the sort of all-encompassing policy solution that Americans love. This thing, by God, was going to be fixed.

The British, after the devastating 2005 Tube bombings in London, took a different tack. No matter how much Tony Blair told them that it was not caused by Iraq, the electorate thought otherwise. The British stuck it out: but that bombing, on top of the failure to find Saddam’s nuclear program, contributed to crushing disapproval of British involvement in the war and limited David Cameron’s ability later to help the U.S. in Syria.

Spain was blunter, pulling out of Iraq in 2004 almost immediately after its train bombings in March. The public turned decisively against Prime Minister Jose Aznar, whose support for the war was seen to have caused the attacks. He was defeated shortly thereafter.

Related: ISIS Terrorists Learn to Fly in Iraqi Jets

By contrast, the terrorist attacks against a Moscow theater in 2002 and a Beslan school in 2004 didn’t seem to phase Russia that much. The Russians weren’t doing anything that fixable, for one thing: their main offense against the global Islamist zeitgeist had been Chechnya, and – Putin was very clear about this – they preferred to keep it. India and Israel had experienced multiple terrorist attacks as well since 9/11, and both had similarly limited reactions. India and Israel were stuck with their sins – neither Kashmir nor the Palestinian territories were going anywhere – and it wasn’t clear there would be any relief even if they did.

Russia and India are not right and Britain and Spain wrong: they simply reflected different costs and benefits. Terrorism is unfortunately effective at raising the costs of policy in the eyes of the public. Here’s when it’s not always effective:

- When a certain goal is vital to the state, like security in Gaza, terrorism usually doesn’t work.

- When it’s not vital, like the second Iraq war…well, things can turn out differently.

Prime Minister Stephen Harper said they would not be intimidated by these attacks. They will not change course. On October 7th, the Canadian parliament voted to join the coalition against ISIS, including launching airstrikes against militants and training security forces on the ground. But it was a fairly narrow vote, decided by only 20-odd MPs, as befits a policy that’s not necessarily vital to state interests. The question now becomes, how will Canada react to the terror in Ottawa?

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: