In response to a stronger-than-expected February jobs report, stocks careened lower on Friday for the first serious selloff since January. The Dow Jones Industrial Average, the S&P 500, the Nasdaq and the Russell 2000 all lost between 1.1 percent and 1.5 percent. In a flash, the Dow was brought back to the level it was at about a month ago.

The unemployment rate is now down to 5.5 percent, at the upper end of the Fed's estimate for full employment. Payrolls expanded 295,000, well above the 230,000 economists had expected, making the current job market expansion the most consistent run since 1995. Total employment is up by 11.5 million jobs from the post-recession low and by 2.8 million from the December 2007 pre-recession peak. Wage growth was a little soft, with average hourly earnings increasing 0.1 percent month-over-month, a slight slowdown from January's 0.5 percent growth rate.

But the overall message is clear: Good news is apparently bad news again. What's good for middle-class Americans isn't such great news for the stock market.

Related: Why the ‘Smart Money’ Is Bailing Out of the Bull Market

For one thing, the latest jobs data greatly increase the odds that the Federal Reserve will remove the "patient" language from its March 18 policy statement and raises interest rates in June for the first time since 2006.

Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond President Jeffrey Lacker said Friday that the job market has moved at a faster pace than expected and that June should be the leading candidate for rate liftoff. He noted that the Fed didn't need to wait for wage inflation to hit before raising rates. Outgoing Dallas Fed President Richard Fisher, in his final speech, said the job market is at capacity, or full employment, and that wage pressure will eventually rise.

Given how deeply dependent the market has become on the flow of cheap money from the Fed, it's not surprising that stock bulls are suffering some discomfort, especially since the end of the QE1 and QE2 bond buying programs in 2010 and 2011 resulted in large selloffs. QE3 ended late last year, and we've yet to see a major market drop. This time, the end of the bond buying will be mixed with an outright increase in the cost of money as the Fed prepares to start its first tightening cycle since 2004.

Related: The Fed’s Patience Is About to Run Out

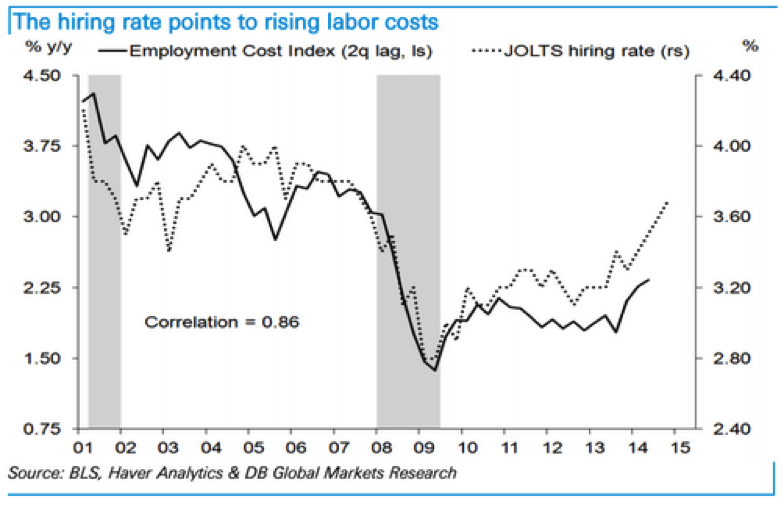

Two, with the economy at or very near full employment we're likely on the cusp of a surge of wage inflation. Deutsche Bank economist Joseph LaVorgna believes that based on the rise in the hiring rate — from the government's Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey — wages should climb higher later this year. A similar prediction is based on the rise in the number of workers feeling confident enough to quit.

But look at LaVorgna’s chart above and notice how he is measuring wages: In terms of the cost of employment to businesses. While Americans will enjoy higher wages, companies will suffer higher labor expenses in a big way for the first time since the recession started. That will pressure profit margins and earnings growth, which as I've discussed recently, looks set to roll over sharply.

Put simply: Higher wages and fresh record highs in corporate profits are not compatible with each other. Periods of strong wage growth have, historically, been associated with a collapse in profit growth.

Finally, the combination of higher wages, higher interest rates and lower profitability will be a toxic brew that threatens to undermine the other big dynamic that's been pushing stocks higher in recent years: Debt-funded corporate buybacks.

According to TrimTabs data, buyback announcements soared to a record $104.3 billion in February and averaged a robust $3.4 billion per day in the first two months of the year. This surpasses the prior high of $99.8 billion set in July 2006. Davd Santschi, chief executive officer at TrimTabs, notes that "extremely low corporate borrowing costs" are one of the key factors driving the buyback boom.

That's at risk as rates push higher. Already, fewer companies are announcing buybacks: There were 123 purchase announcements last month, significantly below the record 196 in August 2011.

As interest rates and labor costs rise, and earnings growth stagnates, it will become less and less attractive to do buybacks. That, as a result, will remove from the market a major source of buying demand. On Friday, the 10-year Treasury yield surged to 2.2 percent — up from a low of 1.7 percent in February — as bond traders prepared for rate hikes. Corporate yields should drift higher in sympathy, making debt issuance to fund buybacks less appealing.

Yardeni suggests that such a squeeze could take a long time to play out, as corporations are flush with cash, other central banks are easing (21 global rate cuts so far this year and the European Central Bank is about to start its own bond buying program) and the Fed is likely to take its time on rate hikes.

Still, with valuations and bullish sentiment both extended, the realization that a tighter job market threatens many of the core foundations of the post-2009 bull market should be enough to give investors pause in the weeks and months to come — especially if the Fed signals a move on rates later this month.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: