The issue of inequality has been a recurring theme in U.S. politics since the financial crisis and Great Recession of the last decade spawned the Occupy movement, which gained broad attention by, in part, highlighting the vast disparity between the wealthiest 1 percent of Americans and the other 99 percent.

The question of whether the distribution of wealth and income in the U.S. is economically or morally optimal keeps resurfacing. In the 2012 election, Mitt Romney unwillingly called attention to it with his comments about the “47 percent” of Americans who, he said, are “dependent on government.” President Obama, in a late 2013 speech, called inequality “the defining challenge of our time.”

Related: Chris Christie Brings the Pain

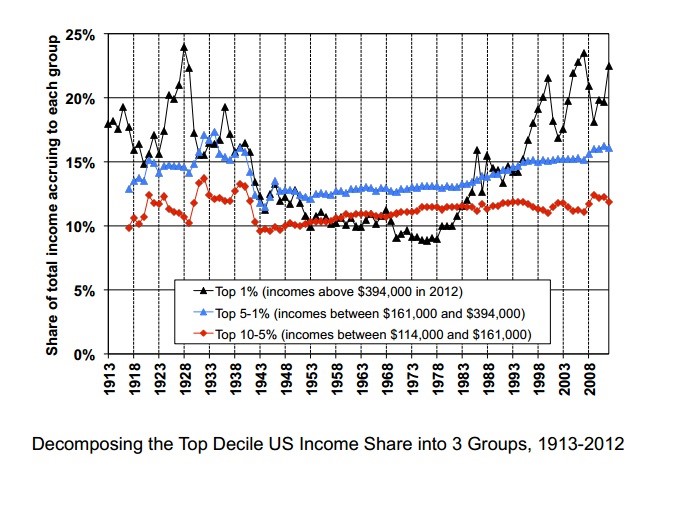

On its face, it’s difficult for many to stomach the fact that an enormous share of income in the United States goes to a very small portion of the population, while the majority of the population is left to share, by some measures, less than half of the nation’s wealth.

But new research from Scott Winship, a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, asks readers to set aside concerns about the inequality of wealth distribution in the U.S., and ask whether the promise of outsized rewards to highly successful people might actually benefit everyone – even those near the bottom of the income distribution.

“Across the developed world, countries with more inequality tend to have, if anything, higher living standards,” he writes. “The exception is that countries with higher income concentration tend to have poorer low-income populations.

“However, when changes in income concentration and living standards are considered across countries…larger increases in inequality correspond with sharper rises in living standards for the middle class and the poor alike.”

Related: Why Have Policymakers Abandoned the Working Class?

This gets to Winship’s main point, which is that concentrating on the perception of injustice in the distribution of income may distract from the possibility that the potential to earn vast sums of money might motivate some people to create new products or businesses or to innovate in existing fields in a way that ultimately benefits everyone by improving the economy and raising living standards.

Source: AEI

“In developed nations, greater inequality tends to accompany stronger economic growth,” he writes. “This stronger growth may explain how it is that when the top gets a bigger share of the economic pie, the amount of pie received by the middle class and the poor is nevertheless greater than it otherwise would have been. Greater inequality can increase the size of the pie.”

He illustrates his point with a reference to the Gini Coefficient, a measure economists use to denote the distribution of income across a society. With a 100 point scale, a 0 on the Gini Coefficient denoted perfect equality and 100 complete inequality (all income goes to one individual.)

Manhattan, he points out, with its vast wealth in some neighborhoods and pockets of poverty in others, has a Gini coefficient roughly equal to that of South Africa.

Related: Whay’s the Best Way to Overcome Rising Income Inequality

“That Manhattan and South Africa possess similar Gini coefficients does not imply that one ought to be indifferent between living in the two places,” he writes. “Nor does it imply that reducing Manhattan’s Gini would improve the living standards of its poor and middle-class residents. It is entirely possible, in fact, that lowering South Africa’s Gini would benefit most South Africans while lowering Manhattan’s would have the opposite effect on Manhattanites.”

Winship’s analysis is open to attack on a couple of fronts. First, as he points out himself, if an individual values equality for its own sake – even above maximizing overall societal wellbeing, then an argument that goes something like, “Look on the bright side. You could live in Uganda” won’t carry much weight.

And his concluding point is likely to raise the hackles of anybody with a large amount of sympathy for the movement to reduce inequality in the U.S.

“Rather than being the defining challenge of our time, as many observers believe, income inequality may be a distraction from the goal of raising living standards among the poor and the middle class, Winship writes. “The analyses in this paper suggest that efforts to reduce inequality are more likely to damage living standards than to improve them.”

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times