|

The inflation outlook is taking a new twist. So far the story has been dominated by surging prices for gasoline and food. Not to worry, many economists said, core inflation—which excludes the volatile energy and food sectors—was tame. Not anymore. Now core inflation is picking up, adding new pressure on household budgets and complicating the Federal Reserve’s efforts to balance its twin goals of containing inflation and reducing unemployment.

When economists talk about core inflation, most people roll their eyes. That’s OK, they say, as long as you don’t eat or drive. The higher cost of gasoline was the chief factor in the first-half slowdown in consumer spending, and the recent drop in oil and gas prices, accelerated by the release of 60 million barrels of oil from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve last week, will give spending a lift in the second half. But economists say these sharp swings temporarily drive the overall inflation rate up and down without affecting other prices, so core inflation gives a better read of the broader underlying trend. The Fed pays close attention to core inflation in setting monetary policy.

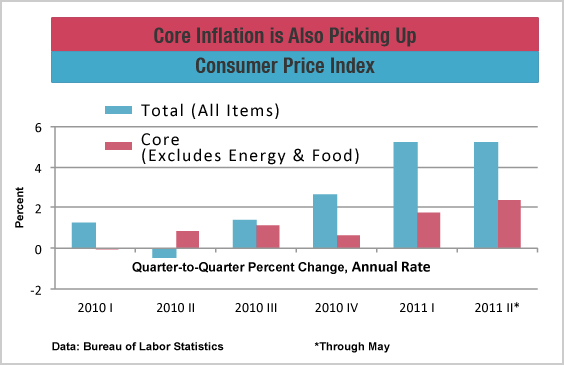

That reading looks increasingly worrisome. The core consumer price index posted a month-to-month rise of 0.3 percent in May, the largest since May 2006. The standard 12-month inflation rate for the core index, 1.5 percent in May, remains tame, compared to the 3.6 percent rate for the overall CPI. However, the 12-month rate has more than doubled from 0.6 percent in October, just before the Fed began QE2, its second round of quantitative easing involving purchases of Treasury securities. In the first five months of 2011, the annual rate of core inflation is an even faster 2.4 percent, with the pace picking up in each quarter.

The Fed launched QE2 when core inflation was falling toward zero, in an attempt to avoid a debilitating round of Japanese-style deflation. But the cost may have been a broad pickup in inflation that could force the Fed to begin pushing up interest rates sooner than many analysts expect. For the first time in more than a year, Fed policymakers in their statement following their Jun. 22 meeting, did not mention underlying inflation, completely removing a comment from the April statement that said underlying inflation was subdued. “Policymakers may no longer be drawing much comfort from the behavior of core inflation,” says Barclays Capital economist Dean Maki.

It’s not just the core CPI. Other core inflation measures, including the Fed’s preferred price index for personal consumption expenditures are also are picking up. J.P. Morgan economist Michael Feroli points to other less publicized inflation gauges, such as the Cleveland Fed’s median price index, which strips away items with very large up and down movements, and an index at the Atlanta Fed, which looks only at prices that change very infrequently. “All these measures have picked up this year,” Feroli says. They suggest that price pressures, while still relatively tame, are nonetheless broadening.

Some of this year’s acceleration is temporary, especially new autos, where prices so far this year are increasing at an 8.4 percent annual rate, reflecting both strong demand and shortages following the earthquake and tsunami in Japan. Airfares are rising at a 13.1 percent clip, at least partly reflecting costlier jet fuel.

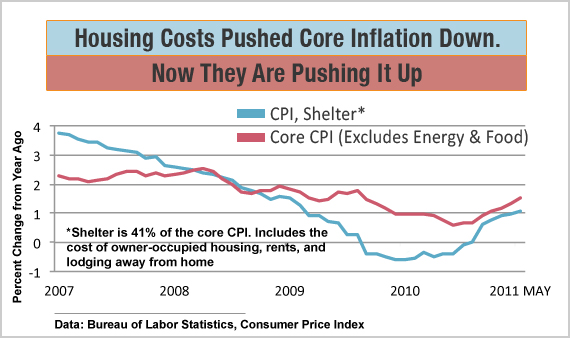

But at the same time, the basic cost of housing, called “shelter” in the CPI, is also rising faster. Shelter costs include owner-occupied housing, rents, and lodging away from home, and account for an outsized 41 percent of the core CPI. Outside of properties in foreclosure or short sales, home prices are rising, as Fed Chairman Bernanke noted at his Jun. 22 press conference. Inflation is also picking up for household furnishings, apparel, and recreation, none of which have much direct exposure to costlier fuels or supply disruptions. The number of small businesses saying they are raising prices has increased significantly over the past year, according to the National Federation of Independent Business.

If the Fed and many private-sector economists are right about the temporary nature of the first half slowdown in economic growth, the upward pressure on prices outside of energy and food will not abate in the second half, even as falling energy prices push overall inflation lower. Despite Wall Street’s sharp negative reaction to the Fed’s downgrade of its growth outlook last Wednesday, that same forecast implies a considerable pickup in the second half of 2011. If, as widely expected, economic growth comes in at about 2 percent for both the first and second quarters, the Fed’s projection of 2.7-to-2.9 percent for the full year would imply solid growth in the 3.4-to-3.8 percent range during the second half.

Several factors that depressed first-half growth are already turning around. Data and surveys show a strong V-shaped rebound in Japanese production, which should mitigate supply-chain disruptions, especially in U.S. auto output. Morgan Stanley economist David Greenlaw estimates that falling auto production subtracted 0.8 percentage points from second-quarter GDP growth, and that a rise in auto output aimed at rebuilding depressed inventories would add about 1.5 points to third-quarter growth. Plus, the drop in oil and gas prices will boost household buying power, and business outlays are likely to rise as companies rush to take advantage of tax breaks that accelerate depreciation allowances before the year-end expiration.

Most economists will say it’s very difficult to see a sustained rise in inflation amid so much idle production capacity, especially so many idle workers. However, given that many jobs may be gone forever and that more production has been shifted overseas, we really don’t know how much spare capacity there is in the economy. “While it is almost certainly quite large,” says UBS economist Kevin Cummins, “it has not been large enough to prevent core inflation from rising.”

Related Links:

Inflation Comes in Small Packages (The Fiscal Times)

Inflation Fears Rattle a Reeling Market (The Fiscal Times)

Inflation Ahead? The Fed May Raise Interest Rates (The Fiscal Times)