Long-term interest rates are rising again this week as bond traders front-run the Federal Reserve and look for a bounce back in inflation and "real" rates, a reflection of better economic fundamentals.

In early February, the yield on 10-year Treasuries was below 1.7 percent. On Tuesday, it tested above the 2.3 percent level, where it was back in November. Last week, yields spiked to levels not seen since October.

Related: 7 Quirky Economic Indicators – from Dogs to Guns

We appear to be in the midst of the first persistent rise in borrowing costs since the Fed ended its QE3 bond buying stimulus program last year. The fixed-income market is finally sniffing out a rebound in both prices and economic growth. It remains to be seen if this upward momentum will survive the Fed's short-term rate liftoff — the first such move since 2006 — expected sometime later this year.

Based on their recent comments, Fed officials are also coming around to the realization the labor market is nearing full employment, undermining any justification for holding interest rates near historic lows. San Francisco Fed President John Williams admitted earlier this week that the unemployment rate is nearing its natural rate — the threshold before wage inflation really starts kicking in as businesses fight for qualified applicants. Williams also noted that it would be safer for the Fed to start raising rates earlier and more gradually than wait too long and have to raise them drastically to stay ahead of inflation. And besides, the Fed's ability to delay rate hikes is more limited now in his opinion.

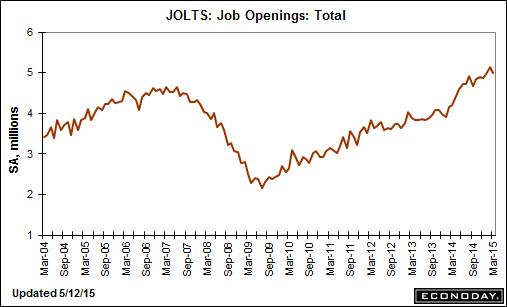

While job openings dropped slightly last month, the quit rate rose to 2 percent, and 2.2 percen within the private sector. This is an important measure of worker confidence that Fed officials, including Chair Janet Yellen, watch closely.

The rebound in the quit rate suggests the balance of power in the labor market is finally shifting from employers to employees; a leading indicator that wages, a powerful contributor to overall inflation (and thus, long-term interest rates), are about to get a big lift.

Related: The Pain the Job Numbers Don’t Show

Another dynamic coming into play is that the job market seems to be getting more efficient at matching workers to job openings. In the immediate aftermath of the recession, structural frictions manifested themselves. Perhaps hiring managers were spoiled by choice and got too picky. Or maybe negative home equity kept the right workers from relocating to where they were needed. Or maybe the slow process of worker retraining into areas of new demand was just getting started.

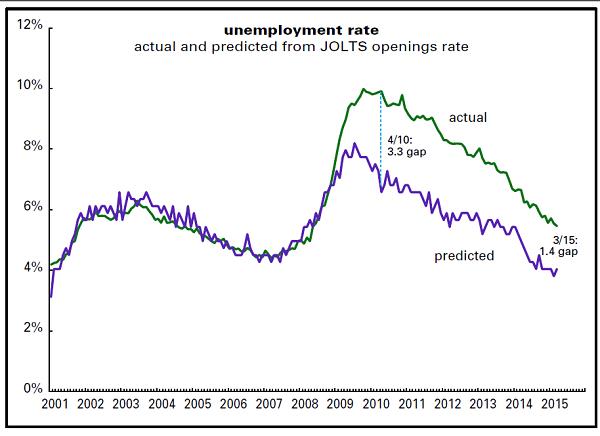

Whatever the cause, it's ending now. This can be seen in the chart below from Philippa Dunne of The Liscio Report, an independent research newsletter, which compares the actual unemployment rate to a model prediction based on the Job Opening and Labor Turnover Survey. Four years ago, the gap was 3.3 percent. Now it has fallen to 1.4 percent.

To simplify, just imagine that the pool of available workers is suddenly being drained at a faster rate. Like the drain pump just doubled in speed.

Related: The Job Market May Be Tighter Than It Looks

You don't need a degree in economics to take a guess at what this means: A rebound in consumer spending and a lift in retail sales. With consumers still responsible for the largest share of U.S. GDP, that means shoppers are about to overcome the drag from corporations get hit by the energy price pullback and the dollar's drag on foreign earnings. Consumers can lift economic growth through the rest of the year.

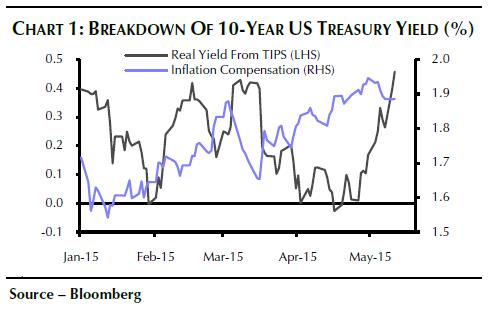

But don't just take my word for it. The bond market is already pricing all this in. According to Capital Economics, the lift in long-term interest rates in late April was initially driven by a rise in inflation expectations no doubt connected to the rebound in crude oil from a low of $42.41 a barrel in March to above $60 a barrel now — an increase of more than 40 percent.

Now, the rise in long-term interest rates (and thus, the price weakness of long-term Treasury bonds) is being driven by a big increase in economic growth expectations. This is derived from the inflation-adjusted yield on Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS). These rates are supposed to reflect the return TIPS holders receive in response to the underlying cost of capital set by the economy's growth rate.

Unless the Fed acts on rates soon — and despite the risk of destabilizing financial markets grown addicted to nearly seven years of rock bottom interest rates — it could fall behind the bond market and risk exacerbating the rise in long-term yields by further boosting inflation expectations.

It'll need to look past the weak March payroll report and acknowledge that years of ultra-aggressive policy stimulus have finally brought the job market back to health when it ends its next two-day policy meeting on June 17.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: