It’s essentially a coin flip. That’s how J.P. Morgan economist Michael Feroli describes the "hike/no hike" decision facing the Federal Reserve this week. The economic data "present a clear case for the Fed to begin the normalization process," Feroli says, while "recent financial market turbulence complicates the decision."

The uncertainty explains why the big traders were on the sidelines Monday: According to Nanex data, S&P 500 futures set a new record low average trade size. Fewer than 800 million shares traded hands on the NYSE floor vs. a 20-day average of 984 million. The Dow Jones Industrial Average has traded into a narrowing multi-week pennant formation as Wall Street goes into hibernation out of fear of a monetary policy winter.

Related: The Stock Market’s Fed Fever Is Only Going to Get Worse

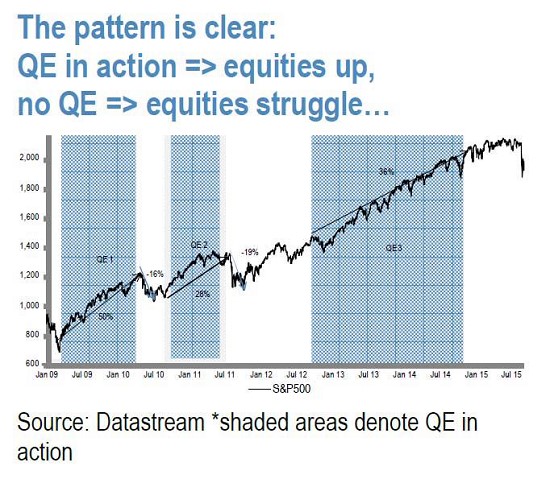

This should be no surprise: As the chart below from Citigroup shows, this bull market has been built in stages on the foundations of the Fed's now expired bond buying or "quantitative easing" stimulus programs. Faced with the prospect of the first monetary tightening since 2006, everyone is starting to realize just how unwieldy the Fed's influence has become, how intractable its decision this week is and how painful the consequences of a policy mistake could be.

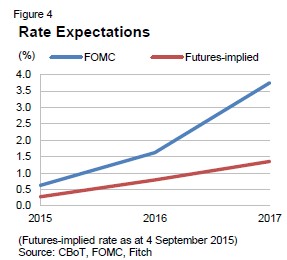

The futures market continues to believe that the near-0 percent interest rate policy will be maintained given market turmoil in August and vulnerabilities in China and elsewhere.

Current pricing puts the odds of a September rate hike at less than 30 percent. Yet by a slim margin a group of economists polled by Reuters believes a rate hike will happen this week for the first time since 2006. Fed officials themselves maintain a much more aggressive outlook on the pace and timing of rate normalization, opening a massive expectations gap between traders, economists and policymakers.

Related: What the U.S. Must Do to Avoid Another Financial Crisis

Traders just can't bring themselves to believe the greatest experiment in cheap money in history is about to end — but have begun battening down the hatches anyway. According to Lipper, investors redeemed more than $16 billion from equity mutual funds and ETFs through the end of last week. That brings the three-week total to a net outflow of $30 billion, a big number in anyone's book. Over the last 10 years this level of selling in a three-week period has only been seen two other times: In February 2008 (during the post-Obama inauguration meltdown) and August 2011 (during the fiscal standoff and credit downgrade panic).

In August, there were 13 consecutive sessions without a single investment-grade bond issued, the longest drought since the financial crisis. And it's been nearly a month since an IPO has been launched. That hasn't happened since August 2014.

It's clear the Fed is trapped. Especially since the global credit overhang — the side effect of the world's addiction to all the monetary morphine unleashed since 2008 — has only grown more dangerous.

Related: How Millenials Could Damage the U.S. Economy

Bank of America Merrill Lynch economist Michael Hanson believes a rate hike is the most likely outcome of a close call when Fed officials wrap up their meeting on Thursday because of the undeniable cumulative improvement in the economy and job market. Second quarter U.S. GDP growth is set to be upwardly revised to a 4-plus percent rate. And the unemployment rate has already fallen near the Fed's own estimate of full employment — a level, at 5.1 percent, officials didn't expect to reach until the end of 2016.

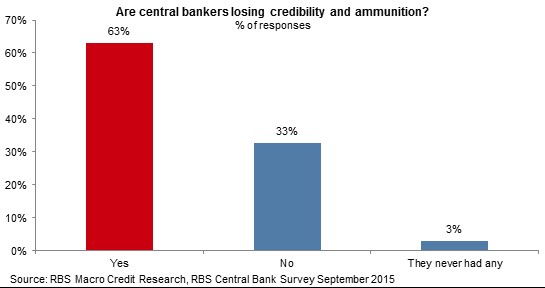

There is also the risk that if the Fed delayed it would lose credibility as a "data-dependent" institution that will, if needed, lean against speculative excess. Remember: This entire easing cycle was a response to the housing boom and credit binge of the mid-2000s caused by the Fed's mistreatment of the disinflationary forces of China's industrialization.

Credit analysts at Fitch and economists at the Bank for International Settlements this week became the latest to sound the alarm about the consequences of rate liftoff by the Fed. Fitch calculates that upwards of $7.5 trillion of emerging market debt — up from $2.8 trillion since the financial crisis — is vulnerable to a rise in U.S. rates of the type Fed officials themselves are predicting and market participants are ignoring.

Related: The Clearest Sign That the Job Market Hasn’t Really Recovered

The BIS calculates that every 1.0 percent move in U.S. interest rates will result in a 0.4 percent rise in EM rates, creating the conditions for a credit squeeze and a surge in defaults at a time when policymakers in Beijing and elsewhere are already scrambling to manage the impact of pinched corporate profits, slow trade and cratering commodities prices. A post-hike surge in the U.S. dollar would worsen this dynamic.

A "no hike" decision, explained away with appeals to still-low inflation and recent market turmoil, would buy some time and would surely be celebrated by investors. But with monetary measures running hot — the narrow M1 measure of the monetary base is growing at an 8.4 percent clip — inflation is a looming problem that will eventually force the Fed's hand as labor market slack diminishes.

In short: Whether it happens this week or later on, the liftoff in U.S. interest rates is coming. Markets — and the world — may not be ready yet.